Hearst & Foremost: Fincher Festoons the Neglected Glory of Herman Mankiewicz

The finicky methods of director David Fincher have themselves become nearly as iconic as the contemporary auteur himself. Breaking into feature filmmaking thirty years ago by inheriting the ill-fated (but underrated) franchise film Alien 3 in 1992, Fincher’s entry into the zeitgeist was trial by fire in a project he has vehemently divorced himself from. With only ten additional features to his name, the eleventh being his latest, Mank, it seems entirely apropos for Fincher’s mannered stylizations to recuperate the legacy of screenwriter Herman Mankiewicz.

The finicky methods of director David Fincher have themselves become nearly as iconic as the contemporary auteur himself. Breaking into feature filmmaking thirty years ago by inheriting the ill-fated (but underrated) franchise film Alien 3 in 1992, Fincher’s entry into the zeitgeist was trial by fire in a project he has vehemently divorced himself from. With only ten additional features to his name, the eleventh being his latest, Mank, it seems entirely apropos for Fincher’s mannered stylizations to recuperate the legacy of screenwriter Herman Mankiewicz.

Adapted from a screenplay by the filmmaker’s late father, Jack Fincher, it’s a testament to the director’s talents how the much-publicized strain of his filmmaking style (for several sequences, requiring his cast to undergo over a hundred takes) is nowhere in evidence in this strangely playful, but brooding snapshot of the rot beneath Hollywood’s façade of the 1930s and early 1940s.

Herman Mankiewicz was a notorious alcoholic. For those who know nothing of the man, his legacy, or his equally prolific family members (including younger brother Joseph L. Mankiewicz, screenwriter and eventual director of All About Eve, Suddenly, Last Summer and Cleopatra), the script does a fine job of formatting his idealism and eventual nihilism of the scribe.

Once a hobnobbing member of the Algonquin Round Table, passing reference to the anti-Hitler film he valiantly tried to get off the ground for years bolsters the attitudes on display regarding flashbacks to the 1934 governor election, which saw Democratic nominee Upton Sinclair railroaded by Republican Hollywood elitists. Fincher presents a world of reptilian backstabbers, from Arliss Howard’s pinched Louis B. Mayer, to the sinister gaze of Charles Dance (reuniting with Fincher from Alien 3) as William Randolph Hearst, eventually brought to life, despite the wishes of the inspiring man, under the thinly disguised odyssey of Orson Welles as Charles Foster Kane.

With a running time of over two hours, it’s a testament to editor Kirk Baxter (and DP Erik Messerschmidt) for splicing this together in a way which somehow clips along breathlessly despite elongated sequences of dialogue and a multitude of flashbacks. Fincher’s usual composers Trent Reznor and Atticus Finch, utilizing only period instrumentation, fade into the palette, as do many cast members who are simply around as passing support for the enjoyment or usefulness to Mank.

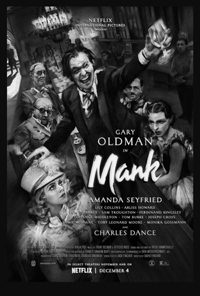

Tuppence Middleton as wife “Poor Sara,” and Lily Collins (who was the ingenue charged with reinvigorating Howard Hughes in Warren Beatty’s 2016 Rules Don’t Apply) as a British secretary, have little to do. Amanda Seyfried, on the other hand, has taken the much-portrayed Marion Davies (Melanie Griffith in RKO 281; Kirsten Dunst in The Cat’s Meow) and revitalized her as a complex myriad of opposing forces, her career forever eclipsed by her romance with “Pops,” but clearly realizing she perhaps sold her soul. And then, of course, Gary Oldman as Mank is the film’s shining hour, ornery and outspoken. His refusal to play by the rules and drink the Kool-Aid would cement his obscurity despite winning the Best Screenplay Academy Award for Citizen Kane (shared with Welles, portrayed via a decent impression courtesy of The Souvenir’s Tom Burke), the pinnacle of his career as well as the final nail in his professional coffin.

Fincher’s Mank is a somewhat morbid, at times formidably cold and clinical portrayal of an empire constantly reinventing itself to stay relevant. Designed as a visual evocation of Citizen Kane itself, Fincher seems to be appealing to the specter behind Welles’ personification of Hearst, inextricable from the energies and judgement of Mankiewicz. Ultimately, Fincher’s revelation is more a suggestion of how the faces may have changed but the human trials and tribulations remain the same between the uneasy bedfellows of politics and celebrity. As Fincher writes Mankiewicz himself saying, “You cannot capture a man’s entire life in two hours. All you can hope is to leave the impression of one.”

★★★½/☆☆☆☆☆