Reviews

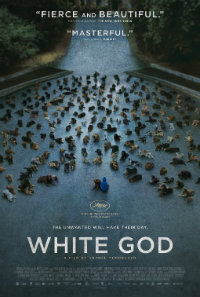

White God | Review

All Dogs Go To: Mundruczo’s Sad Trumpet Ballad an Allegory of Inhumanity

Terminology is key to deciphering the shaggy subtext of Kornel Mundruczo’s allegorical film, White God, a film about the monstrousness that humans create due to a seeming hardwired cruelty that demands the obliteration of difference and diversity. Technically assured and boasting an impressive array of multiple canine performances, Mundruczo’s interspecial balancing act is unfortunately a bit one sided, with his human characters are relayed less effectively and generally as one-note. Though it speeds through its two hour running time, it still manages to feel a bit too long in the tooth, and perhaps less time spent on the overwhelmingly execrable humans tends to lessen the empathetic impact.

Terminology is key to deciphering the shaggy subtext of Kornel Mundruczo’s allegorical film, White God, a film about the monstrousness that humans create due to a seeming hardwired cruelty that demands the obliteration of difference and diversity. Technically assured and boasting an impressive array of multiple canine performances, Mundruczo’s interspecial balancing act is unfortunately a bit one sided, with his human characters are relayed less effectively and generally as one-note. Though it speeds through its two hour running time, it still manages to feel a bit too long in the tooth, and perhaps less time spent on the overwhelmingly execrable humans tends to lessen the empathetic impact.

Thirteen year old trumpet player Lili (Zsofia Psotta) is forced to live with her surly father Sandor Zsoter) after her mother leaves with her new beau. Lili is accompanied by her dog, Hagen, who her father reluctantly agrees can come with. But upon entering his apartment building, it’s immediately apparent that Hagen won’t be allowed to stay as nosy, clamoring neighbors inform them that mixed breed dogs are about to be banned. Authorities show up the next morning to look for Hagen as a neighbor (erroneously) claimed to have been bitten. Unable to leave the dog alone, Lili sneaks him into band practice, but the dog disrupts rehearsal causing the extreme ire of the conductor. Forced outside, Lili walks aimlessly with the dog, causing her irate father to abandon him on the streets.

Language becomes important in its relation to the human tendency for classification. Immediately Hagen’s pedigree becomes central to the conceit, an overtly bitchy neighbor of Lili’s father announcing a new law stating non pure-bred canines must be registered, which is accompanied with a certain price tag. This sets up a rather effective class divide, as those with blue collar salaries can hardly afford the price and upkeep of pure bred animals and are deterred from having to pay erroneous fees for more affordable pets. As an object of the working class human (much like children), Hagen is without any sort of protection, a victim vulnerable to a sea of apathy and cruelty. His ‘mixed’ status is consistently mentioned, to the point where Lili corrects a classmate, preferring the term ‘mixed breed’ to the demeaning ‘mutt.’ But Mundruczo’s deliberate metaphor begins to sour in the words of its humans, with characters constantly commenting on Hagen’s gentle demeanor on his road to perdition. “It doesn’t hate us,” a dog catcher comments. “You’ve still got a heart,” comments a cruel man that buys Hagen to be a fighting dog.

Meanwhile, Lili begins to undergo a sort of transformation on her own, albeit a wholly less interesting one. As performed by newcomer Zsofia Psotta, she’s the most consistent human presence, a believably sullen adolescent who hasn’t learned yet how to protect what she loves, which gives rise to significant frustration as we’re forced to watch her abandon Hagen on the streets at her father’s behest. And while the destruction of ‘the other’ represents the event which allows a majority at odds the ability to reunite, as signified by Lili’s temperamental father transforming into a likeable human being, it’s an unprecedented and unbelievably handled change.

Hagen’s increasingly desperate journey through the Hungarian urban wasteland cuts a near epic swath through miserabilism, evading vengeful dog catchers, falling into the clutches of a repugnant homeless man, then sold into slavery before escaping a dog fighting arena and ending up on the kill list of a dog pound, whose more empathetic owner seems like the hard hearted woman Lili herself might eventually become. As Hagen watches his comrade put to sleep, he’s been placed in a private room where he idly glances at “Tom and Jerry” playing on a television set, as if to signify the hollowed entertainment we allow ourselves to be distracted with while all around us savagery occurs.

Premiering at the Un Certain Regard section of the 2014 Cannes Film Festival, the title picked up the top prize of the sidebar (in a lineup that included Jauja and Force Majeure) and has gone on to receive wide acclaim on its festival circuit journey. Several have already pointed out the canine connection with Sam Fuller’s 1982 film White Dog, which documents an instance where a dog was trained to attack black people, and which Mundruczo’s title inverts. That great white god, representative of the entity responsible for human creation in several popular belief systems, has trained us to turn on each other for our differences, obliterate and pillage based on race, class, gender, and as Mundruczo’s allegory extends the argument, to other species. And so it is that Mundruczo’s latest, which very much continues his fascination with the cruelties humans exact upon one another, whether it be his sexually tinged retelling of Joan of Arc with Johanna (2005), an incestuous rural relationship in Delta (2008), or a reimagining of Mary Shelley’s timeless text in Tender Son: The Frankenstein Project (2010), manages to retain its powerful emotional core despite some less subtle tendencies, ending on a powerful final shot of peace made all the more memorably sorrowful for its ability to connote its fleetingness.

★★★/☆☆☆☆☆

Los Angeles based Nicholas Bell is IONCINEMA.com's Chief Film Critic and covers film festivals such as Sundance, Berlin, Cannes and TIFF. He is part of the critic groups on Rotten Tomatoes, The Los Angeles Film Critics Association (LAFCA), the Online Film Critics Society (OFCS) and GALECA. His top 3 for 2021: France (Bruno Dumont), Passing (Rebecca Hall) and Nightmare Alley (Guillermo Del Toro). He was a jury member at the 2019 Cleveland International Film Festival.