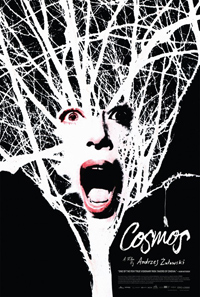

The Fault in Our Stars: Zulawski’s Uncompromised Return a Dark Hearted Farce

Throughout a filmography that’s spanned five decades, including two short films and now, thirteen features, Polish provocateur Andrzej Zulawski remains fascinated with a certain inescapable madness lurking beneath the superficialities of language and social custom. At times, his cinema seems to grapple with portraits of existence scrubbed free from comfortable veneers. His first feature following a fifteen year hiatus from filmmaking, Cosmos finds the 75-year-old auteur in top form, grappling with the challenge of adapting the last novel by celebrated Polish author Witold Gombrowicz. Described as an existential thriller, this fast paced, quick-witted examination of miscommunication and self-fulfilling prophecies is rather more a philosophical black comedy, stamped with Zulawski’s flair for dips into the well of emotional hysteria and off-putting human behavior. Though not as extreme as some of the iconic cult classics Zulawski has been worshipped for, such as 1981’s Possession, he’s lost none of his power to compel in this beautifully detailed and enigmatic return.

Throughout a filmography that’s spanned five decades, including two short films and now, thirteen features, Polish provocateur Andrzej Zulawski remains fascinated with a certain inescapable madness lurking beneath the superficialities of language and social custom. At times, his cinema seems to grapple with portraits of existence scrubbed free from comfortable veneers. His first feature following a fifteen year hiatus from filmmaking, Cosmos finds the 75-year-old auteur in top form, grappling with the challenge of adapting the last novel by celebrated Polish author Witold Gombrowicz. Described as an existential thriller, this fast paced, quick-witted examination of miscommunication and self-fulfilling prophecies is rather more a philosophical black comedy, stamped with Zulawski’s flair for dips into the well of emotional hysteria and off-putting human behavior. Though not as extreme as some of the iconic cult classics Zulawski has been worshipped for, such as 1981’s Possession, he’s lost none of his power to compel in this beautifully detailed and enigmatic return.

Troubled law student Witold (Jonathan Genet) arrives in an isolated Portuguese village, babbling to himself before he runs into a hanged sparrow. Without thinking, he grabs the dead bird, immediately regretting his instinct. Moments later, he runs into Fuchs (Johan Libereau), just leaving the hotel they both have reservations at which apparently has been overbooked. Luckily, a nearby residence has recently opened its door to lodgers out of economic need, run by orange maned Madame Woytis (Sabine Azema) and her peculiar husband Leon (Jean-Francois Balmer). The Madame’s daughter from her first marriage, Lena (Veronica Guerra) and her husband are also part of the semi-permanent residents, while the maid Catherette (Clementine Pons) sports a noticeable blight on her upper lip from a tragic car accident, which has the young men fascinated. Initially, they believe Catherette responsible for the mystery of the hanging sparrow. However, a series of surreal signs and symbols lead them to suspect other members of the very strange Woytis residence.

Winning Zulawski a Best Director award following its premiere at the 2015 Locarno Film Festival, this highly manicured and purposefully puzzling film is (hopefully) an indication of other productions to come. It is the third feature adaptation of Gombrowicz, an author largely celebrated in his native country, but whose purported playful experimentation with notions of language have prevented successful translations.

The first cinematic adaptation was Jerzy Skolimowski’s 1991 film 30 Door Key (aka Ferdyduke), which was followed by a seventeen year absence in filmmaking from that Polish auteur (filmed in English, it relates the story of a young man increasingly infantilized by his surroundings during WWII, and stars Crispin Glover as an antagonistic student). However, Zulawski’s handling of the material, and the inclusion of Sabine Azema, wife and frequent collaborator of Nouvelle Vague alum Alain Resnais, makes this chatty head-trip feel like one of Resnais’ adaptations of playwright Alan Ayckbourn. Azema is the closest echo we get to the hysterical ancestors of Zulawski’s famed female freak-outs, at the top of which resides Isabelle Adjani’s grand mal miscarriage amidst oozing milk, eggs and various bodily fluids in the subway from Possession tied with Polish actress Iwona Petry’s vodka infused, snot garnished rants in the fantastic and underrated Szamanka (1996). Here, Azema gets a handful of smaller yet entertaining moments, a stressed out B&B owner who falls into paralytic fits and unpredictable bouts of screaming. A brief sequence finds her wielding an axe in the middle of the night, not unlike Faye Dunaway in a memorable Frank Perry camp classic. But she garners a handful of laughs with her constant griping, lapsing without warning into either castigating tirades or reduced to a puddle of tears.

