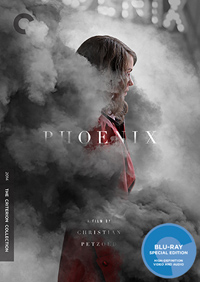

German auteur Christian Petzold makes his bow in the esteemed Criterion collection with his outstanding seventh feature, Phoenix, which is also his sixth title to feature his on-screen collaborator, Nina Hoss. Premiering at the 2014 Toronto International Film Festival, the title was released by Sundance Selects in July of 2015 and hustled over three million at the US domestic box office (tripling the success of his 2012 award winner, Barbara, which netted a million). Since his 2000 debut The State I Am In, the Berlin School alum has moved to the forefront of internationally renowned German auteurs, with many of his works serving as reconfigurations of previously filmed properties. Hoss gives a startlingly impressive performance as a Holocaust survivor entangled in a devious arrangement where love and hate resides within the same amorphous shadow.

German auteur Christian Petzold makes his bow in the esteemed Criterion collection with his outstanding seventh feature, Phoenix, which is also his sixth title to feature his on-screen collaborator, Nina Hoss. Premiering at the 2014 Toronto International Film Festival, the title was released by Sundance Selects in July of 2015 and hustled over three million at the US domestic box office (tripling the success of his 2012 award winner, Barbara, which netted a million). Since his 2000 debut The State I Am In, the Berlin School alum has moved to the forefront of internationally renowned German auteurs, with many of his works serving as reconfigurations of previously filmed properties. Hoss gives a startlingly impressive performance as a Holocaust survivor entangled in a devious arrangement where love and hate resides within the same amorphous shadow.

While that film examined a predicament in early 80’s East Berlin, Petzold reaches farther back into the troubled tumultuousness of Germany history with his latest feature, set shortly after the end of WWII. The surviving members of Germany’s populace are forced to contend with restructuring via the help of outside military sources, as well as dealing with the returning survivors of the concentration camps. Like most of Petzold’s films, he borrows from the essence of vintage materials, and this one is no exception, based on a novel Hubert Monteilhet, which had previously been filmed as a 1965 Euro-tinged noir starring Ingrid Thulin and Maximilian Schell, directed by J. Lee Thompson called Return From the Ashes. But the resemblances between the films are spare (Petzold cuts out a major character altogether from the source text, for instance), and we’re left with a brooding, masterful portrait of socially sanctioned deception and the fallout of an insidious, unforgivable betrayal.

Lene (Nina Kunzendorf) has somehow managed to locate her old friend, the singer Nelly Lenz (Nina Hoss) in the bombed out ruins of war torn Berlin, returning the Auschwitz survivor to her sheltered apartment in Berlin. Nelly’s face has been decimated by a bullet, requiring her face to be reconstructed. She wishes to look like herself again, but the dubious surgeon scoffs, suggesting popular stars of the time to be modeled after instead, such as Zarah Leander. The shell shocked woman is numb to her friend’s insistent plans to move to Palestine, instead wishing to find news of her husband, piano player Johnny (Ronald Zehrfeld). Only Lene is well aware Johnny informed the Nazi’s of Nelly’s whereabouts, information she was able to puzzle together based on divorce papers she stumbled upon.

Upon hearing he is alive and well, Nelly seeks him out as soon as her face is healed. Except, he doesn’t recognize her. Instead, he thinks this new version of Nelly is a stranger happening to resemble his wife, and so he approaches her asking her to pose as the dead singer so he can obtain her sizeable inheritance, something he was unable to do because his wife’s corpse was never recovered.

From the moment we glance at Hoss’s large, haunted eyes, Phoenix hooks us into a meditative character study built almost entirely around the tortured, blindly faithful feelings of a betrayed woman. Petzold reunites Hoss and Zehrfeld, the romantically inclined pair of Barbara, re-configured almost as a cruel joke here. And Phoenix has volumes to say as concerns reflections, identity, and persona, motifs which have earned it comparisons to works by masters like Hitchcock and his eventual thematic protégé, De Palma. But besides its superficial resemblance to something like Eyes Without a Face and its fantastical surgical transformation, Petzold dresses his film in tones more similar to classic film noirs dealing with ‘stolen’ identities, like No Man of Her Own (1950) or Robert Wise’s The House on Telegraph Hill, in which Valentina Cortese poses as a concentration camp survivor, assuming the identity and property of a friend.

