Bjorn Again: Lindstrom & Petri Examine the Plight of the Beautiful and the Damned

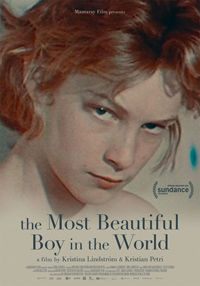

For those unfamiliar with the name Bjorn Andresen, the documentary The Most Beautiful Boy in the World only scratches the surface of his unique trajectory. Handpicked by Luchino Visconti to star in his 1971 adaptation of Thomas Mann’s Death in Venice, the Swedish born teenager became an overnight sensation and would forever be branded by the auteur’s comment about him, a trademark which would hinder him indefinitely. After appearing in a notable moment in Ari Aster’s 2019 title Midsommar, it seemed a ripe time for recuperation, and the rationale behind this documentary portrait from Kristina Lindstrom and Kristian Petri is a no-brainer. But whatever interest and access originated this project, there’s also a sense of much either being left unsaid for comfort’s sake or mere reluctance on both the directors’ and subject’s part in illuminating what’s actually of interest.

For those unfamiliar with the name Bjorn Andresen, the documentary The Most Beautiful Boy in the World only scratches the surface of his unique trajectory. Handpicked by Luchino Visconti to star in his 1971 adaptation of Thomas Mann’s Death in Venice, the Swedish born teenager became an overnight sensation and would forever be branded by the auteur’s comment about him, a trademark which would hinder him indefinitely. After appearing in a notable moment in Ari Aster’s 2019 title Midsommar, it seemed a ripe time for recuperation, and the rationale behind this documentary portrait from Kristina Lindstrom and Kristian Petri is a no-brainer. But whatever interest and access originated this project, there’s also a sense of much either being left unsaid for comfort’s sake or mere reluctance on both the directors’ and subject’s part in illuminating what’s actually of interest.

A chance opportunity defined this indifferent persona forever, while the assumed trauma of sexual objectification remains a blurred gray area when such ambiguities beg for explication. As such, it’s a portrait which provided an opportunity for Andresen to take back his own narrative. Instead, there’s a trenchant disinterest in this presentation, while several elements coaxed together relay ambiguous snapshots from then and now while (mostly) overlooking nearly four decades of events in between.

The casting of unknown teenager Bjorn Andresen as Tadzio in the 1971 film Death in Venice had resounding ripple effects on the young man’s life. Under contract to Visconti, he wouldn’t appear in another film project for several years, instead becoming a musical sensation in Japan. As years and romances pass, more personal tragedy marks Andresen’s life, still grappling with the instances surrounding his mother’s abandonment and death in 1962. While appearing in Midsommar in 2019, Andresen seemed once again poised as a figure of intrigue in modern film productions. But his initial entry into the cinematic universe continues to define and weigh on him as he attempts to define his own interests, relationships, and overall purpose.

Initially, Lindstrom and Petri appear to paint Andresen as a ghost haunting his own memories, a white-haired specter wandering about in the past. The twin traumas of his mother’s abandonment and death are as obliquely recounted as the surreal presence of Visconti, whose attraction to Andresen created a situation which held him captive (one wonders what a more pointed expose of how fame and celebrity born from objectification might have played, especially concerning a male heterosexual subject confronted with the glare of a queer male gaze—and how this might have mirrored or clashed with another of Visconti’s darlings, such as Helmut Berger in 1969’s The Damned). The only trauma pit stop between his output as a teenager and his contemporary vulnerabilities is the death of one of his children in the late 80s due to SIDS.

While sordid details are hardly necessary to showcase Andresen and his experiences, it’s curious to see such skirting around Andresen’s actual feelings about Visconti or how he contended with the affections and attentions of gay men only to then showcase his intimate dysfunctions with a much younger romantic partner, Jessica. Likewise, while time is spent detailing Andresen’s pop icon status as a musical sensation in Japan, profound opportunities are often eclipsed.

From his manager Max Seki to manga artist Riyoko Ikeda, who popularized the series “Lady Oscar” after the likeness of Andresen, they both vocalize, even on a meta level, cultural responses to Andresen. Eerily, it’s a situation which recalls the mega success of The Runaways in Japan, and the spiral of Cherie Currie.

Of the many references to the interpretations of Tadzio, who represents “intellectual death” for his fictional aged admirer, the parallels to Andresen’s own life are presented but not examined in depth. “To put your eyes on beauty, one puts their eyes on death,” is the decadent inheritance of Tadzio’s legacy. Andresen’s trajectory instead recalls Rilke, “For beauty is nothing but the beginning of terror…,” a terror which feels as if it’s hibernating outside the frames of The Most Beautiful Boy in the World.

Reviewed on January 29th at the 2021 (virtual) Sundance Film Festival – World Documentary Competition. 94 Mins

★½/☆☆☆☆☆