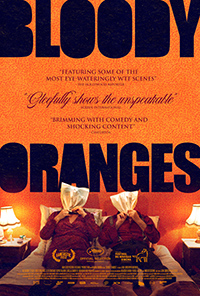

Strange Fruit: Meurisse Gets Gonzo with Slice of Cinema Bizarre

Director Jean-Christophe Meurisse follows up his 2016 comedy Apnee with something a bit more uncomfortable in its droll observations of contemporary France with Bloody Oranges. Technically a social issue comedy taking a hard left turn into horror, it’s odd intermingling of characters, story lines, and tonal elements position Meurisse, perhaps best revered for his theater work, as the next Gallic cult filmmaker.

Director Jean-Christophe Meurisse follows up his 2016 comedy Apnee with something a bit more uncomfortable in its droll observations of contemporary France with Bloody Oranges. Technically a social issue comedy taking a hard left turn into horror, it’s odd intermingling of characters, story lines, and tonal elements position Meurisse, perhaps best revered for his theater work, as the next Gallic cult filmmaker.

Marrying psychosis to capitalism with a dash of feminism, who is to say if anyone really wins, suggesting trauma and tragedy are potentially up for interpretation based on one’s own penchant for cynicism. Still, for fans of offbeat cinema sprinkled with shocking splashes of violence, Meurisse finds an odd cross section of arthouse and exploitation.

A retired couple (Olivier Saladin, Lorella Cravotin) are secretly facing bankruptcy, but have set their sights on winning an upcoming dance contest to save themselves rather than asking their children for assistance, one of whom is a successful lawyer (Alexandre Steiger). Their narrative will eventually find odd intersections with the recently disgraced Minister of Finance (Christophe Paou), accused of tax evasion, teenager Louise (Lilith Grasmug) eager to lose her virginity, and a sexual maniac whose perversities know no bounds.

The set-up may feel a bit familiar, even in its sordid leaning oddness, revealing a painstaking quartet of storylines populated by the sort of unlikeable personalities one finds in the cinema of Benoit Delepine and Gustave Kervern (a cameo from Blanche Gardin, who headlined their 2020 title Delete History, as an overly complimentary OB/GYN, solidifies this element). And then, with a foreboding insidiousness, Meurisse employs Antonio Gramsci’s popular quote “The old world is dying, and the new world struggles to be born: now is the time of monsters” to announce a swift turn into madness.

An intersecting night of debauchery and desperation plays like Quentin Dupieux’s version of the finale in Requiem for a Dream, the aftermath of which veers between comic versions of Haneke or Tomas Alfredson’s Four Shades of Brown (2004), a film also benefitting from a strong theatrical background. To say more would be to ruin the shock value, but up until these moments Meurisse presents a host of characters on the verge of hysteria.

From the bankrupt couple, their own disastrously selfish children, a smarmy Minister of Finance and a sex positive teen, all are unexpectedly complex in their responses to, well, extreme conflict. Interestingly, Christophe Paou’s Minister is being honest when he confides to a reporter his greatest weakness is telling the truth (even as it’s an attempt to distance himself from scandal, with Denis Podalydes popping up frequently to challenge his sexuality and provide counsel), while Grasmug’s Louise doubly upends gender norms as a teen girl in two diametrically opposed sexual interactions.

Like an episode of “Black Mirror,” there are subtexts about society, capitalism, nationalism, misogyny, and indifference (the film opens with a contentious panel of dance contest judges in a tiff about exceptions for handicapped competitors). And if one comes away with visions of Boorman’s Deliverance (1972) dancing in their mind’s eye, consider its salty-sweet title, conjuring the OG trick of using a sack of oranges to cause internal bruising or bleeding (think the punishment Anjelica Huston was subjected to in The Grifters, 1990). The fruit will retain its viability, but maybe we won’t.

Reviewed at the 2021 Cannes Film Festival July 9th – Midnight Program. 102 Mins.

★★★½/☆☆☆☆☆