The Hand that Robs the Cradle: Mermoud Utilizes Devos for Sweet Vengeance

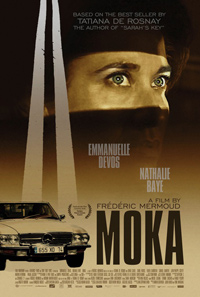

Revenge is a dish best served cold and a little neurotic, at least as presented by Frederic Mermoud in his sophomore effort, Moka, an adaptation of Tatiana de Rosnay’s novel (author of the source material for the 2010 Kristin Scott Thomas melodrama Sarah’s Key). Uniting two titans of French cinema, Emmanuelle Devos (who starred in Mermoud’s 2009 debut Accomplices) and Nathalie Baye, this perverse slow burn may not yield any real surprises but is a throwback to the tortured psychological thrillers of Claude Chabrol.

Revenge is a dish best served cold and a little neurotic, at least as presented by Frederic Mermoud in his sophomore effort, Moka, an adaptation of Tatiana de Rosnay’s novel (author of the source material for the 2010 Kristin Scott Thomas melodrama Sarah’s Key). Uniting two titans of French cinema, Emmanuelle Devos (who starred in Mermoud’s 2009 debut Accomplices) and Nathalie Baye, this perverse slow burn may not yield any real surprises but is a throwback to the tortured psychological thrillers of Claude Chabrol.

If Mermoud doesn’t manage to wring as much dramatic possibility as he could have from this scenario, wherein a mother mourning the loss of her adolescent son takes it upon herself to incite vengeance on those responsible for his death, it is often elevated from mere dime store accoutrement thanks to the anguished presence of the usually sublime Devos.

Following the tragic death of her son from a hit-and-run accident in Lausanne, the distressed Diane (Devos) gets fed up with the lack of progress in the police investigation and takes matters into her own hands by hiring a private investigator. Exploring several leads of possible vehicles in the area which matched descriptions, as well as a confirmation that the driver of the car was a blonde woman, Diane stumbles onto her prime suspect in the small spa town Evian, where beautician Marlene (Baye) and her fitness instructor ex Michel (David Clavel) are in the process of selling their vintage Mercedes coupe, a vehicle which also happens to have had some minor damage recently repaired. Posing as a potential buyer, Diane introduces herself as Helene and engages in a bidding war for the car. Meanwhile, she begins to frequent Marlene’s establishment and soon builds a familiar rapport with the friendly woman who offers Helene lodging.

Moka’s opening moments are its slyest as we watch a terrified Devos eluding detection as she sneaks out of an establishment we only later realize is a sanitarium. Shying away from her estranged husband (a routinely concerned but distant Samuel Labarthe), Devos’ Diane adopts an alternate persona, Helene (a name with equally grounded subtexts in Greek mythology) and poses as respective clients for both Marlene and Michel.

In many ways, Devos plays a character similar to the Rebecca De Mornay antagonist in the pulpy American thriller The Hand that Rocks the Cradle (1992), a woman posing as an au pair to take vengeance on the woman who brought about the downfall of her own happy marriage. But even manipulating her way into being the logical buyer of the fateful gold Mercedes coupe, Devos maintains a unique sympathetic angle, even as she purchases a handgun following a random encounter through drug dealer Vincent (Olivier Chantreau), the film’s only real clichéd misstep in an otherwise compelling face-off between the two women.

Clearly suspicious of Helene’s uninitiated kindness and feigned affection, Baye brings a weary dimension to fading beauty queen Marlene, a woman who has spent her entire life in the confines of an industry she still vainly clings to (an exchange wherein Devos flippantly insists Baye looks good for her age and then declines to define what age that is remains one of the film’s shadiest jabs). An inscrutable blonde, we’re left searching for glimpses of the self-serving monster beneath Marlene’s poise, a woman who hits all the right social cues, perhaps a bit too assuredly. The women are potentially representative of the juxtaposed social landscapes of the Swiss region Lausanne versus the privilege of France’s touristy Evian, both provinces on Lake Geneva but each holding their distinct social flavors.

With only the rumored make of the car and the hair color of the driver, Diane begins an ambivalent and somewhat confused path to vengeance. As she begins to have more and more interactions with Marlene and Michel, her resolve seems tempered, both in what could be her attraction to Marlene as a friend and Michel as a potential lover, which gives Moka its unpredictable element of anxiety as we wait for the other lethal shoe to drop.

With little mystery to its proceeding, including the third act reveal which can be easily predicted early on, Mermoud’s film is more an exercise in tension, although not the kind which will likely leave audiences on the edge of their seats. Rather, it teases a taut balance between two wary women who can’t allow one another to sense the other’s paranoia, suspicion, or rage.

★★★/☆☆☆☆☆