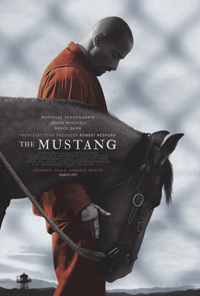

They Shoot Horses, Don’t They?: de Clermont-Tonnerre Leads Us to Water with Minimalist Melodrama

Animal love is at the heart of Laure de Clermont-Tonnerre’s directorial debut, The Mustang. At least as a conduit for recovery and return to lost humanity in its depiction of a compelling, progressive horse-training program offered at smatter of prison systems throughout the United States. The singularity of its title is at odds with the subtitled statistics gracing the beginning and end of the narrative, which elude to the troubling process by which wild roaming mustangs are still captured across the American plains, many to be nonchalantly euthanized while a lucky few are shunted off into more unique situations such as this. They’re at odds because de Clermont-Tonnerre seems to be seeking a more universal conversation as she marries metaphors concerning her sullen protagonist and the wild mammal whose bondage and temperament he clearly relates to, and instead seems to skirt in the realm of the superficial with a minimalism less striking than it is emotionally amorphous.

Animal love is at the heart of Laure de Clermont-Tonnerre’s directorial debut, The Mustang. At least as a conduit for recovery and return to lost humanity in its depiction of a compelling, progressive horse-training program offered at smatter of prison systems throughout the United States. The singularity of its title is at odds with the subtitled statistics gracing the beginning and end of the narrative, which elude to the troubling process by which wild roaming mustangs are still captured across the American plains, many to be nonchalantly euthanized while a lucky few are shunted off into more unique situations such as this. They’re at odds because de Clermont-Tonnerre seems to be seeking a more universal conversation as she marries metaphors concerning her sullen protagonist and the wild mammal whose bondage and temperament he clearly relates to, and instead seems to skirt in the realm of the superficial with a minimalism less striking than it is emotionally amorphous.

Transferred to a remote prison compound in the Nevada desert, lifer Roman (Matthias Schoenaerts) is twelve years into his sentence, emotionally closed off from all. In vain, a prison psychologist (Connie Britton) attempts to discern his interests in order to assist his acclimation to a new environment, determining Roman would be best served working outdoors with minimal contact. A chance encounter with a newly acquired wild mustang, animals which are used in a program where prisoners train the horses so they can be auctioned off to various law enforcement agencies at the end of their tenure, finds Roman roped into facing off with the fiery horse, an animal which proves difficult to approach. But the two caged creatures gravitate towards one another and slowly Roman finds he’s able to begin opening up emotionally.

While the underwhelming impact of The Mustang doesn’t rest entirely on the shoulders of Matthias Schoenaerts, a sense of clichéd familiarity is assisted by the estranging moroseness which initially made him such a hulking and compelling mixture of toxic masculinity and repressed emotion in his 2011 breakout Bullhead. The persona is an established trademark for the actor, which was continued in his following collaborations with Belgian director Michael R. Roskam (including the successful English language The Drop in 2014 and the abysmal neo-noir romance Racer and the Jailbird in 2017). But a glaring lack of nuance in de Clermont-Tonnerre’s script (co-written by Mona Fastvold and Brock Norman Brock) leads to more telling than showing, as evidenced by the Jason Mitchell character’s continual interpretations of Roman’s body language. Besides Mitchell, several other supporting players also attempt to resist stereotyping, such as Connie Britton’s kindly psychologist and Bruce Dern’s persnickety program manager. However, none of them are able to rightly contribute to the local flavor of the prison system, which is presented simply as a peripheral, abstract miasma of entrenched hierarchies according to race and contraband. While there’s a well-played emotional reckoning between father and daughter (Gideon Adlon), the build-up to it feels too predictable and its eventual resolution too clean, exemplifying The Mustang’s perfect storm of events reaching for a sort of Steinbeckian treatise on contemporary working class American systems of oppression.

While the ideas behind The Mustang merit considerable interest, this is a far cry from the accomplished The Rider (2017) from Chloe Zhao, mostly for its dependence on taken-for-granted absolutes. On the surface, de Clermont-Tonnerre has a handsomely staged minimalist melodrama on her hands, but its juxtaposed tangents seem to demand either more lavish emotional interiority or less attenuation to anything outside the narrative fringe of a man and his horse.

★★/☆☆☆☆☆