You Can’t Handle the Fugue: Schroeter Burns Bright with Infamous Bachmann Adaptation

What is it about Werner Schroeter’s Malina so seemingly repellant it resulted in almost immediate obscurity, as dismissed in cinematic form in 1991 as Ingeborg Bachmann’s 1971 novel remains a celebrated, nearly unparalleled cornerstone of the female psyche? Initially, it premiered in competition at the Cannes Film Festival, where the Roman Polanski led jury awarded the Coen Bros. Barton Fink with the Palme d’Or and Irene Jacob took home the Best Actress prize for her work in Krzysztof Kieslowski’s The Double Life of Veronique, both films which are strangely similar in content and form, the former a Kafkaesque nightmare about Hollywood filmmaking and the latter a twin refraction of two profoundly connected women played by the same person, mirror images of opposing desires and needs.

What is it about Werner Schroeter’s Malina so seemingly repellant it resulted in almost immediate obscurity, as dismissed in cinematic form in 1991 as Ingeborg Bachmann’s 1971 novel remains a celebrated, nearly unparalleled cornerstone of the female psyche? Initially, it premiered in competition at the Cannes Film Festival, where the Roman Polanski led jury awarded the Coen Bros. Barton Fink with the Palme d’Or and Irene Jacob took home the Best Actress prize for her work in Krzysztof Kieslowski’s The Double Life of Veronique, both films which are strangely similar in content and form, the former a Kafkaesque nightmare about Hollywood filmmaking and the latter a twin refraction of two profoundly connected women played by the same person, mirror images of opposing desires and needs.

So, what is it about Schroeter’s offering so off-putting? After all, it features the sort of galvanizing, no-holds-barred performance from Isabelle Huppert she’d later be systematically praised for in a series of comparable characterizations of complicated, arguably ‘difficult’ women struggling valiantly to straddle the need of defining their own agency while desiring the recognition for attributes prized by the heteropatriarchy—in short, a non-linear rumination on archaic cultural standards designed only to stifle her. The exact, most complex nexus of these energies, in the realm of Huppert at least, is crystallized perfectly through this Bachmann adaptation, while the film, like the novel, remains both ahead of its time but denied recognition in a visual format more queasy about cerebral ambiguity than permitted in literature. The reaction to the film at its 1991 Cannes premiere was named Huppert’s worst Cannes moment in a 2017 interview on the Croisette with The Hollywood Reporter and its subsequent unavailability (a R2 Blu-ray from Concorde Video in 2011 remains it’s only tangible home entertainment release), like most of Schroeter’s work despite being a key member of the New German Wave, remains formidably obscured prior to Mubi’s release of the title’s restoration in 2020.

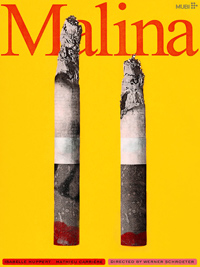

A woman (Huppert), whose name is never revealed, is a struggling writer and professor. She lives with her long-term partner Malina (Mathieu Carriere), a historian with whom life has become somewhat rote. She finds herself enamored with a younger man, a Hungarian named Ivan (Can Togay). Her intensity begins to alienate Ivan, who can never seem to respond passionately enough, and it soon dawns on her she will never be able to find someone, a man, who will be everything she needs. Addicted to pills and cigarettes, her external environment begins to reflect the increasingly hellacious torture of her internal emotional discord.

Perhaps what’s most uncomfortable about Malina as this film version is the juxtaposed queerness—there’s just something undeniably off in these unions between queer auteurs who are attracted to portraying characterizations of neurotic women without simultaneously sexualizing them. Roman Polanski created a cornerstone of this genre with 1965’s Repulsion, an examination of a woman come undone, but also a film where we are as transfixed by the chilly beauty of Deneuve. Altman’s Images (1972) or Cassavetes’ A Woman Under the Influence (1974) tread similar terrain, but Schroeter (whose 1973 Willow Springs provided the template for Altman’s 1977 3 Women) dives headlong into a turbulent, sometimes psychotic rendering of a woman split between jarring needs and desires, with confrontations stemming from her father and an equally unfulfilling intimate connection with two men, arguably both supportive but neither able to quite fulfill her.