Instead, for the first time, Zulawski shifts his unravelling to that of a male protagonist and Jonathan Genet gets the brunt of the heavy lifting, and the lithe performer, who resembles a young, androgynous version of Vincent Cassel, dashes about as if in an increasingly intense fit of mania. Johan Libereau, of Andre Techine’s The Witnesses (2007) and Rebecca Zlotowski’s Grand Central is the comic foil, returning from his nightly excursions with fresh and increasingly worsening bruises from what we assume to be risqué sexual conquests. Their relationship prior to their stay with the Woytis family is left undefined, and they couldn’t seem to be more opposite in interest or temperament.

Witold, the failed heterosexual academic, is a cerebral ball of paranoia and anxiety, while Fuchs (who fantasizes about having been cast in Pasolini’s 1968 Teorema as the interloper who sleeps with everybody) is (at the very least) a bisexual, shamelessly vapid good-time fashion guru. Together, they exemplify the sole important aspect of successful friendship—the ability to enable one another’s madness without stepping on one another’s feet.

Zulawski, adapting Gombrowicz himself, streamlines this complicated mix of mystery template into something that seems more a stream-of-consciousness exercise, with the very nature of language and meaning collapsing into some undefined goo. From Tolstoy to Sartre, literary allusions abound, confuse, and repeat. “Words, words, words,” of Shakespeare’s Hamlet, a phrase used twice in passing critique, is bandied about with bits of pop culture cinema references, wherein the garbled, idiosyncratic speech of Leon begins to mar names like Spielberg and Bresson (not Luc Besson?), and more modern references like an alibi involving the attendance of the last Star Wars film for one character. His own works gets wound up in these word puzzles, with Libereau’s character commenting on what a terrible title The Most Important Thing is to Love is, Zulawski’s famed 1975 film (ironically, that film provides us with Zulawski’s only other queer character in his oeuvre, played by Klaus Kinski).

As far as Zulawski’s own filmography goes, the conflagration of templates in Cosmos aligns this most with something like the gangsters of his Dostoevsky adaptation, L’amour Braque, that zany, seemingly cocaine fueled exercise which first introduced him to Sophie Marceau, who he’d remain with through 2000 following his last cinematic effort, La Fidelite. Portuguese actress Victoria Guerra assumes the role of the transfixing ingénue, and is featured in her own choice moments of weirdness as the object of Witold’s obsession.

Two other major Andrzejs contribute significantly to the mise-en-scene. Composer Andrzej Korzynksi’s unscrupulously corny score announces either twangs of menace or soap-operatic weirdness. But the film’s real energy of unease comes from the incredibly agitated camerawork of DoP Andrze Szankowski, who lensed Raul Ruiz’s last two films along with actress Fanny Ardant’s directorial debut.

In Cosmos, it’s as if the film never quite stands still, flitting about between scenes from peculiar, sometimes off-putting angles, to roving madly over its subjects on an endless, pacing track, as in a near nauseating dinner-table sequence where the residents of Woytis’ weird little abode take a strange excursion and meet up with a host of other bizarre characters, including the doppelganger of their lip-deformed maid. Capturing a fetid, increasingly moss covered landscape where the rocks, trees, and water are all covered in oozy algae, this beautiful insanity begins to recall Wojciech Has’ mental asylum epic The Hourglass Sanatorium (1973). Produced by Paulo Branco, head of Alfama Films, a distributor who revels in pronouncedly offbeat auteur fare along the same lines as Said Ben Said Productions, this is a delightfully obstinate bizarro zone, and Cosmos definitely lives up to Zulawski’s reputation for haunting emotional exaggeration.

In the increasing confusion of names, quotes, and relationships (for every literary figure Witold name drops, Fuchs feigns ignorance to highlight the pretentiousness), Zulawski highlights the dangerousness of intense introspection. “We often confuse the pretty with the good,” explains Witold, quoting Tolstoy, a secondary figure to the prominent inclusion of Jean-Paul Sartre. A serious of arbitrary details are assembled by these delusional minds into crackpot theories, the self-fulfilling prophecies of one’s own self-made, utterly selfish perspective. Zulawski omits the obvious Sartre quote, “Hell is other people,” a hypothesis exemplified by the insanity of the Woytis clan, a bourgeois family crushed beneath the crumbling façade of their fading privilege. Hell is also a black hole, and every absence in each person’s life (and we all lack or are in search of something) must be filled or satisfied—and it’s usually whatever has gravitated into our own personal orbit.

With its failing social customs, allowing for Witold and Fuchs access to the Woytis’ world, Cosmos reflects even their exterior universe in a pronounced stage of decay. In the midst of its weird finale, where its characters each imagine their own private endings, the priest, a heretofore lurker at the narrative threshold, unbuttons his pants to unleash a swarm of buzzing flies. It’s as if Zulwaski wishes to announce there’s nothing sacred left here, and while we each craft our own private cosmos, we still cannot escape an inevitable descent into the eternally dissatisfied quarters of our inherent nature.

★★★★/☆☆☆☆☆