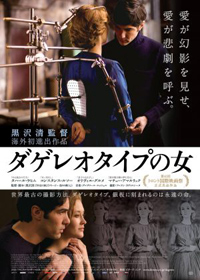

Spirits of the Dead: Kurosawa Continues Ghostly Leitmotifs in First French Language Film

Japanese auteur Kiyoshi Kurosawa makes a surprise venture into French language cinema with the intriguingly titled Daguerrotype (which is a better fit than its original English language moniker, The Woman in the Silver Plate, but in French is known as La Secret de la chamber noire, which is something more like The Secret of the Dark Room). The title invokes the first publicly known type of photographic processing, utilized exclusively from 1839 to about 1860 before other less expensive processes were discovered. Kurosawa’s narrative, co-written by Catherine Paille (of Cedric Kahn’s A Better Life, 2011) and Eleonore Mahmoudian, concerns a crotchety daguerreotype photographer who has retreated from the world into his countryside manor following the death of his wife. Obsessed with this archaic mode of photography, he takes on a new, young assistant, who inadvertently begins to have feelings for his boss’ daughter. Ghostly apparitions and interactions are often featured in Kurosawa’s filmography, and while this latest straightforward venture is sometimes transparent and predictable, it’s a deliciously measured dish on madness and obsession featuring three dubious personalities stuck in a crumbing façade, evoking the fatal ambience of the supernaturally inclined Edgar Allan Poe.

Japanese auteur Kiyoshi Kurosawa makes a surprise venture into French language cinema with the intriguingly titled Daguerrotype (which is a better fit than its original English language moniker, The Woman in the Silver Plate, but in French is known as La Secret de la chamber noire, which is something more like The Secret of the Dark Room). The title invokes the first publicly known type of photographic processing, utilized exclusively from 1839 to about 1860 before other less expensive processes were discovered. Kurosawa’s narrative, co-written by Catherine Paille (of Cedric Kahn’s A Better Life, 2011) and Eleonore Mahmoudian, concerns a crotchety daguerreotype photographer who has retreated from the world into his countryside manor following the death of his wife. Obsessed with this archaic mode of photography, he takes on a new, young assistant, who inadvertently begins to have feelings for his boss’ daughter. Ghostly apparitions and interactions are often featured in Kurosawa’s filmography, and while this latest straightforward venture is sometimes transparent and predictable, it’s a deliciously measured dish on madness and obsession featuring three dubious personalities stuck in a crumbing façade, evoking the fatal ambience of the supernaturally inclined Edgar Allan Poe.

Still mourning the death of his wife, famed photographer Stephane (Olivier Gourmet) drowns out his sorrows completing life sized daguerreotypes of his daughter Marie (Constance Rousseau) in his private studio. In need of a younger male assistant who can help move around the cumbersome materials required, Stephane finds Jean (Tahar Rahim), a young drifter eager to stumble into a profession but who has not had formal training and no knowledge of photography. Since this is exactly the type of person Stephane is looking for, Jean is hired. But things are a bit out of sorts at the photographer’s home. A strange blonde woman sometimes floats around the house, wearing a blue dress Stephane’s daughter Marie has been photographed in. At the same time, Marie is making plans to leave her father behind, and makes Jean complicit in her scheme, which makes the young man begin to have feelings for her. Meanwhile, a colleague of Stephane’s (Mathieu Amalric) introduces him to his cousin in real estate (Malik Zidi), who wants Jean to help convince Stephane to sell his land for a new greenhouse project promising to an exorbitant amount of money if he sells. But Jean finds he knows Stephan less well than he thinks when he agrees to meddle in the family’s affairs.

More of a lateral move than anything, Daguerrotype finds Kurosawa in a reserved mode, and is sometimes comparable to some of his best works, like Cure (1997) and Pulse (2001). It’s certainly more austere than the schmaltzy Journey to the Shore (2013), and yet nowhere near as delightfully offbeat as serial killer thriller Creepy (2016), which premiered several months prior at the Berlin International Film Festival. The more surprising elements of Daguerrotype involve Kurosawa playing with gender reversal in this familiar formula (the less said the better, though many will most likely be unsurprised by a last minute reveal), where a stranger invades a dysfunctional familial dynamic and upsets the disastrous balance previously established.

If the textual metaphors are a bit obvious, it only enhances the mood of impending doom for its troubled trio. Olivier Gourmet, a regular player in the Dardennes Bros.’ filmography, is in overbearing employer mode (seen recently in Grand Central and Two Days, One Night to similar effect), a bitchy control freak who belittles models when he’s forced to do fashion shoots (allowing for a brief snatch of Mathieu Amalric to explain Stephane is internationally renowned) and as equally abrupt with Rahim’s Jean, a man he hired solely for his ignorance.

The daguerreotype process demands subjects sit still for profane periods of time, leading Stephane to abuse his daughter’s docility in demanding her as the usual subject of his portraits (taking her mother’s place, so to speak). But in the late hours of the night, Stephane believes he hears his wife’s voice, playing on known superstitions about daguerreotype photography allowing subjects a kind of immortality (culminating in a sequence which perhaps equals the poetic alarm Kurosawa accomplished in a spilled water sequence in Cure).

On the other hand, daughter Marie wishes to pursue botany, even though she’s not formally trained. Her lush greenhouse is being slowly poisoned by the chemicals from her father’s photography as they seep into the ground. If that’s not clear enough, during a job interview for a position in her field (which will take her to nearby Toulouse and away from daddy’s clutches), she explains she admires plants because they ‘control their own environment.’ Meanwhile, Jean tries to daguerreotype some of her plants, something Stephane quickly forces him to terminate, a symbol of an object he cannot control, only kill.

As Marie, Rousseau is fittingly docile, while Rahim is somewhat of the wild card, his performance thwarted into a sort of unyielding monotony while Kurosawa increasingly muddies the waters by suggesting either one of the two men is an outright loon, but perhaps neither are good for Marie. Juxtapositions of the ghostly and the living, men and women, past and present, love and pain all tend to overlap, while Alexis Kavyrchine’s cinematography and production design from Pascal Consigny and Sebastien Danos assist in a establishing a visual tone as antiquated as Stephane’s vintage photography.

★★★½/☆☆☆☆☆

Reviewed on September 11th at the 2016 Toronto Int. Film Festival – Platform Programme. 131 Minutes