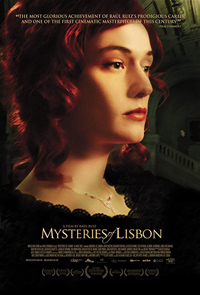

Epic in length but not in dramatic punch, Raúl Ruiz‘s plodding period literary adaptation Mysteries of Lisbon sells itself as a highbrow soap opera but is mainly just a glorified video installation piece. In theory, the 18th century-set plot (taken from Camilo Castelo Branco’s novel) full of lurid intrigues, forbidden loves, piracy, betrayals, murders and secret identities should make for an engrossing narrative puzzle. But as flashbacks pile up and backstories spiral inward, audience yawns spill out. Ruiz seems to be experimenting with elasticized melodrama, with each plot point stretched to its limit, each big revelation squeezing glacially to the surface — and usually falling flat on arrival. That’s because for all of its convolution, the story is just a perfunctory excuse for Ruiz to show off a lifetime’s collection of didactic filmmaking techniques.

Epic in length but not in dramatic punch, Raúl Ruiz‘s plodding period literary adaptation Mysteries of Lisbon sells itself as a highbrow soap opera but is mainly just a glorified video installation piece. In theory, the 18th century-set plot (taken from Camilo Castelo Branco’s novel) full of lurid intrigues, forbidden loves, piracy, betrayals, murders and secret identities should make for an engrossing narrative puzzle. But as flashbacks pile up and backstories spiral inward, audience yawns spill out. Ruiz seems to be experimenting with elasticized melodrama, with each plot point stretched to its limit, each big revelation squeezing glacially to the surface — and usually falling flat on arrival. That’s because for all of its convolution, the story is just a perfunctory excuse for Ruiz to show off a lifetime’s collection of didactic filmmaking techniques.

Andre Szankowski’s classical, painterly lighting and the impeccably detailed production design are both gripped firmly between the quotation marks of the harsh crispness of the HD image, which serves as a barrier to the audience’s full immersion into the story. Though this is perfectly in line with Ruiz’s Brechtian program — he continually punctuates the goings-on with shots of character cut-outs on a stage proscenium diorama — the nearly 4½ hour running time is enervatingly long for what ultimately amounts to a self-evident formal exercise.

In 18th century Lisbon, orphan boy Joao searches for his real identity, and aided by the heartfelt ministrations of Catholic priest Father Dinis, stumbles upon a vast intertwining web of stories where everyone has a dirty secret and no one is what they seem. Groveling henchmen transform into wealthy noblemen; ladies move in and out of the convent not because of the demands of the spirit, but those of the pocketbook; the past is alive in the present; everything might just be a dream. The anchoring character is that of the priest, Father Dinis (an appropriately weathered Adriano Luz). He is a man with a history of myriad identities — wandering gypsy, aristocratic gentleman — who has now consigned himself to the burden of trying to shepherd faulty humans through their various tragedies and comedies.

Viewers sitting through Mysteries of Lisbon might relate. They might also risk the charge of intellectual unrefinement by wishing that Ruiz had just rolled up his sleeves and enthusiastically engaged with his rich source material. Instead, the relentless emphasis on theatricality and artifice feels aesthetically over-rehearsed. Perhaps the academic Ruiz intended the movie as an instructional primer in self-conscious formalism for a broader European TV audience (the movie was initially made for Portuguese TV), but he isn’t breaking any news to his regular niche arthouse movie audience, only helping to buttress their elitist self-presumptions.

Despite the daunting intellectualism behind it — or perhaps because of it — Mysteries of Lisbon falls way short of the audacious peaks set by other cinematic literary adaptations. On occasion it visually references Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon, but without capturing the underlying deterministic ethos of that movie, in which the deliberate pacing was a tangible expression of the irresistible machine of Fate — or maybe just the social order — grinding the human figures towards their destinies. Nor is Ruiz able to find a compatibility between intellectual rigor and emotional power, as R.W. Fassbinder did in his adaptation of the 19th century German novel Effi Briest, where he jarringly emphasizes the negative spaces of the melodrama, the holes between the histrionics, while still creating something riveting and personal. Fassbinder’s effort was an act of subversion against the safe, status quo-reinforcing comforts of cultural heritage; in contrast, Ruiz makes this movie as if he’s looking to get a good grade on a film theory class final.

The admirably unerring uniformity of meticulous cinematography and precise mise-en-scene has an accumulated effect of numbing the viewer until one moment when a unusual alienation effect comes into play in the form of a single exterior shot of a harbor. The image is slightly blurred and uncomposed, while the camera seems unframed, as if it had been mistakenly left running. In this one shot there is life — distracting, unexpected, awry and beautiful. Then Ruiz cuts, and the modernist marathon continues.

★★½/☆☆☆☆☆