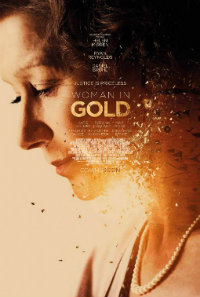

All that Glitters: Curtis Traps Compelling Kernel in Avalanche of Schmaltz

British television alum Simon Curtis graduated to feature filmmaking in 2011 with the incredibly problematic My Week with Marilyn. Apparently, whatever its faults, they were easy to overlook, as the film nabbed a number of critics’ choice awards, along with prestigious BAFTA and Academy Award nominations. Unfortunately, his penchant for mawkishness has showed no sides of abatement in his follow-up feature, Woman in Gold, also based on compelling true events but at least portraying subjects that feel imbued with less drastic measures of caricature since they aren’t ingrained in cultural pop subconscious with such sacred fury.

British television alum Simon Curtis graduated to feature filmmaking in 2011 with the incredibly problematic My Week with Marilyn. Apparently, whatever its faults, they were easy to overlook, as the film nabbed a number of critics’ choice awards, along with prestigious BAFTA and Academy Award nominations. Unfortunately, his penchant for mawkishness has showed no sides of abatement in his follow-up feature, Woman in Gold, also based on compelling true events but at least portraying subjects that feel imbued with less drastic measures of caricature since they aren’t ingrained in cultural pop subconscious with such sacred fury.

In the late 1990s, the Austrian government began to revamp its art restitution laws in reference to victims of WWII. Upon the death of her sister, Maria Altmann (Helen Mirren), an elderly Los Angeles shop keeper who had fled Austria sixty years prior to escape the Nazis, discovers letters among her sister’s belongings documenting unsuccessful attempts to reclaim their family’s collection of Klimt paintings, in particular the famed Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I, which was a painting of their aunt. With the help of a friend’s (Frances Fisher) son, Randol Schoenberg (Ryan Reynolds), grandson of the famed composer, Maria sets off to Austria to reclaim the paintings. She’s met with considerable opposition by the Austrian government, which eventually leads to a struggle that sees the case brought before the U.S. Supreme Court and then back to Austria for arbitration.

If Dame Helen Mirren has any inkling of the deliberate and often grating amount of posturing going on all around her, she never lets it show, portraying Maria Altmann with a gravitas that does wonders to overcome the obvious sentimentality (though, if judging from all the sniffling in the audience, Curtis certainly accomplishes what he set out to do).

Mirren often throws herself into uncustomary roles, like that of an Israeli Mossad agent in The Debt (2010) or a Hungarian maid in Istvan Szabo’s The Door. Initially, her Maria Altmann appears to be in this similar vein, donning brown contacts, an Austrian accent and fading curls, she still retains that impressive ability to command believability even when that seems impossible. As one can imagine, Ryan Reynolds (fitted with crooked teeth to give him just the right amount of ‘normality’) feels much less suited to be her co-star, wading through a porridge of sticky, noble-hearted monologues, as a man forever trying to outrun the own impossible shadows of the Schoenberg lineage, sharing clunky scenes with a distracting Katie Holmes, here to provide him with children and soothing support whenever we need to see his character struggling. And then there are those evil Austrians, engaged in malicious machinations to hold on to those Klimt paintings for dear life, with lone ranger journalist Daniel Bruhl on hand to valiantly support them because he has his own big secret (revealed with the subtlety of a brick through a window). Meanwhile, Charles Dance makes another appearance as a bitchy boss (see recent turns in The Imitation Game and Dracula Untold), and yeah, blink and you’ll miss Mortiz Bleibtreu as Klimt in the opening sequence.

Curtis is working from a first time screenplay penned by actor Alexi Kaye Campbell, and the amateurish flair seems obvious, for the film displays a tired, endlessly recycled rhetoric about how these films documenting the righting of injustices are portrayed. Depictions of WWII horrors are equally cliché, even as they do manage a certain sense of malicious unease (for, as humans, how can we not automatically be repelled?) and the constant flashbacks through Maria’s memory, filmed in direct, chromatically stylized opposition to the saturated palette of late 90’s Los Angeles, seem like obvious bids of convenient hindsight, such as how she came to eschew German for English. Several distracting bits in the Los Angeles sequences abound, for instance, the presence of Guardians of the Galaxy billboards evident as Maria and Randol drive down Wilshire Avenue even though the events take place circa late 1998/1999.

While Maria Altmann’s struggle to obtain the famed Klimt painting, the Austrian Mona Lisa, is and remains a compelling account of one of WWII’s last victims (a reference to stolen artwork made by Ronald Lauder, the man eager to secure the painting, which he purchased for 135 million from Altmann, in an oddly wooden scene), it’s a pity that Curtis could only manage to force feed (as Altmann has to point out about the renaming of the portrait to Woman in Gold, ‘they stole her identity as well’), relying on easily discernable manipulation.

We’ve seen a cinematic resurgence in these war time artifacts, with George Clooney’s recent The Monuments Men (which is heavily indebted to Frankenheimer’s The Train, 1964) and the 2006 documentary The Rape of Europa, but perhaps we’ve tapped into generations too far removed from the horrific period, for many seem to forget that the terror of these events speaks for itself.

★★/☆☆☆☆☆