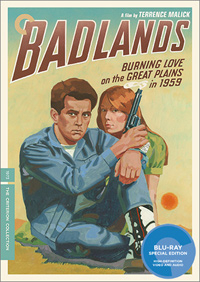

1973’s Badlands marked the first feature film from writer/director Terrence Malick and it squarely put him on the path to his current cinematic sainthood. Over a forty year career and a scant six feature films — three more are on the way — Malick has established a well deserved mystique as the closest thing America has produced to a true European style auteur. Frankly, no one else is even close. Ironically, one could make a case that the artistic influence of this Oklahoma farm boy has its deepest resonance far beyond America’s shores. Directors such as Turkey’s Nuri Bilge Ceylon and Mexico’s Carlos Reygadas reverently evoke Malick’s pantheistic zen, while Thailand’s Apitchapong Weerasathakul’s slow, stately dolly shots of weeds and bushes make him perhaps Malick’s most direct artistic descendent.

1973’s Badlands marked the first feature film from writer/director Terrence Malick and it squarely put him on the path to his current cinematic sainthood. Over a forty year career and a scant six feature films — three more are on the way — Malick has established a well deserved mystique as the closest thing America has produced to a true European style auteur. Frankly, no one else is even close. Ironically, one could make a case that the artistic influence of this Oklahoma farm boy has its deepest resonance far beyond America’s shores. Directors such as Turkey’s Nuri Bilge Ceylon and Mexico’s Carlos Reygadas reverently evoke Malick’s pantheistic zen, while Thailand’s Apitchapong Weerasathakul’s slow, stately dolly shots of weeds and bushes make him perhaps Malick’s most direct artistic descendent.

Back in the U.S., the cult of Malick has grown to such glowing stature that A List stars desperately queue up to work with him. In the case of The Tree of Life, Brad Pitt essentially paid for the privilege by partnering with Malick’s company and ponying up his own funds for the production. To the current state of Malick’s career, Ira Gershwin’s immortal phrase “nice work if you can get it” certainly applies.

It’s also ironic that Hollywood’s brightest and best are consumed with Malick-mania, considering that few of his cinematic excursions could rightfully be considered actor’s showcases. In fact, no Malick directed performance has ever been nominated for an Oscar. Much like Kubrick, Malick works in scales that make human beings seem weak and superfluous; mere squawky annoyances while the gods go about their divine labors. Whether the subject is a company of WWII grunts or a laconic Texas wheat farmer, Malick’s characters are ultimately flyspecks scattered and lost in a limitless horizon.

Badlands often attempts a similar escape to astral plains, but Malick’s chops were still in their infancy and unable to best an irresistible force named Martin Sheen. Based loosely, to put it mildly, on a famous 1958 Nebraska killing spree, Badlands details the life and times of an aimless punk named Kit (Martin Sheen) and his burgeoning romance with Holly (Sissy Spacek), a shy, sheltered high school student and aspiring majorette. When Kit, whose gnarled life has thus far been a textbook case of passive-aggressiveness, finds himself at odds with Holly’s disapproving father (Warren Oates), their tensions eventually lead to sudden and shocking violence. Soon, Kit and Holly find themselves on the lam with the authorities in hot pursuit and more violence their only source of temporary reprieve. Over the next few weeks, the couple live a primitive, shadowy existence while Kit’s worsening mental state pushes them to a bloody and disastrous brink.

On paper a garden variety true crime film, Badlands is replete with the signature Malick stylistics that would eventually define his oeuvre. The strains of Satie and Orff that adorn its track are the first hint that Badlands will seek to break the genre’s hard boiled constraints. The film introduces its characters through small, seemingly insignificant scenes that make its eventual violent trajectory all the more stunning. Set in a leafy enclave of tidy working class homes — a neighborhood virtually identical to Brad Pitt’s in The Tree of Life — Malick embraces the sunny imagery of Americana while creating a surreal poetry that exposes its hollows and disappointments. His rough-hewn tradesmen may emit a steely practical focus and Aw Shucks veneers, but swirling around them are unseen and unbridled spirits, barely tamped down and capable of enormous destruction. Spacek’s wispy Texas twang provides the film’s narration, but in typical Malick fashion she never obtains omniscient status. Few filmmakers have ever been able to shift points-of-view as nimbly as Terrence Malick. His willingness to break narrative conventions create a mystical distance between viewer and subject. While most directors struggle mightily to make their films more immersive and realistic, Malick’s objective is to transport his audience to lofty Olympian peaks.

