Lady Sings the Hues: Rees Returns to Resurrect the Star of Blues Singer

Many may not be immediately familiar with the name Bessie Smith, an incredibly talented and enigmatic blues singer from the 1920s and 30s, whose accomplishments may have lapsed into obscurity outside of the aficionado’s realm. Until now. Returning with her sophomore feature after her powerful 2011 debut Pariah, Dee Rees throws herself into the prickly wiles of the biopic with Bessie for HBO Films. Following in the footsteps of several auteurs that have developed projects with the network, often imbued with those exact details of real life personalities that made their lives so startling in the first place (like Soderbergh’s 2013 Liberace film, Behind the Candelabra), on the surface, Rees gracefully navigates the period with graceful resilience. Until we start to realize there’s still too much we don’t know about Bessie Smith. Eschewing, or more aptly, steadfastly opposed to the general exposition that provides the skeletal structure of the what, why, and when of the very important who at its center, Rees, with screenwriters Bettina Gilois and Christopher Cleveland, paint Bessie Smith into a pretty corner.

Many may not be immediately familiar with the name Bessie Smith, an incredibly talented and enigmatic blues singer from the 1920s and 30s, whose accomplishments may have lapsed into obscurity outside of the aficionado’s realm. Until now. Returning with her sophomore feature after her powerful 2011 debut Pariah, Dee Rees throws herself into the prickly wiles of the biopic with Bessie for HBO Films. Following in the footsteps of several auteurs that have developed projects with the network, often imbued with those exact details of real life personalities that made their lives so startling in the first place (like Soderbergh’s 2013 Liberace film, Behind the Candelabra), on the surface, Rees gracefully navigates the period with graceful resilience. Until we start to realize there’s still too much we don’t know about Bessie Smith. Eschewing, or more aptly, steadfastly opposed to the general exposition that provides the skeletal structure of the what, why, and when of the very important who at its center, Rees, with screenwriters Bettina Gilois and Christopher Cleveland, paint Bessie Smith into a pretty corner.

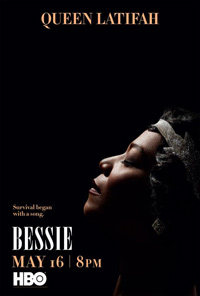

Beginning in 1913 Atlanta, up and coming blues singer Bessie Smith (Queen Latifah) struggles to gain respect in venues that prefer black women who weigh less with lighter skin tones. Formidable and self-determined, Bessie inserts herself into the company of Ma Rainey (Mo’Nique), a seasoned and famous personality who allows Bessie to travel with her troupe and foster her talent. Eventually, Bessie begins to outshine Rainey on her own stage, causing a dissolution between the performers. Branching out on her own and with her brother Clarence (Tory Kittles) as her manager, Bessie begins her own ascent. With her girlfriend Lucille (Tika Sumpter) at her side, Bessie acquires an eager male suitor, Jack Gee (Michael Kenneth Williams), a man who eventually marries and manages her before their relationship begins to crumble as well.

As the nonconformist, black, bisexual singer, there’s something nagging at the periphery of this handsome fantasy, namely all those difficulties and social hurdles Smith conquered to alight into the zeitgeist. It’s not that we need to see suffering to appreciate advancement, but since many are unaware of Smith, the film’s petty acknowledgments, including her lightly handled alcohol issues, avoid the kinds of confrontations where Smith would not have been able to usurp control. As opposed to Billie Holiday’s infamous drug abuse issues in Lady Sings the Blues (1972), Rees skirts too comfortably around unappealing instances.

But the actual elephant in the room has little to do with Rees. As Smith, Queen Latifah gives one of her most rounded performances, exuding traces of vulnerability often absent from her previous cinematic endeavors. This reaches a perpetual zenith when we find the star gazing upon herself in her dressing room mirror, stark naked. The camera lingers on Latifah, and it’s an arresting, bold moment. But whatever heights the actress reaches here, Bessie always feels like an empty victory. Unfair as it may be, Queen Latifah’s staunch refusal to address questions pertaining to her own sexual identity infects and taints this representation of the undaunted blues singer. If anything, Bessie feels like a rehearsed opportunity for Latifah to take advantage of a moment and perhaps finally come out—but whatever the case, the provocative representation of Bessie and the life she lived is only set up to be outshined by either Latifah’s continued silence on the matter or her eventual vocalization.

We watch Smith confront the KKK as they attempt to burn down the tent she’s performing in. We smirk at her dismissal of the disgusting writer Carl Van Vechten (Oliver Platt), a man she brazenly calls out for a remark on Langston Hughes with “Then who’s the best normal poet?” And it’s utterly refreshing to see such a strong personality refuse to be victimized for her race, gender, or sexual orientation (even if the film declaws her surroundings). But it’s hard to imagine that a woman like Smith, depicted as staunchly nonconformist, wouldn’t be rolling in her grave to see Queen Latifah depicting her onscreen.

Other cast members are uniformly shaped, though Michael Kenneth Williams tends to stand out as Bessie’s eventual husband and staunch supporter. As her girlfriend, the beautiful Tika Sumpter is too distracting for the period, even if she is a brightly glowing presence whenever on-screen. Mike Epps appears late in the film as a bootlegger who falls for Bessie, but their relationship is related in paraphrase.

Blink and you’ll miss Charles S. Dutton, but the film serves to be a better comeback for the talents of Mo’Nique as Ma Rainey. Though the role isn’t much of a stretch for the actress, there’s a nagging suspicion that Rainey’s story is in greater need of cinematic representation than Bessie’s. A scene that finds Rainey following a performance in male drag is oddly effective, as both she and Smith kiki with a bevy of beautiful women. She advises the tentative Smith, nervous to be seen gay in public, “they have to prove it on you.”

Age progression issues tend to distract when it comes to Latifah and Khandi Alexander, especially considering Rees’ refusal to adhere to the standards of the biopic. This maintains a strange mixture of innovation and frustration as the film draws on, especially concerning more important instances from her life, such as the adoption of a child, and the onset of the Great Depression. Her star on the rise again in the third act, we’re treated to a theater manager (Bryan Greenberg) scouting her out for her inclusion in a racially integrated show, and moments later she performs to rousing applause from a white audience while the camera pans up to the blacks in the balcony.

With too much unexplained, these odd jumps and cuts tend to drain the emotional punch of Bessie, especially as we’re paraded through only her overwhelmingly successful moments, made to look deliriously easy to achieve. To be shackled to the narrative of a real life personality is difficult material to represent on screen, even with the freedom allotted by HBO. DoP Jeff Jur doesn’t achieve the visual beauty that Bradford Young created on Rees’ Pariah, but the film opens mysteriously, on the stage-lit upturned face of Bessie in a feather boa and Cleopatra wig. Moments later, her shadow haunts the doorway to her empty home, a specter on the periphery of her own story. There are several moments of innovative visuals in Bessie, a sometimes powerful glance at a trailblazer deserving of greater credit.

Reviewed on May 09, 2015 via a Film Independent screening at LACMA w/Elvis Mitchell moderating a Q+A with director Dee Rees and star Queen Latifah.

★★★/☆☆☆☆☆