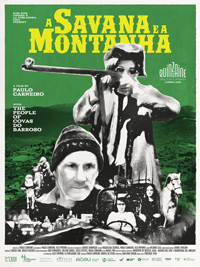

Once Upon a Time in Barroso: Carneiro Speaks Truth to Power

Opening with the gusto of a faded fairy tale, Portuguese filmmaker Paulo Carneiro’s Savanna and the Mountain (A savana e a montanha), which is technically the documentary filmmaker’s narrative debut, aims to shine a light on the shady dealings of a multinational’s mining operation in the tranquil community of Covas do Barroso. Surprisingly, we learn the re-enacted events, all told from the perspective of the local villagers, is an ongoing struggle of the recent past, when the corporation Savanna Resources decided to pursue the creation of lithium quarries, with a broader plan to transform the region. Although this is a recent example of corporate sublimation, Carneiro’s formulation reflects a tale as old as time, though no less frustratingly potent, perhaps made all the more so by utilizing the area’s actual citizens to depict their early rallying as a response to a takeover none of them were consulted about.

Opening with the gusto of a faded fairy tale, Portuguese filmmaker Paulo Carneiro’s Savanna and the Mountain (A savana e a montanha), which is technically the documentary filmmaker’s narrative debut, aims to shine a light on the shady dealings of a multinational’s mining operation in the tranquil community of Covas do Barroso. Surprisingly, we learn the re-enacted events, all told from the perspective of the local villagers, is an ongoing struggle of the recent past, when the corporation Savanna Resources decided to pursue the creation of lithium quarries, with a broader plan to transform the region. Although this is a recent example of corporate sublimation, Carneiro’s formulation reflects a tale as old as time, though no less frustratingly potent, perhaps made all the more so by utilizing the area’s actual citizens to depict their early rallying as a response to a takeover none of them were consulted about.

In the quiet village Covas do Varroso in northern Portugal, the locals finds chaos descending upon them through a series of advertising pamphlets from Savanna Resources announcing the development of lithium quarries in the region. Just prior to this, ominous signs of something wicked on the horizon have the horses behaving skittishly, alarming their handlers. While some members of the community want to believe the corporation’s well-meaning statements regarding revitalizing job creations, most are highly skeptical. Eventually, they decide to take matters into their own hands and bar the company’s representatives from gaining access.

Much like Joshua Oppenheimer’s The Act of Killing (2012) or The Look of Silence (2014), Carneiro channels a particular brand of authenticity and immediacy through the hybridization of documentary and reenactment. The film’s tone mainlines the spirit of rebellion and resistance, with local musical artists channeling this struggle into the realm of folk heroism, collapsing past methods of cultural consumption and remembrance with the present. This conjunction also recalls the revitalization of historical traumas in the adaptation of folk song to film, much like Robert M. Young’s early Chicano classic The Ballad of Gregorio Cortez (1982), starring Edward James Olmos.

But Savanna and the Mountain feels eerily like the real-life version of similar events happening in Ryusuke Hamaguchi’s latest, Evil Does Not Exist (2023), where a quiet community is similarly confronted with the transformation of their region when a luxury tourist camping site moves into and takes over. There’s a sense of levity in Carneiro’s proceedings, usually with the villagers planning, cueing light bickering as they decide who amongst them should be recruited for particular roles in their resistance. In their various clandestine meetings, they are dismayed to realize some of the men hired by the mining company are actually well-meaning, hailing from surrounding villages much like their own, fooled by the corporation’s refrain about the creation of new jobs, as if this automatically correlates to positive change.

Carneiro ends with brief statements about the region’s being deemed a World Agriculture Heritage by the Food & Agriculture Organization of the United Nations in 2018. Ending with a gathering of villagers on their various machines, like the finale of an anachronistic science-fiction film, before he cuts to sounds of off-screen violence, the film rather curtly confirms “No enemies were shot.” But it’s a statement which hangs in the air before the end credits quite ominously, as Savanna and the Mountain is not a film about resolution.

Reviewed on May 18th at the 2024 Cannes Film Festival – Directors’ Fortnight. 77 Mins.

★★½/☆☆☆☆☆