The Criterion Collection: Ugetsu | Blu-ray Review

A cornerstone of Japanese cinema, Kenji Mizoguchi’s 1953 masterpiece Ugetsu at last receives an updated transfer from the Criterion collection. In the middle of a trio of Venice Film Festival award winners (1951’s The Life of Oharu; 1954’s Sansho the Bailiff) which solidified Mizoguchi’s international reputation and influential shadow on his country’s cinema, it is deservedly his most revered achievement both in tone and form.

A cornerstone of Japanese cinema, Kenji Mizoguchi’s 1953 masterpiece Ugetsu at last receives an updated transfer from the Criterion collection. In the middle of a trio of Venice Film Festival award winners (1951’s The Life of Oharu; 1954’s Sansho the Bailiff) which solidified Mizoguchi’s international reputation and influential shadow on his country’s cinema, it is deservedly his most revered achievement both in tone and form.

In his essay on the film, critic Philip Lopate succinctly explains “Mizoguchi’s formalism and humanism are part of a single unified expression.” An expressive ghost story combining short stories by Akinari Ueda and Guy de Maupassant, Mizoguchi continues his exploration of humans trapped in undesirable social circumstances by juxtaposing two families whose husbands sacrifice familial stability at the expense of their wives during wartime.

War is on its way to the farming village of Nakanoga in 16th century Omi Province, Japan. Genjuro (Masayuki Mori) is a potter who sees the current conflict as a means to maximize profits by selling his wares to both sides, which necessitates his traveling outside their village. His wife Miyagi (Kinuyo Tanaka) would rather Genjuro stay home with their son and focus on enjoying their day-to-day existence. Genjuro is accompanied by his brother Tobei (Eitaro Ozawa), a farmer who desires to be a samurai but lacks the money to buy himself the proper armor which would give him a fighting chance of becoming one.

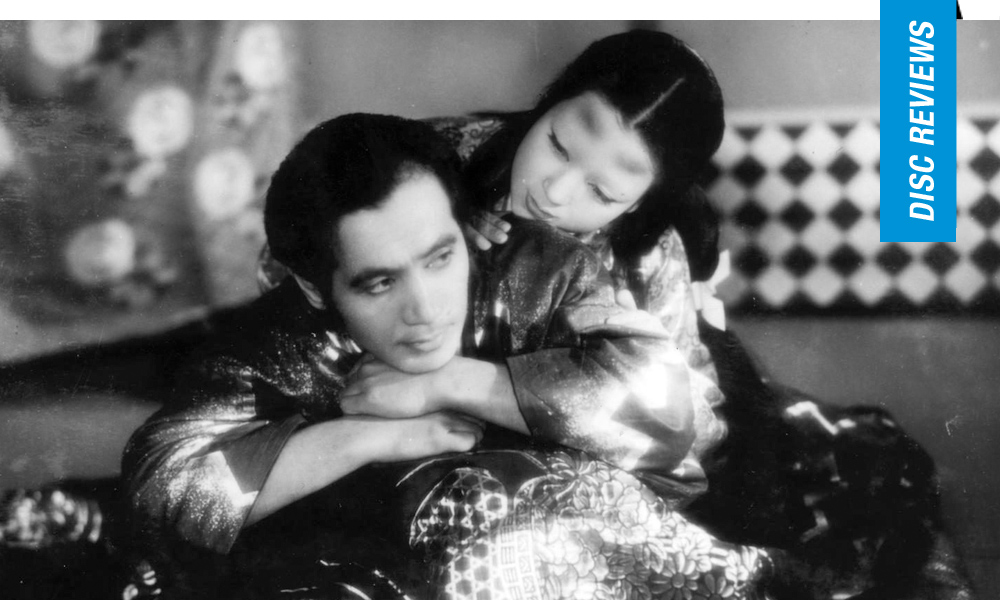

Tobei’s wife Ohama (Mitsuko Mito) is also unenthused about her husband’s lofty ambitions during such a tenuous period. When General Shibata’s army finally reaches their village, the two couples flee by boat, but upon running into another vessel where a mysterious man warns them of pirates and urges they turn back, the brothers attempt leave their wives on the shore, but Ohama refuses. Circumstances eventually force all of them to separate, with Tobei realizing his desires via a devious stroke of luck, while Genjuro becomes enthralled with a mysterious noblewoman, Lady Wakasa (Machiko Kyo), who seduces him into a marriage union at her castle.

