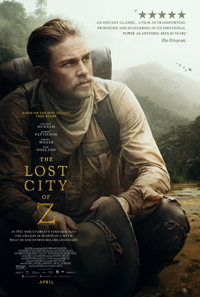

Zed and Buried: Gray’s Period Adventure a Meticulous Throwback of Epic Filmmaking

American auteur James Gray unveils his most provocative film yet with the painstaking, portrait of obsession, The Lost City of Z, an inspired adaptation of the 2009 nonfiction title by David Grann, which charts a British Army Officer’s obsessive hunt for a mythical city in the dense, dangerous jungles of turn-of-the-century Bolivia. Less fascinated with the concept of fortune and glory (for the most part) or action inclined tangents detailing breathless scrapes with danger, Gray focuses intently on the relentless yet sobering ambition of a man who becomes inspired and fascinated by discovering unknown origins, even if it means confirming the superiority of the civilized white race as merely an unfounded urban legend. Even at nearly two-and-a-half hours running time, Gray has chosen selective instances of one man’s two decade adventure, ultimately raising more questions than it answers, as well as conveying a tradition of epic cinema which faded out of American film by the late 1980s. Grandiloquent, methodical, and fascinating, the new direction is becoming for Gray, who masterfully conjures a mysterious period of anticipation, when the world was uncharted and carried unimaginable secrets in its bosom.

American auteur James Gray unveils his most provocative film yet with the painstaking, portrait of obsession, The Lost City of Z, an inspired adaptation of the 2009 nonfiction title by David Grann, which charts a British Army Officer’s obsessive hunt for a mythical city in the dense, dangerous jungles of turn-of-the-century Bolivia. Less fascinated with the concept of fortune and glory (for the most part) or action inclined tangents detailing breathless scrapes with danger, Gray focuses intently on the relentless yet sobering ambition of a man who becomes inspired and fascinated by discovering unknown origins, even if it means confirming the superiority of the civilized white race as merely an unfounded urban legend. Even at nearly two-and-a-half hours running time, Gray has chosen selective instances of one man’s two decade adventure, ultimately raising more questions than it answers, as well as conveying a tradition of epic cinema which faded out of American film by the late 1980s. Grandiloquent, methodical, and fascinating, the new direction is becoming for Gray, who masterfully conjures a mysterious period of anticipation, when the world was uncharted and carried unimaginable secrets in its bosom.

British Army Officer Percy Fawcett (Charlie Hunnam) is dispatched by the National Geographic Society to travel to Bolivia in 1906 as a cartographer and map out the unexplored region. An undecorated officer with the misfortune of belonging to a shamed family name, he sees this as a chance to secure the future for his family, something his wife Nina (Sienna Miller) understands. Securing aide-de-camp Henry Costin (Robert Pattinson), his first expedition whets the man’s appetite for he stumbles upon rumors about an ancient, lost city deep in the jungle, a place no white man has ever been lucky to see. Accounts from several slaves who help guide him along the river plus several artifacts would seem to support this theory. When he returns home, conservative British society is none too pleased to hear about a bunch of ‘savages’ Fawcett claims to be more intelligent and sophisticated than they’d like to hear. Scoffing at his theory of a lost city he has named Zed, Fawcett secures funding to return for another expedition thanks to the support of James Murray (Angus Macfadyen), who insists on coming along and hobbles Fawcett’s mission. Before he’s able to return again, WWI has broken out and Fawcett is forced to the battlefields, where an injury makes him temporarily blind. Years later, it is only through the insistence of his eldest son (Tom Holland) Fawcett ends up back in Bolivia, once again attempting to find the lost city.

Gray often seems fascinated by particular times, places, and periods, often focusing on a triptych of main players whose lives become inextricable interwoven, a protagonist at the apex of a triangle of which the other two points clash. This time around, Gray’s characters are dwarfed by the scope of the narrative rather than steering it, the focus harpooned on the various attempts of Hunnam’s John Fawcett and his attempts to become the master and commander of his fate. We meet him as an undecorated officer in the midst of a hunt, stealing the glory of the kill, which is hardly enough to overcome the shame his father, a drunken gambler, brought to the family name. The unexpected offer from the National Geographic Society leads him unexpectedly to his life’s purpose, something reaffirmed several times, including with a quietly transfixing moment on a WWI battlefield, when a Russian psychic confirms his life’s purpose even after two failed endeavors to find Z.

Remarkably, Gray does not use the film as an opportunity to skewer colonialism, instead focusing on Fawcett’s sincere passion to prove his ignorant English colleagues wrong, by proving the natives as capable of invention as any of their counterparts on the European continent. Selfishly, he knows his discovery will immortalize him and his family name, and the ultimate sacrifice is his family life, though he luckily married an understanding woman who believes in challenging cultural misconceptions (including the role of woman) as much as her husband. The effect, however, of focusing only completely on Hunnam, often makes his sequences with his intimates such as Sienna Miller and Robert Pattinson, seem artificial—although, arguably, this is partially due to the yoke of social mores imposed on a man like Fawcett, who is most alive when experiencing the passion of his adventure. It’s a testament to Gray’s abilities as a director how he manages to morph performers who are sometimes wooden or extraneous into vibrant supporting players, and one need look no further than a warm performance of Miller, an actor who often fades into the background. Likewise, Charlie Hunnam transforms into a surprisingly engaging man of idealism, and (perhaps even to himself) progressive attitudes toward racial others. Pattinson gives a no-frills turn as sidekick Henry Costin, his hirsute army buddy along for the ride.

Despite its arguable lack of grand set pieces, the horrors of the jungle are ever present, whether they be shrunken heads, cannibalized corpses, or a school of terrifying piranhas (who turn out to be the more dangerous predator while Fawcett’s crew is assailed by arrows on a raft). Christopher Spelman crafts an unassuming score, assisted by strands of notable classical composers (echoes of Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring lends a lovely foreboding undertone as Hunnam and Fawcett take their first train out of civilization), and DP Darius Khondji (who reunites with Gray following The Immigrant, but has crafted many an auteur’s notable masterwork, including entries by Fincher, Haneke, Allen, and Jeunet) moves from lush sequences in the rainforest, to browned out battlefields, to anxiety laden English interiors to create an impressive, roving film palette.

Reviewed on February 14 at the 2017 Berlin International Film Festival – Special Screenings Program. 140 Mins.

★★★★/☆☆☆☆☆