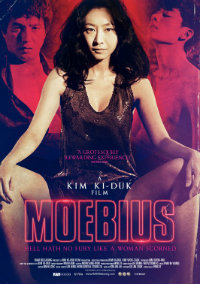

Freudian Slip: Ki-duk Gets to the Greek

South Korean auteur Kim Ki-duk outdoes himself with his latest theatrical release, Moebius, so named for the continuous strip in reference to a family suffering from tragicomic sexual perversities of mythological proportion. Perhaps a natural modernization of Socrates’ Oedipus, it instead feels like Ki-duk is trying to one-up Von Trier’s Antichrist (2009), his triangle of victims suffering in near silent pantomime. It’s this absence of language, as not a line of dialogue exists, (though verbal communication is sometimes shown as transpiring, though out of logical auditory range), that not only makes this lurid material a bit more palatable but also fashions the film into a perverse kind of visual poetry. Those turned off by the extreme sex and violence peppered throughout his 2013 Golden Lion winner, Pieta, won’t be won over by Ki-duk with this oddity, but it’s a ballet of dark desires that seems more inventive after a second viewing, when its shock value takes a back seat to its artistry.

South Korean auteur Kim Ki-duk outdoes himself with his latest theatrical release, Moebius, so named for the continuous strip in reference to a family suffering from tragicomic sexual perversities of mythological proportion. Perhaps a natural modernization of Socrates’ Oedipus, it instead feels like Ki-duk is trying to one-up Von Trier’s Antichrist (2009), his triangle of victims suffering in near silent pantomime. It’s this absence of language, as not a line of dialogue exists, (though verbal communication is sometimes shown as transpiring, though out of logical auditory range), that not only makes this lurid material a bit more palatable but also fashions the film into a perverse kind of visual poetry. Those turned off by the extreme sex and violence peppered throughout his 2013 Golden Lion winner, Pieta, won’t be won over by Ki-duk with this oddity, but it’s a ballet of dark desires that seems more inventive after a second viewing, when its shock value takes a back seat to its artistry.

An alcoholic and arguably deranged housewife (Lee Eun-woo) wrestles violently with her husband (Cho Jae-hyun) while their teenage son (Seo Young-ju) nervously looks on. A phone call on the husband’s cell phone instigated the argument, and we soon learn it’s the husband’s mistress (also Lee Eun-woo—a woman is a woman, it seems). After taking the mistress out on a date and copulating in a parked vehicle, the wife breaks a window in the business owned by the mistress and then attempts to dismember her husband. Her attempt thwarted, she scurries to her son’s room, who just so happens to be masturbating, and cuts off his penis. While father takes son to the emergency room, mom flees into the night, leaving the men to pick up the pieces, so to speak. As the son learns to live with his shamedful new existence, which sees him get involved with a gang of older boys who goad him into the gang rape of a convenience store owner, the father becomes wracked with guilt, obsessed with trying to find options for his son, including a penile transplant and alternative ways to derive pleasure.

Moebius plays like a Freudian inspired fever dream, Oedipus rewritten with literal rather than allegorical connotations concerning things like penis envy, fear of castration, or the mother-son incest paradigm that borrows the name. Oddly and uncomfortably funny, to describe it sounds more off-putting than it actually is, for as we watch these troubled characters navigate their strange circumstances, reactions and counter reactions play as primal, human responses.

The characters are never named, as if they’ve simply been assigned a role to play in an already scripted environment. Lee Eun-woo is heavily stylized as the unhappy wife, her makeup and wild hair making her seem like a phantom cat demon inspired by Kuroneko (1968), so it’s easy to miss she’s playing dual roles here, a flourish that recalls Masahiro Shinoda’s use of Shima Iwashita as both wife and lover in Double Suicide (1969). While Eun-woo is generally the captivating presence in her scenes, Ki-duk regular Jae-hyun and Seo Young-ju are equally impressive in their abilities, since there’s never a moment where we’re unclear of exactly what’s happening.

It’s a strange lure to keep us invested in the film even when it’s easier to look away, such as when an exploration of the thin line between pleasure and pain begins to take shape. After an impressive parental sacrifice, we end up where we began, with a new and even more bizarrely violent situation taking place by the film’s end. A Buddha figure head houses the initial castrating implement, and we end on a note revisiting this head, relocated. Underneath all our sanctimonious bids for enlightenment lies the dark, twisted, and very human nature that dangerously, inextricably, can swallow us whole.

★★★/☆☆☆☆☆