Requiem for a Cave Man: Franco’s McCarthy Adaptation Displays Growth

On a similar directorial trajectory as, let’s say, Joe Swanberg, where quality vs. quantity tends to have adversely affected the end product of many a project, actor/screenwriter/director James Franco has shown surprising growth with his latest directorial effort to hit theaters, an adaptation of Cormac McCarthy’s Child of God. Begrudging as many may be toward the film, especially rabidly committed fans of the source material, one has to admit that considerable growth has been evidenced in this recent sampling of Franco’s cycle-stomping over his literary idols, veering haphazardly over Faulkner, McCarthy, and Bukowski. Certainly, there are a few issues to haggle over, but there’s a captivating performance and a queasy ambience to the film that at least makes it a sober sort of hillbilly horror. Yes, perhaps this is sacrilege to those worshipping at the author’s altar, but this is one apostle’s offering that’s at least worth a look.

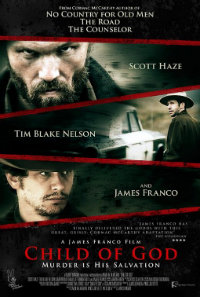

After the death of his father, Lester Ballard (Scott Haze) is left to fend for himself in the backwoods of Tennessee. His father’s land is taken from him and auctioned off, driving the troubled young man off into the wilderness. While the local Sheriff (Tim Blake Nelson) and his deputy (Jim Parrack) do their best to reign him in, Ballard’s already troubled mental state unravels quickly, and his innate wish for companionship sees the lonely man engage in terrible activities after a chance encounter with a pair of bodies redulting from a suicide pact.

It’s a bit flabbergasting to realize that DP Christine Voros has been along for the ride on several of Franco’s features. While Sal (2011) felt like a student film project and As I Lay Dying (2013) was a curious and sometimes tepid attempt at adapting a difficult Faulkner text, artistry and experimentation coalesce a bit more seamlessly this time around, at least to the extent of focusing on the film rather than distracting choices. Voros’ digital cinematography still feels somewhat aimless, but it seems less a shapeless time-wasting flourish this time around.

Yet some of the more glaring errors in Child of God concern a lack of attention to detail concerning Lester Ballard. Scott Haze, despite the grit and grime, sometimes appear too polished, especially as concerns his very white, very clean, very nice teeth, protruding as they may be. This is even more surprising concerning the very memorable maw of Tim Blake Nelson in As I Lay Dying. It’s something very distracting, which is a pity considering Haze is often captivating in a performance that dominates nearly every frame of the film, trailing off as he mutters to himself, ogling his macabre ‘treasures’ as he stomps around the backwoods like a mixture of Gollum and Wolf Man.

But Haze’s performance feels sometimes handicapped by the film’s confused tone. One assumes Franco is going for black comedy, except that Child of God doesn’t play to those strengths. Instead, the films walks the middle of the road, where we’re probably meant to chuckle in discomfort at Ballard’s actions, which culminates in a coterie of corpses he has sex with, and also feel some sort of pity for his existence as a victim of circumstance. And, in fact, we never get to know much about him, just tidbits picked up here and there from run-ins with Nelson’s gruff Sheriff.

Franco himself makes a rather unnecessary cameo during a witch hunt for the unassuming serial killer. This culminates in the film’s final moments of appropriate brevity. While Franco’s attraction to experimenting with visual narrative has more of a resounding payoff, the grotesque strangeness of the material isn’t presented as powerfully as it could have been.

★★½/☆☆☆☆☆