Indie Film News

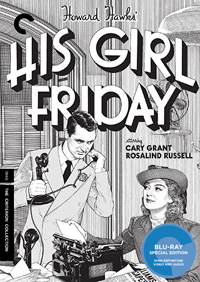

Criterion Collection: His Girl Friday | Blu-ray Review

When it comes to Howard Hawks, it’s easy to forget the prolific American auteur set the gold standard for a number of film genres, including his iconic Westerns (Red River, 1948; Rio Bravo, 1959) and labyrinthine spasm of film noir (The Big Sleep, 1946). But he remains unparalleled in the art of the screwball comedy, even those titles which initially flopped at the box office (including the 1938 career best Bringing Up Baby), which are continually referenced today. From 1934’s Twentieth Century through his showy collaborations with 1950s icon Marilyn Monroe, including the juggernaut Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (1953), Hawks is perhaps the most influential yet least heralded auteur from Hollywood’s Golden Age, awarded an Honorary Oscar in 1975 just two years before his death, despite having delivered some of the most notable American cinema during his prolific decades ranging from the 1930s to the end of the 1950s. From his body of work, one of his most notable achievements is the repeated presentation of intelligent, ‘tough-talking’ women characters who stood on equal ground with their male leads, which was eventually coined into a definable term as the “Hawksian Woman.” Perhaps none of them outrank the glorious journalist portrayed by pitch-perfect Rosalind Russell (in his 1940 remake of Lewis Milestone’s 1931 title The Front Page) as the self-assured, highly talented Hildy of the farcical His Girl Friday.

When it comes to Howard Hawks, it’s easy to forget the prolific American auteur set the gold standard for a number of film genres, including his iconic Westerns (Red River, 1948; Rio Bravo, 1959) and labyrinthine spasm of film noir (The Big Sleep, 1946). But he remains unparalleled in the art of the screwball comedy, even those titles which initially flopped at the box office (including the 1938 career best Bringing Up Baby), which are continually referenced today. From 1934’s Twentieth Century through his showy collaborations with 1950s icon Marilyn Monroe, including the juggernaut Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (1953), Hawks is perhaps the most influential yet least heralded auteur from Hollywood’s Golden Age, awarded an Honorary Oscar in 1975 just two years before his death, despite having delivered some of the most notable American cinema during his prolific decades ranging from the 1930s to the end of the 1950s. From his body of work, one of his most notable achievements is the repeated presentation of intelligent, ‘tough-talking’ women characters who stood on equal ground with their male leads, which was eventually coined into a definable term as the “Hawksian Woman.” Perhaps none of them outrank the glorious journalist portrayed by pitch-perfect Rosalind Russell (in his 1940 remake of Lewis Milestone’s 1931 title The Front Page) as the self-assured, highly talented Hildy of the farcical His Girl Friday.

Hildy Johnson (Russell), a renowned reporter, returns from a four month absence at work to announce her permanent hiatus. Having used the period of time to obtain a divorce from her husband and boss Walter Burns (Cary Grant), managing editor of the Chicago paper The Morning Post, Hildy has decided to be a housewife with new beau Bruce Baldwin (Ralph Bellamy), an insurance salesman with whom she is catching a 4 o’clock train so they may be married the following day in Albany. In an attempt to rejuvenate her passion for her chosen profession, Walter pulls a number of shenanigans to convince Hildy to cover one last major story, the impending hanging of a convicted simpleton, Earl Williams (John Qualen), accused of killing a black police officer and due to be executed the next morning. Hildy, despite knowing better, takes the bait.

The less critically and historically celebrated Lewis Milestone was a two time Oscar winning director by 1931 (having taken statues for All Quiet on the Western Front and Two Arabian Knights), and would even score a nod for The Front Page. To watch the titles in succession, however, is only evidence of the energy and cinematic magic Hawks was so easily able to inject into material already deemed entertaining, namely by switching the gender of Hildy Johnson to a woman, keeping the same nickname (Hildebrand became Hildegard) and many of the same witty rejoinders from the original play by Ben Hecht and Charles MacArthur. To be fair, Milestone, who like Hawks also straddled the significant divide between the silent era and the stiffness of the early talkies, was a more than competent director, giving Joan Crawford one of her best serious roles (and least liked) with the 1932 W. Somerset Maugham adaptation Rain, while also responsible for the early noir standard The Strange Love of Martha Ivers, which featured a dark love triangle between Barbara Stanwyck, Van Heflin, and Kirk Douglas—and yet, he had not the masterful comedic ear as Hawks did, who better captured the essence of his various screenwriters (here Charles Lederer and Morrie Ryskind take credit for giving the adaptation a face-life) and actors, given free rein to improvise.

