What Costume Shall the Poor Girl Wear?: Nicchiarelli Knits Stellar Portrait of a Troubled Artist

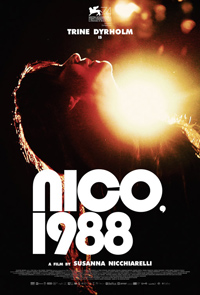

“I’ve been at the bottom and I’ve been at the top—both are empty,” growls Trine Dyrholm as a surly Christa Paffgen aka Nico, the famed chanteuse who sang lead vocals on three of The Velvet Underground’s most beloved hits in the late 1960s. Italian director Susanna Nicchiarelli examines the last year of the troubled singer’s life in her third feature, Nico, 1988, which allows Danish actress Dyrholm to let loose as the frustrated and frustrating German born star, living in Manchester, England and embarking on what would be her final tour through Communist infused Europe.

“I’ve been at the bottom and I’ve been at the top—both are empty,” growls Trine Dyrholm as a surly Christa Paffgen aka Nico, the famed chanteuse who sang lead vocals on three of The Velvet Underground’s most beloved hits in the late 1960s. Italian director Susanna Nicchiarelli examines the last year of the troubled singer’s life in her third feature, Nico, 1988, which allows Danish actress Dyrholm to let loose as the frustrated and frustrating German born star, living in Manchester, England and embarking on what would be her final tour through Communist infused Europe.

Singing her own covers of several of Nico’s most notable standards, Dyrholm descends upon the screen like a flailing dragon from a bygone era (she won a special acting prize out of the Venice Horizons sidebar). Endlessly defined by her associations with iconic figures of the 1960s and 70s rather than her own artistic merits, Nicchiarelli presents a portrait of woman whose creative groove was revived at the end of an era which already considered her a relic, battling addiction and familial woes until her unexpected death in Ibiza in 1988.

Dyrholm provides an interpretation of the aging Christa Paffgen aka Nico, who at nearly fifty years of age finds herself living alone in Manchester, England while her son Ari (Sandor Funtek) has been confined to a hospital in Paris after a deadly overdose. Her new manager, Richard (John Gordon Sinclair) convinces her to go on tour across Europe to promote her latest album. Joined by her son after his release, Nico’s troubles never seem far behind as she struggles in vain to negotiate her career without being defined by her glamorous past.

The defeat of Berlin, as it’s bombed to rubble in the waning days of WWII provides the film with its quietly effusive sense of doom and foreboding. A young Christa Paffgen and her mother observe the eerily beautiful consuming flames on the horizon form the safety of Spreewald forest in the film’s opening moments, a formative experience which will come to haunt her as an adult. Nicchiarelli chooses to present Nico’s potential anti-Semitism as merely a politically incorrect way of approaching an uncomfortable history, usually observed through her relationship with manager Richard, whose Jewishness is a talking point. Likewise, Nicchiarelli’s screenplay plays with the cultish mysteriousness which surrounds the singer, such as her affair with French actor Alain Delon, who she claimed was the father of Ari, a child he never recognized (but who was formally adopted by Delon’s parents and is not formally named here). Rumors of her affair with Brian Jones of The Rolling Stones, likewise, is a fragmented whisper from her fractured and prolific romantic past.

If squabbles amongst the bandmates are neither here nor there, whether they be conflicted liaisons between Richard and his helpmate played by Karina Fernandez, or a doomed romance between a heroin addicted guitarist and a bleeding-heart violinist played by Anamaria Marinca, (the 4 Months, 3 Weeks, and 2 Days actress shunted into yet another superfluous supporting role), it hardly matters because they’re merely breaks between the next Dyrholm dose.

Transfixing us with her cover of “All Tomorrow’s Parties” and giving a rousing illegal concert in Prague as she performs “My Heart is Empty” while suffering heroin withdrawal, Dyrholm’s energy festoons Nico, 1988 with the formidably necessary presence to make this bio format relevant. A boxy 1.85 aspect ratio only seems to add the square, mediocrity Nico is trying to break away from, and if she isn’t giving a haunting performance (it’s easy to see where Bjork found her inspiration), then there are a handful of withering interviews for her to sharpen her claws upon.

In exchanges with her emotionally unstable son, Ari, Dyrholm takes on the heightened grandeur of a cursed gothic creature, like a witch or vampire cursed to deal with the Sisyphean onslaught of her progeny’s anguish. It’s an immensely impressive transformation from Dyrholm, an accomplished star who is rarely this gritty and coarse. If the other figures of Nico, 1988 pale almost unfavorably by comparison it’s because she simply gobbles them up—she’s larger than life and disinterested in the banalities of day-to-day existence.

Sadly, Nicchiarelli’s limited scope bypasses Nico’s Warhol days (despite some creative flashback montages which appear as if behind her eyes while performing) and her extensive 1970s period as a muse for Philippe Garrel. Instead, Nico, 1988 unfolds like a vibrantly photographed vivisection of late 1980s Communist Europe, assisted by some expert visual compositions from DP Crystel Fournier (best known for her trio of Celine Sciamma titles Water Lilies, Tomboy, and Girlhood).

★★★½/☆☆☆☆☆