Once Upon a Time in Australia: Thornton’s Western-inspired Saga of Violent Racial Discrimination

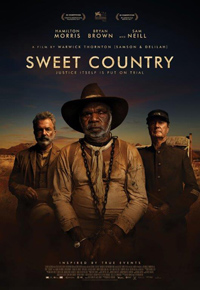

Racial tensions in Australian society are given historic treatment in the outback-Western Sweet Country, Warwick Thornton’s follow-up to his immensely successful debut Samson & Delilah, which received the Camera d’Or in Cannes Film Festival in 2009. Set in the frontier stations sparsely populating the country’s vast Northern Territories of the 1920s, it has the epic dimension of a folk legend, though inspired by real events in its tale of social injustice. At its heart are the anguish of the native Aboriginal people and their victimization in the hands of white folk, whose invasion of sacred lands and abuse of labor is laid bare by Thornton’s impressive and visual storytelling.

Racial tensions in Australian society are given historic treatment in the outback-Western Sweet Country, Warwick Thornton’s follow-up to his immensely successful debut Samson & Delilah, which received the Camera d’Or in Cannes Film Festival in 2009. Set in the frontier stations sparsely populating the country’s vast Northern Territories of the 1920s, it has the epic dimension of a folk legend, though inspired by real events in its tale of social injustice. At its heart are the anguish of the native Aboriginal people and their victimization in the hands of white folk, whose invasion of sacred lands and abuse of labor is laid bare by Thornton’s impressive and visual storytelling.

The pious Christian Fred Smith (Sam Neill) runs a remote cattle station with the help of his indigenous right hand man Sam Kelly (Hamilton Morris). Located relatively nearby are two other ranchers, Mick Kennedy (Thomas M. Wright) and the newcomer Harry March (Ewen Leslie) visibly suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder having serviced in the First World War. Both are racist bigots, though perhaps Harry is more cruel and sadistic in his treatment of “blackstock” – his own words, when asking Fred if he could borrow (read exploit) help to upgrade his cattle yard. Fred sees no racial divide for religious reasons, but unwittingly agrees to hand over Sam for work, during which Harry rapes Sam’s wife Lizzie (Natassia Gorey Furber) in a deeply uncomfortable scene shot through a virtuoso camera movement revolving around itself.

Oblivious to what happened, Sam goes back to his station. But Harry continues to abuse his privilege and acquire another round of free labor from Mick, this time the chalky-bearded elder Archie (Gibson John) and Mick’s mixed-race son Philomac (played by twins Tremayne and Trevon Doolan), whose youthful rebellion impels Harry to lock him up in chains. Escaping Harry’s menace, Philomac takes refuge at a shack near Sam, while Fred is away in town for business. Soon Harry’s alcoholic rage escalates into a shoot-out, in which Sam fires in self-defense. Witnessing the event as a bystander, Archie provides an eloquent summary: “You just a killed a white fella. You’re in for it now.”

With this premise, the film moves into its second act, where a posse rounded up by Sergeant Fletcher (Bryan Brown) pursues Sam and Lizzie across the arid territories of Australia’s outback. Referencing the film’s ironic title, Thornton is careful to picture the couple on the run dwarfed by vivid vistas of tribal lands, culminating in a hallucinogenic confrontation between Sam and Fletcher in flat salt lands. The native characters are drawn with boundless dignity and performed with grace by non-professional Aboriginal actors – indeed, Morris’s valiant gait and resistance to racism is in stark contrast to other iconic Western stars, while Philomac’s ambiguous insurgency is but an enduring reminder of the legacy of systemic racism.

While much of the film’s screenplay, penned by Steven McGregor and David Tranter, follows a linear structure, there are elliptic editing inserts – rapid flashbacks and foreshadows that instill a lyrical, poetic tone, giving force to the brutal intolerance sweeping Australia’s history. To be sure, this isn’t the manifest destiny so entrenched in the imagination of the American West, but the evocative landscapes nonetheless represent an unspoiled, savage mythology of a land that once existed – and one that is gradually transformed by exploitative narrow-mindedness.

Sweet Country takes its cue from one of the biggest evils of human nature – a story that has been told countless times and in different cultural contexts, though no less compelling here as institutionalized white supremacy leaves indigenous populations in extraordinary poverty, disadvantage and abuse. Such political realism was central to Thornton’s first project, but here he injects a sense of pathos to his characters and riveting story.

Reviewed on October 19th at the 2017 BFI London Film Festival. 110mins

★★★★/☆☆☆☆☆