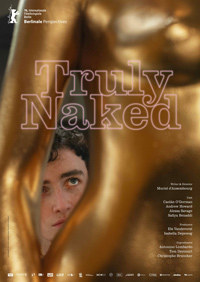

Father Knows Best: Intimacy Cuts Deepest in d’Ansembourg’s Debut

“When porn has become the norm, intimacy is the new taboo,” reads an early tagline for Truly Naked, the directorial debut of Muriel d’Ansembourg, who has built a reputation with previous short films also desiring to explore blurring boundaries in similarly uncomfortable scenarios. Her debut is technically a ‘coming of age’ film, pun intended, as it explores the maturation of a quiet teenager whose existence as the cinematographer for his father’s family business, a pornography creator, defines him. As a conversation piece, it’s a thorny hot bed of topics, ranging from dysfunctional kinship roles to how Gen Z’s development has been irreparably fashioned by mature steaming content which isn’t an accurate depiction of human sexuality or relationships. At the same time, despite the provocative milieu, it’s a narrative which tends to play softball with its subjects, and leaves its audience with a sense of some harder questions left unasked.

“When porn has become the norm, intimacy is the new taboo,” reads an early tagline for Truly Naked, the directorial debut of Muriel d’Ansembourg, who has built a reputation with previous short films also desiring to explore blurring boundaries in similarly uncomfortable scenarios. Her debut is technically a ‘coming of age’ film, pun intended, as it explores the maturation of a quiet teenager whose existence as the cinematographer for his father’s family business, a pornography creator, defines him. As a conversation piece, it’s a thorny hot bed of topics, ranging from dysfunctional kinship roles to how Gen Z’s development has been irreparably fashioned by mature steaming content which isn’t an accurate depiction of human sexuality or relationships. At the same time, despite the provocative milieu, it’s a narrative which tends to play softball with its subjects, and leaves its audience with a sense of some harder questions left unasked.

Alec (Caolán O’Gorman) is a high school student who harbors a significant secret, serving as cameraman for his father Dylan’s (Andrew Howard) homegrown online porn channel. At school, he unwittingly, but likely subconsciously, chooses the subject of porn addiction for a school project, never expecting he’ll be paired with female classmate Nina (Safiya Benaddi). As work on the project commences, an attraction grows between the two, especially as Nina observes Alec to be a sensitive, caring soul. Upon discovering the reality of his home life, her curiosity and eventual confrontation with Dylan assists Alec in making a meaningful decision about his future.

The film’s opening moment tosses us into the ring with Alec, an intimate voyeur fashioning his father’s diminishing status as a self-made porn star. Performative penetrative sex with Lizzie (played by adult actor Alessa Savage), an affable starlet who ends up being the film’s sacrificial lamb, bathed in shimmering gold paint, plays like the kinky successor to the opening credits of Goldfinger (1964). Safety concerns post-coitus confirm the paint is edible (a detail which should have been discussed in Tyler Perry’s ridiculous Mea Culpa, 2024) suggests a routine, later confirmed, of scenarios being filmed without regard or consideration for feminine anatomy. Alec’s professional demeanor, as opposed to his father’s reckless abandon, is unsettling for a teenager, not unlike a young Christina Crawford pouring cocktails for her mother’s ‘suitors.’ But this is nothing compared to the film’s most galvanizing moment when Lizzie is confronted with a large, squirming octopus as a scene partner, a creature destined to be dumped back in the ocean after fulfilling its assigned duty. While cephalopod sex is a kink which created its own pornorpgraphuc subgenre, perhaps best visualized in Kaneto Shindo’s Edo Porn (1981), it clearly exists purely as a taboo fantasy, as no one is prepared for how upsetting and strenuous this ends up being in actuality.

As daddy Dylan, Andrew Howard, who has long been a character actor reveling in villainous territories, cuts a striking figure as a parent abusing his child, the impetus for all of the film’s most uncomfortable moments of dysfunction (such as gloating over a dildo mold of his erect penis). And yet, d’Ansembourg tends to use him only for provocation, arguably as detached from sexual intimacy as he is from his own son, save for a teary remembrance of how he felt holding the infant Alec for the first time. But an inevitable reckoning between father and child feel’s muted. Alec’s eventual declaration doesn’t have the same cathartic moment as something like a parental comeuppance in This Boy’s Life (1993), for instance. Likewise the developing romance between Nina (a striking and sanguine Safiya Benaddi) and Alec, which is the catalyzing force of the narrative and absent a necessary energy which arguably should match, or at least hinder, the film’s shock value. Their multi-media school project about online porn addiction, for instance, isn’t utilized effectively, merely an on-the-nose detail suggesting they’re not actually forced to have any real-world conversations incorporating Alec’s close-to-home relationship with the subject.

Newcomer Caolán O’Gorman is effectively compelling as an innocent somewhat warped by the institutions supposedly designed to guide him, even when the third act resolutions of Truly Naked tend to consume his careful characterization. As the title suggests, actual vulnerability is an emotional reality which has been systematically eradicated from an industry historically crafted for and by the heteropatriarchy, a conversation within the film dropped like a thesis statement we never return to. d’Ansembourg edges her way to a moment, but, perhaps purposefully, avoids the catharsis of climax.

Reviewed on February 16th at the 2026 Berlin International Film Festival (76th edition) – Perspectives section. 102 mins.

★★½/☆☆☆☆☆