Fixer Downer: Cedar Unleashes Fascinating Portrait of Aggravating Underdog

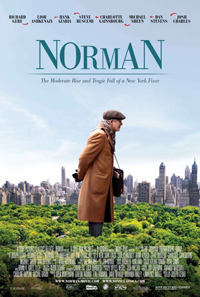

There’s an unshakeable sadness to Israeli director Joseph Cedar’s English language debut Norman: The Moderate Rise and Tragic Fall of a New York Fixer, which stars Richard Gere in one of the most profoundly melancholic performances of his five decades (and counting) career. What’s more, the film’s marketability is as impervious to synopsize efficiently (at least in modern cinematic preview language) as its narrative is unpredictable. In essence, it’s an uncharacteristic character drama about a lonely man desperately holding on to the tenacious tendencies which brought him past success (at least enough to keep him trying) in a bygone paradigm of networking.

There’s an unshakeable sadness to Israeli director Joseph Cedar’s English language debut Norman: The Moderate Rise and Tragic Fall of a New York Fixer, which stars Richard Gere in one of the most profoundly melancholic performances of his five decades (and counting) career. What’s more, the film’s marketability is as impervious to synopsize efficiently (at least in modern cinematic preview language) as its narrative is unpredictable. In essence, it’s an uncharacteristic character drama about a lonely man desperately holding on to the tenacious tendencies which brought him past success (at least enough to keep him trying) in a bygone paradigm of networking.

Whereas the term “fixer” was once a euphemism for a well-connected member of one’s social strata who knew how to hustle themselves and their ‘clientele’ into lucrative deals our out of sticky situations, the archaic terminology instead connotes instability, at least the modern environs of the story at hand. Cedar documents a titular character who is a pathetic, sometimes aggressive mooch, a man who establishes unheeded quid pro quo situations much to the chagrin of most who know him.

Norman Oppenheimer (Gere) is a lonely gentleman who lives in the margins of New York City’s elitists, having spent his life scrabbling to break into economic success through aggressive networking as a handy personality, i.e., a “fixer.” But Norman’s particular occupation involves a complicated series of tenuous promises and complex untruths, and unfortunately, people aren’t quite so patient anymore with the empty promises he has to offer, with the exception of his nephew (Michael Sheen), who keeps an eye out for the older man. But when Norman stumbles upon Micha Eshel (Lior Ashkenazi), an Israeli politician alone visiting New York and without any social prospects, Norman ingratiates himself upon the official and makes a memorable impression through an act of generosity. Three years later, Eshel becomes the Prime Minister of Israel—and has not forgotten Norman’s kindness. Chance encounters with a variety of individuals soon courts the wrong kind of attention, and Norman’s unprecedented shine is quickly rusted.

While the title Norman does as little to express the meaningfulness of Cedar’s film as its initial working title, The Oppenheimer Strategies, it does engender an incalculable sense of mystery about where Cedar is taking us. Gere’s character is a formidable addition to the director’s filmography, which includes a number of prickly, not necessarily likeable personas (like the cantankerous professor at the center of his last feature, 2011’s Footnote). And yet Norman is imbued with a striking sense of empathy for its somewhat pathetic, if well-intentioned character.

Shared sequences with Lior Ashkenazi and a striking Charlotte Gainsbourg (an enigmatic woman who works in the embassy for the Israeli Justice System) are as emotionally resonant as they are uncomfortable. These are forced social interactions on Norman’s behest which have considerable consequences on his trajectory, and unfold like bad sketch comedies which go on so long all semblance of hilarity at the expense of his faux pas mutates into toxic anxiety as we wait for polite social cues to kick in. Other supporting characters, those accustomed to Norman’s empty enterprises, have little patience for him, such as Harris Yulin and Dan Stevens (playing a mogul and his assistant, respectively). Meanwhile, the only real naive party seems to be Steve Buscemi’s Rabbi Blumenthal, himself devoted to an archaic system and set of beliefs which no longer apply to the way the world works and moves.

Both New York and Israel are presented in sterile, unenticing fashion, landscapes occupied by characters too preoccupied with their own objectives or dilemmas to take note of Norman, except when he’s not where he’s supposed to be. A social blight (a quiet removal from a private party function presents this awkwardness convincingly) until his investment with Eshel pays off and Norman suddenly becomes an enviable somebody in the US-Israeli arena, he tellingly breathes a sigh of relief by comparing the friendship to the act of betting on a horse. And it’s here where our sympathies (if they haven’t already been consumed by irritation) for Norman are compromised—a man who has existed on a social periphery partly because he treats other humans as opportunities for gain.

Cedar, who also wrote the screenplay, creates an impressively dense network of cross-cultural political intrigue, which mostly works because Norman’s own perspective is so obfuscated, and thus maintains an ambience of unease and paranoia. By the time Cedar sets a clear course for its bleak finale, Norman has taken on the aura of a moral fable, but leaving behind a potent residue of complicity and guilt as regards the complex mixed emotions Cedar and Gere are able to conjure.

★★★½/☆☆☆☆☆