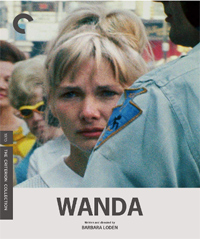

A director and a film unfortunately stymied shortly after its premiere, Barbara Loden’s Wanda (1970) remains a singularly unwavering portrait of neo-realistic gender identity which is finally brought to a platform whereby it can reclaim renown. Premiering out of the 1970 Venice Film Festival, Loden picked up the International Critics Award. One wonders what might have been possible had the film not premiered during the festival’s transitional period from 1969-1979, when there was no official ‘competition’ but only various sidebars sans a jury. Heretofore remembered as the estranged wife of director Elia Kazan, who cast Loden in 1960’s Wild River and the wild child sister to Warren Beatty in Splendor in the Grass (1961), the Tony winning actress would become the first woman to write, direct and star in her own production in 1970. However, the dismal, dismissive reception of the film, which concerns its titular character as a passive drifter who allows herself to be used, abused and eventually complicit in a failed bank robbery, sank the film into an obscurity. Revered by the French, particularly Marguerite Duras (who Amy Taubin points to in an exceptional insert essay for this new release), Loden can finally be recuperated as the cornerstone of feminist American indie cinema, still a glaring anomaly in its complex intersections of gender, class and American identity.

A director and a film unfortunately stymied shortly after its premiere, Barbara Loden’s Wanda (1970) remains a singularly unwavering portrait of neo-realistic gender identity which is finally brought to a platform whereby it can reclaim renown. Premiering out of the 1970 Venice Film Festival, Loden picked up the International Critics Award. One wonders what might have been possible had the film not premiered during the festival’s transitional period from 1969-1979, when there was no official ‘competition’ but only various sidebars sans a jury. Heretofore remembered as the estranged wife of director Elia Kazan, who cast Loden in 1960’s Wild River and the wild child sister to Warren Beatty in Splendor in the Grass (1961), the Tony winning actress would become the first woman to write, direct and star in her own production in 1970. However, the dismal, dismissive reception of the film, which concerns its titular character as a passive drifter who allows herself to be used, abused and eventually complicit in a failed bank robbery, sank the film into an obscurity. Revered by the French, particularly Marguerite Duras (who Amy Taubin points to in an exceptional insert essay for this new release), Loden can finally be recuperated as the cornerstone of feminist American indie cinema, still a glaring anomaly in its complex intersections of gender, class and American identity.

Wanda (Loden), a coal miner’s daughter in Scranton, Pennsylvania, has entered a tailspin. Crashing on a friend’s couch, she sets her in rollers on the morning of her divorce hearing, which she’s late for after visiting her father at work to ask for some money. Disinterested in sharing custody with her children, she mumbles to the judge they’d be better off with their father and his new girlfriend. Making a modest attempt to return to work at a dress factory, where her sewing skills left something to be desired, Wanda drifts into the arms of a traveling salesman, who eventually ditches her as fast as he picked her up. Ducking into a Spanish language cinema, she falls asleep, only to find her money’s been stolen. Wandering into a nearby bar and arguing her way into using the toilet, she neglects to realize she’s interrupted a robbery. She’s ignorant about this faux pas until the next day, having spent the night with Mr. Dennis (Michael Higgins), who she mistook for the bar owner. Not long after, she finds herself involved in the man’s scheme to rob a bank, training her to drive the getaway car. At first adamantly denying her ability, Mr. Dennis convinces her she can and will help him, which gives her a modicum of purpose.

Wanda isn’t so much a rectification to the hyper-stylized aggression of Arthur Penn’s Bonnie & Clyde (1967), the classic gangster epic which ushered in the hallowed age of the New American Cinema, as it is a powerful countermeasure in its representation of trauma and identity. As such, they’re interesting coincidental counterparts (unlike, say, Ken Russell’s 1991 Whore which was meant as a direct critique of the glossy prostitution in Pretty Woman, 1990), especially considering Loden’s curious intersections with Kazan and Faye Dunaway (whose character in Kazan’s 1969 The Arrangement is based on Loden).