Martin Sheen’s turn as Kit is an extraordinary bit of work and likely ranks as the single best performance in Malick’s impressive filmography. Built on a thousand unnerving details, Sheen’s embodiment is a primer in the special effects of off beat line reading and eccentric timing. In the aftermath of his assorted atrocious acts, the remorseless Kit desires nothing more than a swift return to life’s banal rhythms; spouting trivial chitchat while his victims lay dying at his feet. After returning from hiding a murdered body, Kit calmly announces that he’s found an old toaster amid a pile of debris. In a burst of inspiration, he decides to wipe his fingerprints from a crime scene door knob after he’s spent the better part of a day touching everything else in the house. In many ways the film’s epilogue is its best scene, and here Sheen’s sudden charm bewitches his opponents, rendering them befuddled by his charisma.

Despite his boyish looks, Sheen was already a veteran actor when he stepped onto the set of Badlands. He cut his teeth in the great television experiments of the Kennedy years, when network executives seemed emboldened by the young President’s quest for New Frontiers. Cops and cowboys were losing ground to slice-of-life shows and dramatic anthologies that dealt with the deepening cracks in the American Dream. Sheen was a staple in all of them, from the innovative series Route 66 to the topical social work drama East Side/West Side. Honing his craft on the small screen taught Sheen the subtleties of dynamics and how to dominate without being greedy. Throughout his long career, whether playing a small time hood, a tortured army captain in an insane landscape or a beleaguered Commander-in-Chief, Sheen fills the space with a presence that seems perfectly measured. In later Malick films, the actors — despite their fame — are little more than cogs in the director’s grand schemes, but Badlands simply wouldn’t have worked without Martin Sheen.

Disc Review

Criterion sourced the 1.85:1 transfer from the original 35mm camera negative and the results are pristinely “filmy” while retaining the crisp openness that distinguishes OCN authorship. Grain is virtually nonexistent, with excellent shadow detail. The photography itself is remarkably consistent, especially since at one time or another the project employed three different DPs. Those expecting a Life of Pi style display of hi-def wonderment may be disappointed, but the look of Badlands is a superb example of early 1970s visual provenance.

The audio is in mono and is equally lose-less, having been mastered from the original 35mm mags. Eq’ed essentially flat, the mix delivers the film’s dissonant line mutterings with a refreshing, easygoing clarity.

Making Badlands, a new documentary featuring actors Martin Sheen and Sissy Spacek and art director Jack Fisk

This 42 minute presentation is a fairly typical behind-the-scenes doc, but its occasional insights into the reclusive Terrence Malick give it an interesting hum. Sheen discusses the story’s real life background and his impressions of the young Malick, including a few funny stories about the director’s gentle and unconventional persona. Spacek recounts her acting background and the surprising role her skill in baton twirling played in shaping the narrative. Fisk addresses the challenges of designing sets for such an intuitive and spontaneous filmmaker. Throughout each interview, the subjects’ deep respect for Terrence Malick is palpable and gives the supplement an unusual personal depth.

New interviews with associate editor Billy Weber and executive producer Edward Pressman

Weber goes into great detail on the editorial nuances of Badlands and supplies several scenes that illustrate Malick’s techniques. He also discusses Malick’s admiration for Truffaut’s The Wild Child and its influence on the final script.

Pressman talks about meeting Malick at Harvard and the various financial gymnastics he had to perform with his family’s fortune to get Badlands funded. He reveals how several of the Hollywood veteran crew members doubted the fledgling director’s competence, including the script supervisor who resigned over Malick’s lack of concern over continuity. The two interviews are fascinating and run a combined 34 minutes.

Charles Starkweather, a 1993 episode of the television program American Justice, about the real-life story on which the film was loosely based

Using some rather gristly news footage, this program offers a brisk recap of the events that inspired Badlands. However, the bulk of the show deals with the lengthy investigation into the degree of guilt of Starkweather’s accomplice Carol Fugate. Beyond background in the case, the supplement’s chief takeaway is the tremendous liberties Malick took in his version of the story, which ultimately bore little resemblance his source. 20 minutes.

Trailer

The film’s original U.S. trailer is included, focusing mainly on Badland’s sparse action sequences.

A booklet featuring an essay by filmmaker Michael Almereyda

Using a selection of Flannery O’Connor quotes as a frame, Almereyda’s workmanlike analysis will be worthy reading for any Malick fan. The 20 page booklet also contains an array of film stills, production credits and notes on the transfer.

Final Thoughts

Despite its gruesome elements, Badlands — much like its creator — manages to retain a vital element of innocence. Underneath his revolutionary aesthetics and recondite spiritual musings, Terrence Malick seems to still believe in mankind’s worthiness to inhabit the glowing natural world his films depict. The darkly reticent characters of Badlands may seriously challenge that theory, but the film is a significant first step in the evolution of America’s most interesting director. Produced at a time of national disillusionment, Badlands attempts to capture the stark contrast between America’s heroic mythology and her louche reality. By employing an early version of his now famous poetic lingua franca, Terrence Malick achieved his goal, while serving notice of cinematic marvels to come.