The Spurning Point: Preljocaj Does the Dance Divine with Sensible Debut

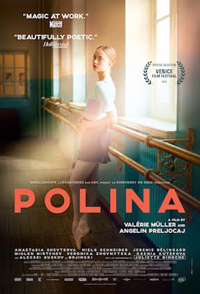

Famed French choreographer Angelin Preljocaj melds his modern rhythms with a classic bildungsroman structure in narrative debut Polina. Playing like a Soviet chip off the block of Dreiser’s Sister Carrie, Preljocaj, who co-directs with his wife Valerie Műller, presents a familiar tale of breaking free from convention in order to find one’s creative voice.

Famed French choreographer Angelin Preljocaj melds his modern rhythms with a classic bildungsroman structure in narrative debut Polina. Playing like a Soviet chip off the block of Dreiser’s Sister Carrie, Preljocaj, who co-directs with his wife Valerie Műller, presents a familiar tale of breaking free from convention in order to find one’s creative voice.

Starring in this high-art intersection of Save the Last Dance (2001) and Flashdance (1983) is Russian dancer Anastasia Shevtsova, who brings a wide-eyed austerity to the titular role of a classically trained ballerina forced to reinvent herself in the wake of rejection and familial tragedy. While its beats are a bit roughhewn and familiar, impressive performance and a prosaic examination of an unyielding profession requiring a surplus of passion even as its practice hemorrhages inventiveness supplies Preljocaj and Muller’s debut collaboration with enough zest to justify a journey to an exquisite denouement.

Training to be a professional ballerina from a tender age, Polina (Anastasia Shevtsova) hones her craft under the tutelage of Bojinksy (Aleksey Guskov), a once controversial choreographer in his native Russia. Eventually, Polina is burned out by his incessant demands, and on the eve of joining the Bolshoi Ballet, she absconds to France for the summer with her boyfriend (Niels Schneider) in hopes to score a part in a production of Snow White for choreographer Liria Elsaj (Juliette Binoche). But her overzealousness and ambition results in her undoing. At a crossroads in Paris, Polina takes as a job as bartender while weighing her options and escaping responsibility. But when she meets Karl (Jeremie Belingard), a man who teaches students dance at a youth center, Polina’s passion is reawakened, and an opportunity for her to display her creativity presents itself.

Polina is adapted from a graphic novel by Bastien Vives, and its early sequences paint a portrait of a rigid Father Russia, wherein the impish young lass is tossed into the perfectionist clutches of Aleksey Guskov’s infamous instructor. While her parents are always treated as a narrative footnote (dad is Georgian and mom is Siberian, a juxtaposition which isn’t further developed), Polina’s estrangement from them also enhances the lack of audience empathy for her—initially, up until the finish line, she’s an inscrutable mixture of disappointed willfulness or an anxious overachiever.

Her impossible to please teacher becomes a pseudo-father figure for Polina, her own invested in vaguely illegal activities (a tense scenario involving “the Afghan Route” looms a bit too prominently in dialogue which never moves beyond the superficial). Her relationship with Bojinksy is a toxic one, however, as evidenced by his troubling paradox to coax her into success and yet tear her down for a lack of ardor. Their dynamic seems to shade Polina into a Whiplash (2014) sort of vibe until she thwarts her advancement with the prestigious Bolshoi Ballet for a chance at contemporary dance in France with Binoche, playing a stand-in for Preljocaj himself.

Both Binoche and the formatting of this segue recalls Olivier Assayas’ 2008 documentary Eldorado which detailed Preljocaj’s mounting of a ballet set to Karlheinz Stockhausen. As usual, Binoche balances captivating screen presence in what could otherwise have been a stepping stone to the inevitable third act (the best sequence courtesy of Shevtsova voyeuristically observing Binoche as she dances by herself joyfully and ecstatically, an emotion she herself hasn’t been able to conjure at all).

If twin instructors provide parameters for Polina’s development, so do a pair of love interests, including Niels Schneider (of Xavier Dolan’s Heartbeats, 2009), and the more expressive yet completely convenient Jeremie Belingard (a noted dancer with the Ballet de L’Opera de Paris), who represents the sort of Patrick Swayze figure to her Jennifer Grey. Together, all of them feel like supporting figures which guide Polina to her crowning achievement, which becomes the pièce de résistance of the film as projected by Preljocaj and Műller (and, again, feels like the finale of the Assayas documentary in its presentation of a major creative achievement we’ve seen the workshop process of).

While some of its more cliched elements could have been excised in honor of a more efficient running time (a late staged training montage feels as hoary similar sequences from any of its American cousins), the final moments of Polina are rewarding and worth the development of a character demanding requisite time and space to discover her own voice.

★★★/☆☆☆☆☆