They Knew Him Well: Malick’s Sublime Existential Search for the Pearl

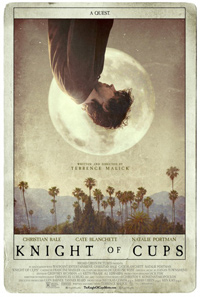

To many, Terrence Malick, perhaps the most revered of modern American auteurs, has ascended to his own idiosyncratic, esoteric doss, entering his most prolific decade in his forty years of filmmaking with confounding illustrations of pronounced existential ennui. Following 2011’s Palme d’Or winning The Tree of Life, he unleashed the belabored To the Wonder, cementing a pretentious predilection for wandering, rambling lost souls. His latest, Knight of Cups is certainly as impressionistic as these last two features, and hinges once again on a restless nomad, this time a faded Hollywood screenwriter hovering betwixt the sacred labors of his profession and the profane temptations of his surroundings. Inundated with notable celebrities, it’s too abstruse for a legion of starfuckers to fathom, much less righteously embrace its rather obvious critique of how completely commodifying an art form eventually results in the dehumanization of not only artists but audiences as well.

To many, Terrence Malick, perhaps the most revered of modern American auteurs, has ascended to his own idiosyncratic, esoteric doss, entering his most prolific decade in his forty years of filmmaking with confounding illustrations of pronounced existential ennui. Following 2011’s Palme d’Or winning The Tree of Life, he unleashed the belabored To the Wonder, cementing a pretentious predilection for wandering, rambling lost souls. His latest, Knight of Cups is certainly as impressionistic as these last two features, and hinges once again on a restless nomad, this time a faded Hollywood screenwriter hovering betwixt the sacred labors of his profession and the profane temptations of his surroundings. Inundated with notable celebrities, it’s too abstruse for a legion of starfuckers to fathom, much less righteously embrace its rather obvious critique of how completely commodifying an art form eventually results in the dehumanization of not only artists but audiences as well.

Rick (Christian Bale), a disillusioned screenwriter, spends his time vaguely listening to film studio executives as he drifts in and out of his own particularly stale self-abasement. In-between a myriad of swank parties (one sprawling bacchanal featuring a hodge-podge of Hollywood notables, from Nick Kroll to Joe Mangianello to Fabio to Jocelin Donahue), Rick seems to be on a merry-go-round of trysts with beautiful women (Imogen Poots, Freida Pinto, Teresa Palmer, Natalie Portman, Isabel Lucas) each defining a particular chapter of his odyssey while he slowly meanders into defining the life he actually desires. At the same time, he finds himself lost in fretful memories concerning his emotionally troubled father (Brian Dennehy), his recovering addict brother (Wes Bentley) and ex-wife (Cate Blanchett).

Once again, Malick strikes divisive chords with his mixture of religious and pagan symbolism. The tarot card of the title represents a grand adventurer in need of constant stimulation, and when reversed becomes emblematic of a person prone to recklessness, unable to decipher the difference between truth and falsehood. Obviously, this is an allusion to Rick’s profession, a notable somebody in the world’s largest manufacturer of celluloid dreams, all more or less tied to a sprawling city known for its proliferation of psychics and mediums as both tourist attractions or acceptable lifestyle conditions. But here’s where many have mistaken Knight of Cups as merely another flawed odyssey of Malick’s, wherein audiences are simply tasked with humoring the auteur’s predisposition for ethereal flair.

Arguably, this is one of the most achingly profound portraits of contemporary Los Angeles, a city with stunningly beautiful facades, the penultimate shrine to American cinema. The possibilities suggested in the landscape’s veneer appear boundless, and yet it’s a city so frustratingly, damnably superficial, made exclusively so by an industry eating its own tail in the pursuit of immortality based solely on aesthetic.

Malick juxtaposes this with a constant omniscient retread of the Hymn of the Pearl, a Manicheistic flourish assigned to Rick’s familial woes (wherein resides the main thrust of spirituality tainted by the obvious markers of materialism), an anguished Brian Dennehy and Wes Bentley duking it out as they forever mourn the death of a beloved family member. Rick is aligned with the “the son of the king of kings” from the hymn, who is tasked with retrieving a pearl from a serpent but is seduced by the Egyptians and forgets who he is. Eventually, he’s reminded by a messenger who is presumed to be Jesus Christ. The pearl in question, alluded to in these constant poetic asides as the other white of the eye, is a metaphor for the glint of actual humanity in the very windows leading to the proverbial soul.

But while these moments may be more pronounced than, say, the mumblings of the Sean Penn character in The Tree of Life, (another character as taxing metaphor for broken down meaninglessness in a life consumed by modern materialism), it’s perhaps a bit heady to expect most audiences to reflect on such profundity. But paired with Emmanuel Lubezki’s exquisite cinematography, this portrait of a man who’s forgotten himself is the pinnacle of cinematic achievement, a roving, endlessly famished spirit gliding through exclusive industry parties and a series of famed tourist attractions also serves as a document of Los Angeles’ (and its geographical hedonistic twin sister, Las Vegas) continuous wonders.

Divided into chapters each representative of a tarot attribute, the meanings assigned are perhaps meant to be as arbitrary as these designations. A cadre of beautiful women gild each of these chapters, eventually posing a repetitive objection to an otherwise compelling deliberation on desolation. In truth, yes, these relationships are dull, even uninspired. An early segment featuring Imogen Poots succinctly defines Rick’s desires, “You just want a love experience.” But Malick’s design, enhanced by his quartet of editors (A.J. Edwards, Keith Fraase, Geoffrey Richman, Mark Yoshikawa) recalls the sketches as portraiture of Antonio Pietrangeli’s I Knew Her Well. There are moments of stunning visual acuity here, paired with a restless melancholy sure to instigate awe purely for their sheer, unfathomable beauty, with credit also due to Malick’s usual production designer Jack Fisk.

We learn very little of Rick, much like the central female in the Pietrangeli film (both of these have been freely compared to works by Federico Fellini, as well), except the only semblance of human connection, at least in the commodified metropolis, is through the tired superficiality of romantic flings. As indicated by the tearful remonstrance of the ex-wife character represented by Cate Blanchett, emotional attachments are doomed to become less concrete or clearly defined, the highs fewer and far between (take the screen time give to Poots vs. the late appearance of Lucas), calling for more extreme measures (Natalie Portman’s adulterous character), but always prone to fail since the pursuit of happiness is merely a debauched, self-serving fantasy.

Malick premiered the film at the 2015 Berlin Film Festival, where it ultimately went home empty handed (and unfairly so). Gloriously cinematic, Knight of Cups may be doomed as far as box office glory is concerned, but this isn’t more kindling merely for unquestioning, diehard aficionados of the auteur. Rest assured, time will reclaim the glorious attributes of this film, perhaps when audiences will have recovered from their soma comas and the vacuous obsessions of trending potential. Simply put, Knight of Cups is, without a doubt, a sublime piece of cinema.

★★★★½/☆☆☆☆☆