Mad as Hell: Campos Paints a Moving, Psychological Portrait of Sensational Subject

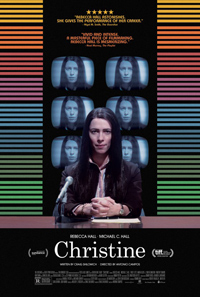

For his third and most psychologically complex feature to date, Antonio Campos presents a series of instances leading up to the tragic death of news journalist Christine Chubbuck, a Floridian woman who infamously committed suicide on live television in 1974. The incident was partially the inspiration for the classic 1976 film Network, but the Chubbuck tragedy eventually became a journalistic case study, eventually a footnote in the passing decades, eclipsed by more sensational, more horrific examples of the increasingly lurid direction of news media. Instead of capitalizing on Chubbuck’s inevitable demise, Campos and screenwriter Craig Shilowich (the producer making his screenwriting debut), craft an expertly moderated character study for Christine, studiously and painstakingly portrayed by Rebecca Hall in what surely stands as her most accomplished screen performance to date.

For his third and most psychologically complex feature to date, Antonio Campos presents a series of instances leading up to the tragic death of news journalist Christine Chubbuck, a Floridian woman who infamously committed suicide on live television in 1974. The incident was partially the inspiration for the classic 1976 film Network, but the Chubbuck tragedy eventually became a journalistic case study, eventually a footnote in the passing decades, eclipsed by more sensational, more horrific examples of the increasingly lurid direction of news media. Instead of capitalizing on Chubbuck’s inevitable demise, Campos and screenwriter Craig Shilowich (the producer making his screenwriting debut), craft an expertly moderated character study for Christine, studiously and painstakingly portrayed by Rebecca Hall in what surely stands as her most accomplished screen performance to date.

In 1974 Sarasota, Florida, 29-year-old news reporter Christine Chubbuck (Hall) persistently pursues her dreams of becoming notable in her field, a feat which seems hampered by her uncomfortable home life living with her mother (J. Smith Cameron), unrequited feelings for her news anchor colleague (Michael C. Hall), and a boss (Tracy Letts) frustrated with what he believes to be her feminist agenda. As we learn more about Christine’s increasingly erratic emotional state, we try to make sense of what brought such a promising, driven woman to such a devastating precipice.

Sympathetic without being melodramatic, we gaze at a woman whose hopes and dreams slowly evaporate, tuning into a culture increasingly obsessed with negativity and apathy. DP Joe Anderson captures a crumbling period environment filled with off-greens and dingy yellows, a smoky haze filtering through the interiors. Precise details are captured within every frame, from Christine’s peripheral environment (the sounds of the hospital, for instance in her ventriloquist performances administered to ailing children) to a myriad of physical tics of Christine’s awkward, rigid public persona.

Hall is superb as a social misfit, painted into a corner of her own considerable ideals and integrity. With Joan Crawford painted slashes for eyebrows, we first observe her deconstructing televised images of herself, self-deprecating about her posture—-is she too sympathetic interviewing her subjects? It’s the first of many impossible standards we realize Christine holds herself to, aggravated even more by those kind enough to realize she’s in need of a friend (presented in beautiful supporting turns from Maria Dizzia and Michael C. Hall).

As her ornery editor points out, played with dismissive aplomb by playwright Tracy Letts, Christine is perhaps the brightest member on his staff who can’t get out of her own head. Of course, it’s also a critical period for women’s rights, with Chubbuck inhabiting a male dominated environment, perhaps one of several excuses she uses to explain her lack of progress. But Anderson’s camera gazes upon her indifferently, sometimes coldly.

Hall is hypnotic, every little movement capturing a woman constantly on edge, engaged in an inauthentic persona, the woman she thinks the world will most likely embrace. Campos peppers the film with moments so awkward they become darkly comic, such as when Chubbuck approaches a couple at a bar after observing they seem to be in love, or a taped feature of herself ‘acting,’ something she whips up as a ploy to score a lead story. As all those kind enough around her suggest methods of self-help, the film takes on a level of doomed heartbreak as regards Christine, who realizes she will never be able to have the occupation she desires unless she conforms to standards she believes beneath the dignity of the profession.

J. Smith Cameron (from Lonergan’s masterpiece, Margaret, 2011), stars as Chubbuck’s loving mother. One wishes Campos had devoted a bit more time to this terrifically complex relationship. Enabling and most certainly toxic, it’s also a tender, endearing portrait of a mother and daughter, recalling, strangely, something like Brian De Palma’s adaptation of Carrie (1976). As we rush into the inevitable, Campos captures a perfect balance of emotional distress. Following his 2008 debut Afterschool and 2012’s American sociopath in Paris study Simon Killer, Campos makes his most deliberately steadfast effort to date, combining the troubled prowess of a protagonist with a cultural fascination of invasive media.

Coincidentally, his film arrives at the same time as a new documentary on Chubbuck by Robert Greene, Kate Plays Christine, an experimental portrait of the troubled journalist. While posing an opposing angle on the nature of the tragedy and the usefulness of depicting it, each will doubtlessly affect audiences in different ways. What Campos accomplishes is a portrait of a social misfit who ends her life in an incredibly tragic, distressing way (powerfully captured in the film’s closing moments) after struggling to reconcile the world she wants to the world that is. A cry for understanding and the importance of fostering authenticity over sensationalism or prized public opinion, Christine is an emotionally persuasive portrait of a human come undone, led expressively and memorably by Rebecca Hall.

★★★★/☆☆☆☆☆

Reviewed on January 23rd at the 2016 Sundance Film Festival – U.S. Dramatic Competition Programme. 119 Min.