Spaces Between: Green’s Controlled, Heavily Stylized Metaphor

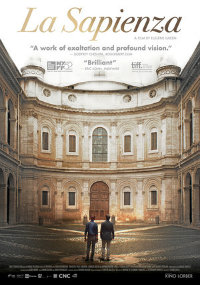

Eugène Green is an American born filmmaker who has been steadily making foreign films over the past decade or so, more often than not in French. With his fifth feature, La Sapienza (Italian for ‘the wisdom’), Green provides a playful experiment of heavily stylized tone, focusing intently on specific, purposeful compositions that lends the film a rather off-putting dramatic pallor, especially for those seeking to emotionally engage with the material. Even as it explores certain ideas pertaining to the relationships between people, their past and present, and the distance between time, memory, and themselves, the film’s rigid artificiality often works staunchly against its overall effectiveness.

Eugène Green is an American born filmmaker who has been steadily making foreign films over the past decade or so, more often than not in French. With his fifth feature, La Sapienza (Italian for ‘the wisdom’), Green provides a playful experiment of heavily stylized tone, focusing intently on specific, purposeful compositions that lends the film a rather off-putting dramatic pallor, especially for those seeking to emotionally engage with the material. Even as it explores certain ideas pertaining to the relationships between people, their past and present, and the distance between time, memory, and themselves, the film’s rigid artificiality often works staunchly against its overall effectiveness.

Frustrated architect Alexandre (Fabrizio Rongione) decides to take his wife Alienor (Christelle Prot) on a trip with him to Italy where he plans to research 17th century architect Francesco Borromini. It’s apparent that their relationship has become a stagnant union, though it’s not at first clear as to why (perhaps Alexandre’s attraction to Borromini, who specialized in shapes and patterns instead of the inspiration from the human forms that defined the works of his peer’s, points to a predilection for distance and coldness). They stumble upon a sickly girl, Lavinia (Arianna Nastro), being helped by her brother Goffredo (Ludovico Succio). She seems to be suffering from wasting disease, as her brother explains when they drop her off at home, and Alienor commits to staying near Lavinia to help her recover, advising Alexandre to take Goffredo, a student of architecture, with him to Rome as a guest.

Premiering at the 2014 Locarno Film Festival, La Sapienza is intriguingly offbeat, especially when focusing on its estranged couple, played by Fabrizio Rongione and Christelle Prot. Rongione is featured in many of the films by the Dardenne Bros, including their last feature, Two Days, One Night, while this is the fourth time Prot has starred in a film of Green’s. Amusingly, they seem to be like zombies as the film opens, going about their methodical, daily activities as if wandering through a perpetual fog. Of course, this distancing effect is extended to our own feelings towards them, as Green seems to be proving that by continually breaking the fourth wall when the actors stare directly into the camera, their monotonous lines addressing the other performer as they look at us. We may be invited into their space, but it hardly makes us feel closer to them. In fact, as with marriage, the closer two people (or objects) are, the farther away they seem to be. While this makes for distractingly dry material in relation to its treatment of a strained marriage, it makes for a refreshing visualization….except for the fact that Abbas Kiarostami’s Certified Copy (2010) does something similar and to much better effect.

As enjoyably terse as Rongione happens to be, Prot seems to channel a sort of distilled empathy (seen best in an opening sequence at work where she listens to a list of statistics about a populous of poor, unhappy people, where numbers have been used to define the overall emotional potential of a whole group), younger performers Ludovico Succio and Arianna Nastro are grating, unable to enliven such lofty, philosophical dialogue. Because of this, our focus lingers on Raphael O’Byrne’s appreciative camera roaming throughout a variety of Italian architectures, as if we’re on a travelogue tour through these edifices, with Rongione’s Alexandre providing us with key information. And just as each ‘pair’ of characters is drawn to be in exact, theoretical opposition of one another, they are nevertheless united in visual composition, and Green lingers on objects after his characters leave the screen, such as two empty champagne flutes, or an empty dinner table. Goffredo asserts that architecture is a space that encloses us but we are also, simultaneously free, a hypothesis that Alexandre seems to initially oppose, but eventually embrace as his trip with Goffredo allows him to embrace the joie de vivre he had lost.

If only Green’s screenplay didn’t get bogged down with distracting silliness. “The treasure of dawn is sapience,” Alexandre says at one point. And at the film’s awkward finale, conflict resolution seems forced (not surprising since this quartet often feel like echoes of actual characters), Succio’s Goffredo has to utter all kinds of clunky dialogue, telling his sickly sister that “This is the last day of our childhood.” Interesting, if not always entirely successful, La Sapienza is languid, and even sometimes hypnotic. But the stilted performances tend to grate whenever we’re dealing with actual emotions, such as the explanation for the strained relationship between husband and wife, or what seems to be a comical aside involving an angry Australian tourist.

★★½/☆☆☆☆☆