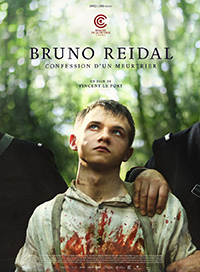

The Killer Inside Me: Le Port Mines the Makings of a Murderer in Detached True Crime Sketch

Director Vincent Le Port revisits a chilling murder in 1905 Cantal, France wherein a 17-year-old seminarian decapitated a 13-year-old boy in Bruno Reidal, Confession of a Murderer. Less salacious and more clinically detached than its title otherwise suggests, Le Port weaves an early attempt at criminal psychology in this (mostly) serene recount of a shocking murder when the teenage killer is goaded into writing his memoirs at the behest of a panel of three physicians desiring to know why such a senseless and violent act was committed.

Director Vincent Le Port revisits a chilling murder in 1905 Cantal, France wherein a 17-year-old seminarian decapitated a 13-year-old boy in Bruno Reidal, Confession of a Murderer. Less salacious and more clinically detached than its title otherwise suggests, Le Port weaves an early attempt at criminal psychology in this (mostly) serene recount of a shocking murder when the teenage killer is goaded into writing his memoirs at the behest of a panel of three physicians desiring to know why such a senseless and violent act was committed.

By today’s standards, we’ve encountered countless killers reduced to ‘monsters’ in the media who have plagued populations all over the globe. And yet, despite a myriad of instances suggesting the same conclusion, we’ve become socially desensitized to a dangerous collusion between the right mix of hardwired nature encountered by the required dose of toxic nurture allowing for these savage stars to align. Of course, neither Le Port nor civilization at large offers concrete insight or foolproof solutions, and yet this morose exercise suggests we continue to ignore the obvious in pursuit of alternative self-interests.

On one otherwise ordinary day in 1905, 17-year-old seminarian Bruno Reidal (Dimitri Dore) decapitates a younger boy in the forest outside his village and turns himself in. To understand why, a panel of doctors led by Lacassagne (Jean-Luc Vincent) questions Reidal and commands him to write his memoirs. As the panel unfolds, Reidal’s memoirs provide a flashback mechanism for his troubled childhood with abusive parents and emotionally distant siblings. Following an episode of sexual abuse, Reidal’s dark longings would comingle with fantasies of murder and the continual wish to maim or kill his fellow male classmates. A thwarted fixation on a handsome student leads him to pick a random victim to fulfill his obsessive, murderous needs.

While Fincher’s series “Mindhunter” revisited the historical advancements of criminal psychologists finally discovering the necessity of studying serial killers and their psychological patterns, Bruno Reidal is a reminder of how such research has always been an interest of our own grisly fascination. By 1905, such aberrant violence was, of course, nothing new. Jack the Ripper terrorized London in the 1880s, and the first recorded serial killer in the U.S. was H.H. Holmes in 1880s Chicago. Urban alienation and the Industrial Revolution are often key indicators in these sagas, and while Reidal did not commit a killing spree, he serves as a prototype for Jeffrey Dahmer a la the classic 1824 Scottish text by James Hogg, The Private Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner.

Le Port opens directly upon the brutal murder, although the actual decapitation occurs offscreen, to be revisited later at the end of Reidal’s memoirs. The panel of doctors led by Lacassagne are coldly inquisitive but prod their subject directly in ways cinema has not often been allowed to depict, especially as regards to serial killers with latent homosexual tendencies (Fritz Lang’s 1931 cornerstone, M. even changed the actual sexual orientation of the real-life Peter Kurten).

Newcomer Dimitri Dore (plays opposite Isabelle Huppert in Joan Verra) is a melancholic glitch of a human, diminished in life both before and after his heinous act. With chilling conciseness, he relays his journey of emotional neglect and penchant for sadism born from watching animals being slaughtered, coinciding with his rape by an errant shepherd. The commingling of bloodlust and sexuality is a striking portrait of how the treatment of children is indicative of these eventual shocking actions, and Reidal’s memoir paints a haunting roadmap suggesting ways his narrative could be stymied if only circumstances would detect these behaviors, or their environmental contributions, preemptively. The most chilling sequence Le Port delivers is not the actual decapitation itself, but the sole moment where the downcast Dore comes to life with a delirious smile.

Had Bruno Dumont cared to forgo Joan of Arc to focus on Bruno Reidal, one can only imagine the wonders of his (potential) anachronistic soundtrack. All the talk of masturbation begs for the insidious accompaniment of Mindless Self Indulgence, while the formidable use of Deep Purple’s “Child in Time” (used strikingly in another Cannes premiere in the same sidebar, Softie). But Le Port chooses to keep this a bit sobering, and even if he still recalls Dumont (Camille Claudel, 1915, also starring Dumont alum Jean-Luc Vincent), DP Michael Capron’s (Fort Buchanan, 2014) beautiful cinematography channels the period enigma of something like Daniel Vigne’s The Return of Martin Guerre (1982). Upsetting and disturbing, Bruno Reidal is challenging arthouse horror, and suggests Vincent Le Port as a budding provocateur.

Reviewed on June 12th at the 2021 Cannes Film Festival – Critics’ Week – Special Screening. 101 Mins.

★★★½/☆☆☆☆☆