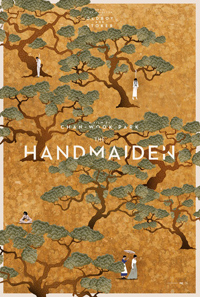

Women in Revolt: Chan-wook’s Sumptuous Period Drama Wrestles with Romance, Revenge

Following his 2013 English language debut, Stoker, South Korean auteur Park Chan-wook returns to his homeland and a familiar examination on vengeful desires with elegant period piece, The Handmaiden. Loosely based on Welsh writer Sarah Waters’ novel Fingersmith (which was adapted into a notable 2005 television miniseries), Chan-wook relocates the historical crime narrative from Victorian England to 1930s Korea, when the country was subjected to Japanese rule. As visually elegant and sumptuously realized as any of the titles from the director’s famed Revenge Trilogy (Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance; Oldboy; Lady Vengeance), the erotically tinged thriller is perhaps a bit more superficial in its mounting luridness, comprised of three separate segments meant to bolster the characterizations of its two leading ladies while also prolonging significant (and arguably ludicrous) reveals. Despite these minor squabbles, this entertaining potboiler manages to satisfy those in the mood for a historically compelling escapist yarn.

Following his 2013 English language debut, Stoker, South Korean auteur Park Chan-wook returns to his homeland and a familiar examination on vengeful desires with elegant period piece, The Handmaiden. Loosely based on Welsh writer Sarah Waters’ novel Fingersmith (which was adapted into a notable 2005 television miniseries), Chan-wook relocates the historical crime narrative from Victorian England to 1930s Korea, when the country was subjected to Japanese rule. As visually elegant and sumptuously realized as any of the titles from the director’s famed Revenge Trilogy (Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance; Oldboy; Lady Vengeance), the erotically tinged thriller is perhaps a bit more superficial in its mounting luridness, comprised of three separate segments meant to bolster the characterizations of its two leading ladies while also prolonging significant (and arguably ludicrous) reveals. Despite these minor squabbles, this entertaining potboiler manages to satisfy those in the mood for a historically compelling escapist yarn.

Opening this narrative triptych is orphan girl Nam Sook-hee (Kim Tae-ri), raised in Japanese occupied 1930s Korea by human trafficker Boksun, selling unwanted Korean babies to unwitting Japanese parents. When a dashing Korean artist (Ha Hung-woo) swoops in with a complicated plot to pose as Japanese Count Fujiwara, he requires a cunning handmaiden in a devious plot. Japanese heiress Lady Hideko (Kim Min-hee) resides under a repressed stewardship to her Korean uncle Kouzuki (Cho Jin-woong) in his dizzying colonial estate, which has three distinct architectural styles. The old man is a sexual deviant and has been inappropriately involving his niece in his decadent sexual antics since she was a child, throughout her traumatic education with a depressed aunt (Moon So-ri, in a brief, morbid role). Fujiwara plans to seduce Hideko, elope with her, and have her committed to an insane asylum with the aid of Sook-hee. But he doesn’t factor on the attraction both women eventually feel towards one another.

What’s most lamentable about Chan-wook’s version is the film’s inability to garner much sympathy for Sook-hee or Hideko, their rebellious agency muted by the film’s prolonged, magisterial weight and the dual sublimation of culture and gender dynamics at play. Interestingly, the film’s blatant heterosexual representations all present women as mere playthings for men, who are either cartoonishly perverse (Jin-woong’s Kouzuki) or the usual brand of exaggerated virility (Jung-woo’s Fujiwara). While we’re led to believe in the growing attraction between the women based on several titillating sexual encounters, where penetration and carnal knowledge are presented with hedonistic glee, the glossy production design and Chung Chung-hoon’s phenomenal framing create more voyeuristic tension than believable chemistry between the women. Of the two, the scrappy newcomer Kim Tae-ri comes across as the likeable underdog, allowed comedic asides thanks to her foul language and initial misanthropic tendencies as a born and bred hustler.

As the Japanese heiress, Kim Min-hee (of Hong Sang-soo’s Right Now, Wrong Then) is presented like a vintage portrait of icy, decadent Euro trash, nearly vampiric in her soulless existence as a calculating woman with her own ruthless plan to gain control of her destiny. Composer Jo Yeong-wook returns to collaborate with Chan-wook, but the rousing emotions suggested by the score often feel at odds with the narrative’s devious complications. Their enduring romance is problematic—their connection may afford them both a chance at agency, but what percentage is opportunistic versus sincere is questionable, which perhaps provides Chan-wook’s film with its most relevant examination of vengeance to date as an all-consuming, ruinous predicament.

Although a slightly more condensed version of events might have assisted in streamlining The Handmaiden’s fluctuating, sometimes cumbersome tonal shifts between the first two chapters, Chan-wook brings this curious romantic revenge melodrama to a satisfying crescendo in the third act, where other returning motifs (this time around, a squirming octopus peripherally recalls Kaneto Shindo’s Edo Porn, 1981) and a grisly scene of torture provide the delirious backdrop for two women playing with the notions of inherent fluidity in sexuality, gender, and cultural appropriation.

★★★½/☆☆☆☆☆