And just as many noirs similarly explore the notion of transformation, this is the theme at the heart of Phoenix, as its title would indicate. Those unable to adapt to the present die out, like the film’s only other sympathetic character Lene, who comments she is ‘more drawn to the dead,’ and can see no future in a current world. Tellingly, terminology is teased, in reference to Nelly’s new face, a ‘re-creation’ rather than ‘re-construction.’ Her destroyed visage, granted a polished, brand new veneer after the fall-out has cleared, is a metaphor for Germany’s dreary, paralyzed period during this reconstruction.

Petzold grants us a seedy nightclub as the film’s site of re-introduction for Nelly and Johnny, sharing the film’s title and lit with hellish red and shadowy black pools of forbidding light. In one sequence, we catch the trailing words of the singers inside, crooning “Berlin by night,” while Nelly is bathed in these tones. Germany is literally a rotting corpse, Lena’s gruff maid remarking about the problem of the flies no one seems to be talking about.

Petzold is examining an utterly unique place and time, a ground zero attempting to rise from the rubble, the wounds still cracked, oozing, bleeding. As far as these chronicles go, Petzold is demure with the carnage. But as Lena comments about a revolver, “sometimes just showing it is enough.” Indeed, it is, and Phoenix reconstitutes unappealing truths about human nature, including the inability for people to look beyond merely seeing what it is they wish to see.

Add to this the comparative value of Hoss’ role in 2008’s Woman in Berlin from Max Faberbock, an adaptation of the famed diary by Anonyma, detailing the equally unsavory experiences a German woman underwent during the liberation, and you have a harrowingly uncomfortable double feature on your hands.

Hoss, also a talented singer, croons “Speak Low” late in the film, the accompanying piano player stops abruptly, and for good reason. She carries on to the end of the tune, a chilling, goosebumps inducing moment of spectacular emotional resonance. She’s a beautiful, reconstructed creature, but scarred eternally by the fire, marked forever by the ashes that have continued to shape and inform our understanding of mankind’s dreadful capacity for careless evil, banal and otherwise.

Disc Review:

Criterion presents the title in a 2K digital transfer with 5.1 surround DTS-HD Master Audio soundtrack. Picture and sound quality are exceptional, and Petzold’s regular DP Hans Fromm fashions a hellish, neon lit rubble out of bombed-out Berlin as the landscape for Nelly’s perverted resurrection (an equal to his prior period piece with Petzold, the equally impassioned Barbara). Criterion includes a new conversation between Petzold and Hoss, as well as an interview with Hans Fromm. Also included is a ‘making of’ documentary from 2014.

Christian Petzold and Nina Hoss:

This conversation was recorded in Berlin in January, 2016 and features Hoss and Petzold discussing their collaborative process as well as recurring themes in their work across six films. The twenty-five minute segment begins with a recollection of how they met and continues with their influence on one another.

Hans Fromm:

Also filmed in Berlin in January, 2016 for Criterion is this interview with Petzold’s regular DP Hans Fromm, who was worked with Petzold for two decades. The thirteen minute segment discusses his influences for the noir look of the film and the rarity of films set in Germany directly following WWW (the 1946 feature The Murderers Are Among Us is listed notably here).

The Making of Phoenix:

This documentary from 2014 features interviews with Petzold, production designer K.D. Gruber, and actors Nina Hoss, Nina Kunzendorf, and Ronald Zehrfeld. The twenty minute segment features discussions on the film’s design as well as the actors discussing the nature of their characters and their relationships to one another.

Final Review:

One of the best theatrical releases of 2015 gets a deserved, first-rate transfer with the Criterion Collection, a testament to the considerable talents of Petzold and star Nina Hoss.

Film Review: ★★★★/☆☆☆☆☆

Disc Review: ★★★★/☆☆☆☆☆