Ugetsu opens with Mizoguchi’s signature flourish, his “flowing scroll,” as the camera pans across a cluster of dwellings, the sounds of conflict off-screen signaling the encroaching danger soon to sweep over it. Preferring one take long shots, Mizoguchi’s actors are almost never seen in close-up and certainly never glamorized, including famed Machiko Kyo as the ghostly Lady Wakasa, whose face is painted like a white Noh mask.

Although DP Kazuo Miyagawa isn’t nearly as estranged from the film’s subjects as the kabuki chronicles of the tragic The Story of the Last Chrysanthemum, the film’s rhythm is wrapped up in its hypnotic mise-en-scene, which Mizoguchi uses to lull us into familiar territory and then deftly upends us into magical realism.

The first, and perhaps most magnificent sequences is the famed boating scene, where the two couples drift through a fog after barely escaping Shibata’s men in their devastated village. Encountering a slumped over man in drifting boat, they receive an ominous warning and we wonder if he’s actually of the spirit realm, appearing more as a warning to the women as they blindly follow their husband’s despite questionable ambitions. The next is a collapsing sequence where Genjuro and Lady Wakasa frolic playfully in a swimming pool which segues to a picnic, as he is further seduced not along by her appeal to his pride by complimenting his craft. “I did not know pleasures such as these existed,” he cries in a swoon.

Earlier, Mizoguchi showed us the cruelty of what happened to Genjuro’s wife and child, not to mention a rape sequence of Ohama, the men descending on her like a pack of wolves set on devouring her. It’s no surprise, then, when Lady Wakasa and her defunct nursemaid eventually are dismayed with Genjuro, a man blind to his privilege and the havoc he wreaks when he withdraws his ‘support.’

Mizoguchi’s films often depicted the tragic plight of women on society’s periphery (his last film was a superb drama about a brothel of prostitutes in 1961’s Street of Shame), and while neither of the three main female characters in Ugetsu are allotted the same narrative leeway as his earlier The Life of Oharu (in which Kinuyo Tanaka, the Japanese Bette Davis, memorably stars as the eponymous lead), it is a film which could be easily construed as a women’s picture. Forced to become a geisha after her sexual assault, Ohama cries upon her reunion with Tobei, “success always comes with a price in suffering.” In Ugetsu, it’s the women and children who ultimately suffer, even those not raped or murdered, those unnamed women we see crying out early on as their men are forced into military service, fearing starvation and degradation.

If Ohama and Miyagi are familiar composites for Mizoguchi, Lady Wakasa (Machiko Kyo was also in Rashomon and Kinugasa’s sumptuous color film Gate of Hell) and her nurse are another story, from a nether region beyond the social realism he most often depicted. Their rage, dismay, and underlying manipulation of men to have certain needs met recalls Kaneto Shindo’s genre infused Kuroneko, wherein two women who are raped and murdered by soldiers come back as spirits who seduce and kill men passing by their lair.

Ugetsu is more of a poetic reflection of women as the sacrificial casualties of war, although not exactly damning the ambitious desires of their husbands, men who don’t wish to abandon their families, but in their foolhardy way are unable to account for the consequences their actions wreak.

Disc Review:

Criterion presents Ugetsu as a new 4K digital restoration with uncompressed monaural soundtrack in its original aspect ratio 1.37:1. Martin Scorsese and Masahiro Miyajima supervised the restoration, which results in this stellar new package. Kazuo Miyagawa’s (this was three years after his work on Kurosawa’s Rashomon) long, sweeping takes are sumptuous in this new format, perhaps the title most deserving of upgrade from Criterion’s back catalogue.

Interviews:

Criterion includes several interviews, such as a fourteen minute segment from 2005 with Masahiro Shinoda (director of Pale Flower and Double Suicide), a twenty minute bit with first assistant director Tokuzo Tanaka (also from 2005), and a ten minute 1992 interview (recorded for Criterion’s laserdisc release) with DP Kazuo Miyagawa.

Kenji Mizoguchi – The Life of a Film Director:

Director Kaneto Shindo made this comprehensive two-and-a-half hour 1975 documentary on Mizoguchi’s thirty-year career, which charts his silent era days to the success he received in the latter part of his career in the 1950s.

Final Thoughts:

Mizoguchi’s exquisitely tragic ghost story is his finest cinematic achievement, and this restoration of Ugetsu is its best version, outside of a cinema, to date.

Film Review: ★★★★½/☆☆☆☆☆

Disc Review: ★★★★½/☆☆☆☆☆