Behind Every Great War Is a Great Story: Szasz’s Captivating, Grotesque Portrait of Life During Wartime

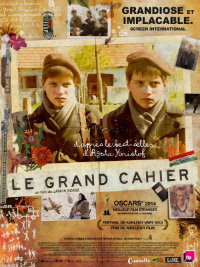

World War II takes on the ambience of an exquisitely grim fairy tale in Hungarian filmmaker Janos Szasz’s The Notebook, based on the famed novel by Agota Kristof. Reuniting the director with Danish star Ulrich Thomsen, who starred in Szasz’s last film, Opium: Diary of a Madwoman (2007), it’s a strikingly photographed, pervasively bewitching account of adolescent twin boys and their development into (mostly) apathetic killing machines due to the inhumane conditions of wartime. Winning the top prize at the Karlovy Vary Film Festival in 2013, the infrequently working Szasz (also a veteran stage director) is a name ripe for rediscovery, heretofore best known for his 1994 film, Woyzeck (the stage play that would also provide the basis for Herzog’s 1979 version).

World War II takes on the ambience of an exquisitely grim fairy tale in Hungarian filmmaker Janos Szasz’s The Notebook, based on the famed novel by Agota Kristof. Reuniting the director with Danish star Ulrich Thomsen, who starred in Szasz’s last film, Opium: Diary of a Madwoman (2007), it’s a strikingly photographed, pervasively bewitching account of adolescent twin boys and their development into (mostly) apathetic killing machines due to the inhumane conditions of wartime. Winning the top prize at the Karlovy Vary Film Festival in 2013, the infrequently working Szasz (also a veteran stage director) is a name ripe for rediscovery, heretofore best known for his 1994 film, Woyzeck (the stage play that would also provide the basis for Herzog’s 1979 version).

Nearing the end of WWII, a privileged father (Ulrich Matthes) decides that while he’s called to join the front, his twin sons (Andras and Laszlo Gyemant) are too conspicuous to remain without his protection. He gives them a notebook and charges them with writing down everything that happens to them so that when they are reunited as a family, they can experience the time lost. As cities are being bombed in air raids, their mother (Gyongyver Bognar) takes them to a small village near the Hungarian border children so that they may live with her estranged mother (Piroska Molnar), with whom she hasn’t corresponded in nearly twenty years. An unsightly troll of a woman, who the villagers refer to as ‘the witch,’ it’s apparent why mom and daughter haven’t been close. Reluctantly, the old woman agrees to take the children, whereby she begins to rule them with a cruel, iron fist. It’s not long before the boys formulate their own ways to deal with the pain and misery of their new existence.

Referred to as One and the Other, twin actors Andras and Laszlo Gyemant are the unfortunate weak points in The Notebook. Their performances are one note, the transgression from privileged, spoiled children to browbeaten, cold blooded killers is hardly depicted with any sort of emotional range by the twins, who seem either vacant or surly, with nary a modulated expression in-between. Likewise, their unchanging hairstyle is a distraction and they appear too well kept considering the undesirable conditions they’re placed in for so long.

Making up for their lack is an excellent performance from actress Piroska Molnar, a well-known Hungarian performer perhaps best known to US cineastes for her appearance in Gyorgy Palfi’s Taxidermia (she also appears in his latest film, Free Fall). Here, she’s an evil ogre that transforms from a hateful caretaker to begrudging guardian. Cruel and abusive, she helps craft the boys into the rabid young beings they become, though their relationship changes in surprising ways. As the boys willfully torture themselves to train themselves against pain and wipeout any semblance of human emotion, they directly signify the dissociative effect of war, eventually making the titular record of their experiences a cookbook for evil merely than an account of depravity.

Szasz employs Christian Berger, the regular DP for Michael Haneke (The Piano Teacher; The White Ribbon; Cache), and The Notebook’s greatest strengths are its austere visual frames—it’s a magnificent looking film to get lost in. A foreboding buzz promises an ever threatening violence, and danger seems to lurk in the corners of the frame at nearly every turn. Szasz refreshingly addresses the weird and dire aspects of sexuality that transpires during wartime to unflinching effect.

Thomsen’s pedophilic tendencies are obvious enough, an serve as an actual asset to the boys’ survival. But his casting is even more significant if you recall The Celebration (1998). An awkward sexual encounter with the maid played by Diana Kiss is also memorable, as is her eventual demise. All of the characters are known only as their occupation or role in the scheme of the world and/or to the boys’ existence. It is perhaps the most apt way that Szasz conveys the reductive, dehumanizing effect war has on all in its wake.

★★★½/☆☆☆☆☆