But what to do with the aggravating passivity of Wanda, a woman who seems resigned to her own victimhood rather than attempt to calibrate any agency? Certainly, there’s frustration to be had in witnessing her descent into a criminal underworld, significantly at a moment where she untethers herself from the domestic manacle she’s previously escaped. And yet, Loden eschews any of the aggrandizing hand-wringing which accompanies the scandalous perversion of assigned feminine gender norms.

She’s neither the full-tilt cataclysm of Gena Rowlands in A Woman Under the Influence (1974) or even the apologetic, reformed nymphet of Clouzet’s recently restored La Verite (1960)—although the cultural dismissal of Wanda as merely a slut mirrors the castigation of the Bardot character from Clouzet. As Taubin also points out, Chantal Akerman’s Jeanne Dielman, 23 Quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles is probably the closest anyone has come to achieving what Loden does with Wanda in the collapsing of character and actual persona. Arguably, Polish director Agnieszka Smoczynska’s 2018 title Fugue plays like the nightmare inverse of Wanda, whereby a woman is forced to a return home to a husband and child she has no memory of or love for.

There’s an overwhelmingly palpable sense of stupor in Wanda, with Loden drifting haphazardly in and out of cognition as to what’s going on. With a marvelously subtle and quiet expressiveness, her performance is captured through the painstaking lens of Nicholas Proferes. Small facial tics and gestures reflect a woman who has yet to discover herself but believes she must depend on the kindness of strangers (i.e., men) to get by. It’s no wonder Isabelle Huppert was a champion of the film, (who assisted with the distribution of the film’s French theatrical release in 2004) as Loden conveys a similar sense of inscrutability, commanding us to search her face for traces of the emotional vortex behind it.

Incredibly malleable, her appearance becomes a point of contention to her haphazard warden, a Paul Schrader-ish Michael Higgins (who Huppert reads as a metaphor for Kazan and the Hollywood film industry), demanding she wear a dress and do something about her hair (which results in a flower headband so ill-thought it looks like a prop worn by Amy Sedaris as Jerri Blank in Strangers with Candy).

Her veritable fugue state speaks to a conditioned subjugation, the resulting trauma of which is rarely seen without the aid of grand hysterical gestures. Nowhere is this perhaps more evident than in a final touch of quiet heartbreak as we witness Wanda led to a remote location by an amorous man in uniform. She seems paralyzed, still reeling from the failed bank robbery she just barely avoided being killed in. As he groans and pants on her, assuming her stillness equates to consensuality, she begins to kick and scream, awakened to the scenario we all assume she should have predicted. As much as it as a glaring portrayal of complex facets of victimization, it also the first moment where Wanda breaks free of another yoke. And as we leave her, sitting glassy eyed in yet another bar with a group of rambunctious strangers, perhaps we can at least imagine not all is lost for Wanda, yet.

Disc Review:

Criterion presents Wanda as a new 2K digital restoration, made possible by the UCLA Film & Television Archive, The Film Foundation and Gucci. With a transfer in 1.37:1 with monaural soundtrack, the release retains the grainy feel from the original 16mm negative, though picture and sound quality are clear and concise from this 2010 restoration.

I Am Wanda:

This hour-long 1980 documentary from Katja Raganelli features an interview with Loden as well as brief snippets of DP Nicholas T. Proferes and acting teacher Paul Mann.

The Dick Cavett Show:

Loden was featured on this March 4, 1971 episode of The Dick Cavett Show for the promotion of Wanda.

Barbara Loden at the AFI:

Loden spoke as part of the Harold Lloyd Master Seminar series at the American Film Institute in this hour-long recording from April 2, 1971 in which she speaks on the challenges of making one’s first film.

The Frontier Experience:

This half-hour educational film about a pioneer woman struggling to survive with her family on the Kansas prairie is also included.

Final Thoughts:

At last available in all her quiet, despondent glory – To-Wanda.

Film Rating: ★★★★½/☆☆☆☆☆

Disc Rating: ★★★★/☆☆☆☆☆