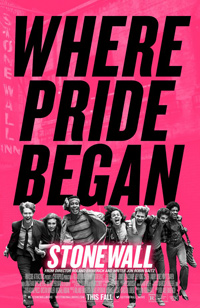

Hole in the Wall: Emmerich Butchers Historical Moment with Whitewashed Overcoat

On June 28, 1969, a group of gay men and women took a stand against police brutality following a raid on the Stonewall Inn, a bar in the Greenwich Village neighborhood of Manhattan. The event sparked a series of violent demonstrations by members of the LGBT community around the period, and it’s considered the birth of the gay liberation movement. In the decades since, lingering urban legends have haunted the events (such as a grieving community motivated specifically over the recent loss of Judy Garland) surrounding the stand taken at a mafia owned bar raided regularly by police, whose owner cared little about the safety or health of his patrons either way. A significant moment in the ensuing decades-long battle for LGBT rights in the United States certainly marks it as deserving of its own cinematic reenactment. However, action film director Roland Emmerich (Independence Day; White House Down), filming the New York set tale in the gay village of Montreal, takes a singularly significant moment in time and brutally stuffs it into a melodramatic narrative centered on a white male protagonist. Bereft of nuance and subtlety, this is a stupendously mishandled treatment of potent material and a sacrilege to the memory of those whose bravery it siphons off into a glossy bildungsroman of some imaginary white hero.

On June 28, 1969, a group of gay men and women took a stand against police brutality following a raid on the Stonewall Inn, a bar in the Greenwich Village neighborhood of Manhattan. The event sparked a series of violent demonstrations by members of the LGBT community around the period, and it’s considered the birth of the gay liberation movement. In the decades since, lingering urban legends have haunted the events (such as a grieving community motivated specifically over the recent loss of Judy Garland) surrounding the stand taken at a mafia owned bar raided regularly by police, whose owner cared little about the safety or health of his patrons either way. A significant moment in the ensuing decades-long battle for LGBT rights in the United States certainly marks it as deserving of its own cinematic reenactment. However, action film director Roland Emmerich (Independence Day; White House Down), filming the New York set tale in the gay village of Montreal, takes a singularly significant moment in time and brutally stuffs it into a melodramatic narrative centered on a white male protagonist. Bereft of nuance and subtlety, this is a stupendously mishandled treatment of potent material and a sacrilege to the memory of those whose bravery it siphons off into a glossy bildungsroman of some imaginary white hero.

In 1969 Kansas, high school football player Danny (Jeremy Irvine) is outed when some of his teammates discover him in a delicate position with his secret lover, fellow ballplayer Joe (Karl Glusman of Gaspar Noe’s Love). Running away to New York City to avoid being sent for corrective treatment by his homophobic father, Danny stumbles upon the vibrant and unabashedly queer Greenwich Village neighborhood where he catches the eye of Ray (Jonny Beauchamp). Sprightly and energetic, Ray, whose drag name is Ramona, inducts Danny into the ways of the street, where drugs and prostitution reign as a means to support oneself day to day. While Ray clearly fancies Danny, the young Midwesterner is swept away by the older Trevor (Jonathan Rhys Meyers) after they meet at the mafia run gay bar Stonewall Inn, run by Ed (Ron Perlman), a man known for pimping out young white hustlers who come into the bar. While Trevor attempts to lure Danny into the ranks of the famed Mattachine Society, the famed early gay rights organization practicing peaceful resistance, Danny soon learns he’s unable to maintain a passive voice amidst the hatred surrounding them at every turn.

Emmerich opens with black and white typewriter font announcing the infamous date of the riots, then lists a multitude of factual information as concerns the resentment towards the LGBT community, citing laws, stipulations, and consequences for being gay (unfortunately, this layout makes it seem like all of these things were specific to the day in question, 6/28/69). But this is the first of many corners cut.

The film’s greatest folly is framing the events through the perspective of a white ambassador, here the Midwestern cipher played by Jeremy Irvine in a tonally awkward performance. Irvine, first seen in Spielberg’s War Horse (2011) is in after-school-special mode, moving into an increasingly hysterical, over-the-top register as the film wears on.

Though no concrete, definitive evidence actually proves who the first person was ‘exactly’ to throw the first brick, it’s long been asserted that drag queens, as well as black and transgendered men, and a healthy dose of lesbians were responsible and present in this very mixed, very diverse group of rioters.

Focusing exclusively on a make believe white, and notably masculine male while relegating a known entity like Marsha P. Johnson to the utmost periphery (as portrayed by Otoja Abit in a rather clownish performance) seems in poor taste. Likewise, the infrequent use of other black characters, such as the drag queen Cong played by Vladimir Alexis (reminiscent of 70s era Antonio Fargas) is another broad stroke stock character, not unlike a gaggle of other supporting players here, with even Caleb Landry Jones underwhelmingly utilized.

If there’s anyone worth noting in the cast, it’s an energetic and endearing performance from Jonny Beauchamp as Danny’s doting friend. Emmerich and screenwriter Jon Robin Baitz present their friendship via a series of troubling assumptions concerning racial divisions and attraction within the community as generalized assumption. Danny’s romantic entanglements revolve solely around other white characters, ones who look and engage in gender dynamics awfully similar to his own (Jonathan Rhys Meyers, for instance) while his muted friendship for Ray/Ramona is explained away by another white cipher who gives a monologue about people you can only ever love as a friend. This all reads as rather troubling coding about the superior and innate beauty of not just masculinity but whiteness, and certainly aren’t things we should be distracted by in a film concerning the Stonewall riots.

But even with these appalling missteps, one can’t overlook the increasingly hammy scenario glazing over an important historical moment. This is a tale worth telling and documenting, as has been done in the past thanks to the 1984 documentary Before Stonewall (and it’s 1999 follow-up After Stonewall), plus a 1995 reenactment bearing the same title from director Nigel Finch. Considering today’s more enlightened social attitudes, it’s certainly a chapter worth revisiting.

The Stonewall Riots represent a moment in time when a disenfranchised community banded together in rebellious retaliation, and was certainly not the impetus of white, heteronormative values the community has since adopted since, where tolerance and acceptance from the majority has resulted in a foregone assimilation of these traits. But whatever the case, Roland Emmerich’s version is not equipped with the right elements to successfully convey the early days of gay liberation. Frankly, we deserve better.

Reviewed on September 18th at the 2015 Toronto International Film Festival – Galas Program. 129 Mins.

★/☆☆☆☆☆