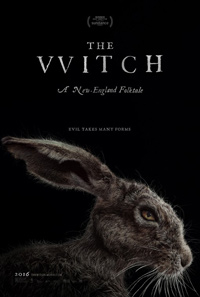

Better the Devil You Know: Eggers’ Debut Marinates with Menace

Easily the most profoundly unnerving film to play at the 2015 Sundance Film Festival, the directorial debut of Robert Eggers is a historical horror film set in 1630 New England, predating the infamous Salem Witch Trials, one of this young country’s earliest grotesque evil chapters. But unlike, say, the dramatic sensation of Arthur Miller’s The Crucible, Eggers’ makes The Witch an odd mixture of fanatical religious paranoia and actual supernatural horror, which creates a fascinating, successful hybrid. Much has been made of the film’s close attention to period detail, enriching the climate as the film slowly tightens into a constricted trap, but impressive performances and just the right touch of the otherworldly make this infectiously effective.

Easily the most profoundly unnerving film to play at the 2015 Sundance Film Festival, the directorial debut of Robert Eggers is a historical horror film set in 1630 New England, predating the infamous Salem Witch Trials, one of this young country’s earliest grotesque evil chapters. But unlike, say, the dramatic sensation of Arthur Miller’s The Crucible, Eggers’ makes The Witch an odd mixture of fanatical religious paranoia and actual supernatural horror, which creates a fascinating, successful hybrid. Much has been made of the film’s close attention to period detail, enriching the climate as the film slowly tightens into a constricted trap, but impressive performances and just the right touch of the otherworldly make this infectiously effective.

Opening with a close-up of Thomasin (Anya Taylor-Joy) in her Sunday best, we find her father William (Ralph Ineson) facing some sort of religiously motivated community trial regarding his particular beliefs. Unwilling to adhere to the norms of the plantation, he’s banished, along with his family, including wife Katherine (Kate Dickey), and four younger children, Caleb (Harvey Scrimshaw), twins Jonas (Lucas Dawson) and Mercy (Ellie Grainger) and infant Samuel. They relocate to an isolated farm at the edge of a foreboding forest, and it’s not long before Samuel gets snatched by a preternatural presence one afternoon under Thomasin’s watch. We witness the chilling fate of baby Sam, but the family is left to wonder, their religion dictating that the baby’s soul has gone to hell because he wasn’t baptized. Since William’s farming and hunting skills are poor, the family seems destined for a harsh winter, but tensions between Thomasin and other females in the household quickly causes further disintegration. A tipping point is reached when Caleb also disappears, returning naked, babbling incoherently.

Inordinately simple, The Witch successfully still manages an impressive chokehold as religious paranoia turns family members against one another, enabling the insidious force to wreak havoc. Ralph Ineson makes an imperious impression, while Scottish actress Kate Dickey is as astringent as she is prone to hysteria. Eggers’ tends to prize the perspective of Thomasin, a girl that’s, shall we say, left without many options. Anya Taylor-Joy, recalling the willowy willpower of Mia Wasikowska, proves to be a great find. But where Eggers’ truly gains ambience is from Jarin Blaschke’s excellent cinematography, capturing the presence of the encroaching forest with beautiful alacrity—these feel like woods we have no business going into. Nature is framed as something ominous, ungodly, whose sweet gifts (i.e., apples) are used to lure. Paired with Mark Korvern’s score, which plays magnificently over our first images of the eponymous creature as she overtakes the visage of the moon, there’s a lot to admire in this expertly mounted first feature.

By its chilling final frames, the paranoid delusions of the Puritanical mind have been salvaged for one properly unnerving nightmare. Painstakingly based on actual journals and records from the period, Eggers’ film is a chilling moral lesson concerning the power of community (power in numbers) over religion. The script captures perfectly the dominating, obsessive fear of religion, present in almost every exchange of dialogue—an institution so repressively draconian necessitates an equally powerful opposition. Without a doubt, there are things to fear in these realms of sacred and profane, but at the end of the day, one can never really anticipate what will come crawling out of the bowels of the primeval forest.

Reviewed on January 28 at the 2015 Sundance Film Festival – US Dramatic Competition. 92 Mins.

★★★½/☆☆☆☆☆