His Girl Friday (the title meant as a play on Robinson Crusoe’s sidekick Friday, a term used to convey loyalty and servitude) was Hawks’ third collaboration in a row with Cary Grant, following Bringing Up Baby (1938) and Only Angels Have Wings (1939), afterwards leaving the star behind for repeated pairings with Gary Cooper, and then, perhaps most famously, his Humphrey Bogart/Lauren Bacall titles (Grant would later appear in 1952’s Monkey Business). And to be honest, Grant, though entertaining, is eclipsed by Russell, who swallows everyone else in her wake, as well. Though she wasn’t the first choice to play Hildy Johnson (rumors abound on Hollywood politics of the period, with names like Jean Arthur, Joan Crawford, Katherine Hepburn, Ginger Rogers, etc. all apparently having been offered the role first), Russell clearly made it her own, in what’s often cited as the first major film production to showcase actors talking over one another’s dialogue.

The sassy, fast-talking Russell (who stole all her scenes a year prior in Cukor’s The Women) emerges as one of the most vibrant female characterizations in 1940s American Studio cinema (and one wonders how she could have wiped the floor in 1937’s vintage comedy The Awful Truth alongside Grant rather than Irene Dunne), her off-the-cuff ad-libbing perfectly in synch (if not better) with what remains of Hecht and MacArthur’s original bits of dialogue. The revamped title and several allusions within the dialogue pertaining to racial others, including a black woman giving birth as part of an elaborate newsman’s joke at the expense of the doltish sheriff, contain a whiff of discomfort, but Hawks tends to lessen the unseemly elements (like making the character Molly Malloy less obviously a sex-worker, while John Qualen’s escaped convict is not shown murdering the pretentious psychoanalyst at gunpoint as his character does in The Front Page). At the same time, the political agenda concerning justice surrounding the murder of a black police officer seems simultaneously progressive, despite the usual lack of varied skin tone amongst on-screen cast and characters from this period.

Technically speaking, there’s not much different than Milestone’s previous film, with nearly all the film taking place in the interior of the pressroom at the courthouse. The major exception is a smoke-filled lunchtime sequence wherein Grant gets to prove to the audience how ill-suited Ralph Bellamy’s hapless and dull fiancé is for Hildy. But the flurry of energy zinging in and out of the press room keeps His Girl Friday in a thrall of constant movement, unlike the rather lethargic sequences of Milestone’s version, which is a drably filmed stage play. Here, DP Joseph Walker (who was responsible for several of Frank Capra’s most noted works, plus scoring his second of four Oscar nods for Hawks’ Only Angels Have Wings) keeps the framing snappy, enhanced by editor Gene Havlick (who was often paired on those Capra films with Walker), the focal point often being Russell’s wide ranging facial expressions, dressed as she is like an executive styled bird.

Disc Review:

His Girl Friday was unfortunately one of those titles which fell into the public domain at one point, so many generations of audiences have experienced it in sub-par prints or on barely serviceable DVD transfers. Those days are all over now thanks to the Criterion Collection, presenting the title as a brand new 4K high-definition digital restoration with uncompressed monaural soundtrack (which is important considering the zesty dialogue which could easily be lost in the din of various elaborate sequences). Picture and sound quality are outstanding (for anyone who ever watched a poor print of this on the past, which includes various theatrical screenings, where the title is often included in various vintage themed screwball comedy retros, this is the ticket).

Hawks on Hawks:

This ten minute segment, heralded as part of a new shorts program, is composed of excerpts from a 1972 audio conversation between Hawks and Peter Bogdanovich, as well as a 1973 interview of Hawks with Richard Shickel, wherein the director reminisces about casting the film and the changes to the original source material.

Lighting Up with Hildy Johnson:

Film scholar David Bordwell, co-author of Film Art: An Introduction, conducts this visual analysis of Hawks’ His Girl Friday, which he believes to be the apotheosis of classical Hollywood storytelling.

On Assignment – His Girl Friday:

This nine minute segment features author David Thomson and Molly Haskell expressing his thoughts on how the film is one of the greatest American films ever made.

Howard Hawks – Reporter’s Notebook:

This brief three minute clip swiftly narrates the career and rise of Howard Hawks.

Funny Pages:

This three minute bonus is another narrated mash-up of clips as a backdrop to showcase the title’s history as a play by Ben Hecht and Charles MacArthur.

Rosalind Russell – The Inside Scoop:

And Rosalind Russell gets her own narrated glancing over of her prolific career.

Lux Radio Theater:

Criterion includes this Lux Radio Theater adaptation of His Girl Friday, which aired September 30, 1940 with Claudette Colbert as Hildy Johnson and Fred MacMurray as Walter Burns.

The Front Page:

Criterion includes a recently restored transfer of Lewis Milestone’s The Front Page on a separate disc in the packaging. Be forewarned, watching this so shortly after the beauty of His Girl Friday may make the experience seem tiring.

Final Thoughts:

Though it may not be as quotable as something like All About Eve (1950), Howard Hawks’ incredibly funny His Girl Friday showcases the supreme comic talents and timing of the furiously funny Rosalind Russell.

Film Review: ★★★★/☆☆☆☆☆

Disc Review: ★★★★/☆☆☆☆☆