And perhaps this unabashed discomfort, with Huppert’s anguish and a refusal by Schroeter to confirm or conform to anything beyond a raw ganglion of emotional misanthropy, is what makes his version of Malina seem more a visual castigation than the more immersive experience of reading Bachmann’s stream of consciousness prose (which is considered a response to Max Frisch’s 1964 novel Let’s Assume My Name is Gantenbein, with whom she was romantically involved with, living together from 1958 to 1963). And yet, this isn’t (because it simply cannot be) a straightforward adaptation, and Schroeter seems to be collapsing the author herself into one faction of this woman’s identity, which really aligns the film as a wholly original experience, not unlike what David Cronenberg wielded with his 1991 adaptation of William S. Burroughs’ 1959 novel Naked Lunch—the author becomes the framework for an incomprehensible novel which reads like a long winded howl from a self-medicated brain. Huppert’s rendition isn’t unlike the Judy Davis persona of Cronenberg’s film and her memorable ‘Kafka high,’ but rather than Kafka, this is a jarring struggle for a woman’s self-agency somewhere between the spectrum of Sylvia Plath and Anna Kavan (“I said we’ll phone each other now and then!” she screams at one point, one of many primal rages which are so overwrought one can’t help but be amused at some of her preoccupations).

The masculine constellations in the life of the unnamed protagonist mutate in their symbolism, memories and roles. Bachmann’s novel increasingly begins to focus in its second segment on her father, a man Schroeter also represents as an anguished remnant of Austria’s Nazi history. The titular Malina, who may or may not be merely a figment of her imagination, is potentially a refracted defense mechanism from a traumatic childhood who becomes more of an intangible witness to her self-destruction. Their relationship feels neutered, sexless, sometimes prickly and violent. Schroeter invokes a continual fairy tale element, such as a trip to the movies with Ivan’s children where she disappears into her own mind, which begins to posit Malina as her savior figure, a prince charming gone to seed.

Constant interruptions of others in the throes of lovemaking seems to cement her as a woman precariously positioned on the outside of her own life’s experiences, and in many ways Malina predates a variety of films and performances which Huppert would becomes better known for, defiant intellectuals in self-destructive breakdowns, like The Piano Teacher (2001). Vomiting inside her purse while heavily intoxicated in a restaurant recalls the same film, or even Haneke’s Time of the Wolf (2003). Ridiculously large Maine Coons likewise tie into later feline juxtapositions in films like Things to Come or Elle (both 2016).

And one cannot overlook the presence of Nobel Prize winning author Elfriede Jelinek, adapting Bachmann. Like with The Piano Teacher, this is a melding of prominent female influencers from literature and cinema, and with Schroeter stirring the pot, it’s inevitable to reinterpret the film in several ways. Huppert, like with Haneke, is a foreigner to the Vienna set source material, which also causes some distance. Jelinek, well known for her highly critical narratives of her native Austria almost seems to be writing the Bachmann/Huppert figure as representative of the country itself, haunted by the sins of the father and struggling to find footing between the tried and true stability of a traditional relationship, one which might even afford her a semblance of equality, and that of an object of desire with a younger man whose affections for her eventually seem untenable. “No one person can satisfy every need,” is a refrain in both film and novel, but as Huppert vocalizes in her various asides teaching Wittgenstein, “history teaches lessons but has no students,” and so, at least as Schroeter paints her, when her mirror images confront Malina and she says “If you don’t hold me now, it’s murder,” she becomes the essence she’d been so valiantly trying to escape from, reduced to a vessel of raw human need. But whether or not Malina is a version of herself or merely a conduit, the idea of another human we all are conditioned to pour ourselves into as a way to secure not only a witness to experience but grasp at tangible meaning, it’s a distressing portrait of a woman in the process of a slow-burn self-immolation. And perhaps at last, three decades after its release, we can rediscover the brilliance of Bachmann, whose troubling designs have created descendants like Charlie Kaufman.

Schroeter dedicated his film to Jean Eustache, who passed away a decade earlier, but whose 1973 masterpiece The Mother and the Whore is the masculine inverse of Malina, and perhaps a key to what the two men are supposed to represent here, at least as far as dichotomized givens are concerned—the savior and the lover, both who seem to have a date of unavoidable expiration.

★★★★½/☆☆☆☆☆