The Big Empty: Fgaier Crash Lands with Sentimental Drivel

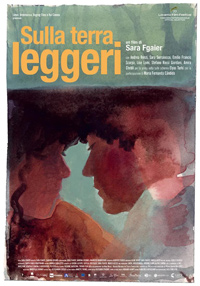

For her directorial debut Weightless (Sulla terra leggeri), film editor Sara Fgaier opens her narrative with a passage from Julian Barnes’ Levels of Life, a 2013 memoir exploring grief, which ends with the line, “when we soar, we can also crash.” Although aviation is also a tangential detail to her narrative, there’s never a moment when anything really soars in what ends up being a sappy exploration of reclaiming memories of passionate love between characters who couldn’t be less interesting if they tried. The passage, much like the film’s title, ironically ends up being ripe for substantial punning, considering its a formidably inconsequential offering as either an emotional or amorous human experience.

For her directorial debut Weightless (Sulla terra leggeri), film editor Sara Fgaier opens her narrative with a passage from Julian Barnes’ Levels of Life, a 2013 memoir exploring grief, which ends with the line, “when we soar, we can also crash.” Although aviation is also a tangential detail to her narrative, there’s never a moment when anything really soars in what ends up being a sappy exploration of reclaiming memories of passionate love between characters who couldn’t be less interesting if they tried. The passage, much like the film’s title, ironically ends up being ripe for substantial punning, considering its a formidably inconsequential offering as either an emotional or amorous human experience.

Gian (Andrea Renzi) has developed grief-induced amnesia following the death of his wife Leila, to the degree where he doesn’t even recognize his adult daughter, Miriam (Sara Serraiocco). As Miriam moves in to care for her father, whose work as a professor of ethnomusicology is also disrupted by his memory spasm, it seems the only helpful remedy is the unearthing of Gian’s diaries, particularly the documentation of his fateful meeting as a young man (Stefano Rossi Giordani) with Leila (Amira Chebli), an aspiring aerialist. Lost in the throes of memory lane, his reconnection to the past brings him back to the present.

Although Weightless is extensively disappointing as a narrative feature considering Fgaier’s impressive filmography as an editor, there remains evidence of her particular forte, visually speaking. Sharing editing credit with Enrica Gatto and Aline Herve, the film comes to visual life in various montages of archival footage, which were also arguably certain strengths of the early titles Fgaier edited for Pietro Marcello, such as The Mouth of the Wolf (2009) and Lost and Beautiful (2015). Likewise, the film’s diegetic music, which includes mixtures of classical, including Handel, and vintage American pop, such as Tommy James and the Shondell’s “Crimson and Clover” (though the celebration of love this is supposed to enhance doesn’t come close to justifying the use of the track).

The youthful, overnight fireworks transpiring in the flashbacks between Gian and Leila are trying to convey something along the lines of Poe’s “Annabel Lee,” in the hyperbolic excess of “But we loved with a love that was more than love—.” The energy actually conjured feels painfully commonplace, and it’s never clear how Gian’s reclamation of these memories through the excavation of his diaries is supposedly regenerating his return to reality. Fgaier’s attempts to process the pain of Leila’s reckless abuse of their connection are equally sleepy, returning as she does to Gian a year later than expected in their youth, when he’s supposedly fallen in love with the equally dull Anna. Passages of dialogue in these moments are greased with the kind of hokum found in dime store romance novels. “I believe I now understand what bliss means,” Gian moans as he clutches Leila, staring up into the sky.

As saccharine as Gian’s mundane flashbacks tend to me, they’re nothing compared to the contrived drama of his present. As his daughter Miriam, mooning about like a despondent vampire, Sara Serraiocco is required to endure endless hand wringing about daddy’s lovelorn memory loss. This is eventually somewhat resolved through Gian’s supposed reconciliation with the torrential emotions he’s compartmentalized, but at the end of this trite mind journey, it’s unclear what Fgaier intended for us to feel for this tiresome family whose main issues, passed down generationally, seem to revolve around not being able to control the behaviors of those they want to stay connected to.

Reviewed on August 13th at the 2024 Locarno Film Festival (77th edition) — Concorso Internazionale section. 94 Mins.

★½/☆☆☆☆☆