Portrait of a Lady: Laxton’s Mannered Version of Victoria Era Repression

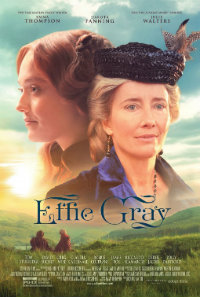

There’s well-meaningness to Effie Gray that makes it worthy of discussion, at least for how it attempts to frankly portray the sexual oppression of women in Victorian era England, an aspect often subtly rendered or left altogether untouched. As directed by Richard Laxton, best known for his made-for-television films of varying quality (An Englishman in New York; Burton & Taylor), there’s a sense that the somewhat ambitious emotions existing beneath all those stuffy costumes have been a tad oversimplified. Considering the screenplay was penned by Emma Thompson, who appears in a warmly attenuated supporting role, perhaps expectations are poised a bit high for a tale that’s both representative and also conveniently uncommon (this seems the only possible way for this film to reach a believable yet upbeat solution), as it relates a famous art world scandal through the perspective of its female player.

There’s well-meaningness to Effie Gray that makes it worthy of discussion, at least for how it attempts to frankly portray the sexual oppression of women in Victorian era England, an aspect often subtly rendered or left altogether untouched. As directed by Richard Laxton, best known for his made-for-television films of varying quality (An Englishman in New York; Burton & Taylor), there’s a sense that the somewhat ambitious emotions existing beneath all those stuffy costumes have been a tad oversimplified. Considering the screenplay was penned by Emma Thompson, who appears in a warmly attenuated supporting role, perhaps expectations are poised a bit high for a tale that’s both representative and also conveniently uncommon (this seems the only possible way for this film to reach a believable yet upbeat solution), as it relates a famous art world scandal through the perspective of its female player.

Victorian era art critic John Ruskin (Greg Wise) marries much younger Scotswoman Effie Gray (Dakota Fanning), against his mother’s (Julie Walters) fervent wishes. Apparently having known Effie since she was a child, they have a mildly friendly rapport, but upon their wedding night it is immediately apparent that he holds no sexual attraction for her. Eventually, he withdraws from her completely, absorbed by his work (he was a champion of J.M.W. Turner’s work, and Mike Leigh’s 2014 biopic of that artist bears striking similarities in its treatment of women as sexual objects), and thus belittles her, treating her more as a maidservant than a wife, which results in Effie developing a number of emotionally related manifestations of physical deterioration. Effie strikes a friendship with Lady Eastlake (Emma Thompson) at a formal dinner, and the accomplished socialite eventually helps Effie by introducing her to a lawyer, culminating in a landmark court case wherein the marriage was annulled.

As far as Victorian era protagonists are concerned, Effie is as sympathetically rendered as any. However, try as she might, Fanning’s performance always manages to seem rather ungainly, the task of a successful British accent sometimes lost in what often seems like a speech impediment. She certainly looks like an emotionally brutalized creature from the period and has taken great pains as far as appropriate mannerisms are concerned. But even successfully sympathetic, she’s still sometimes frustratingly distracting. The material is basically comparable to something like that of Henry James’ Portrait of a Lady, wherein an American woman who finds out her husband’s nature too late, but is far too broadly drawn to compete with a characterization like Isabel Archer.

At the same time, Effie Gray is a head above the demeaning fantasy of something like Tanya Wexler’s 2011 Hysteria. Instead, the emotional issues plaguing Effie and the dire physical manifestations of her mentally abusive relationship recall Alice Winocour’s Augustine. But in the third act Effie Gray stumbles over itself by injecting a convenient romance with Tom Sturridge, and whether true or not, is hardly as developed as it should be considering Thompson has taken deliberate pains to distract from Effie’s story with more sensational elements.

Emma Thompson plays the sort of life saving entity that also feels a bit too good to be true, but as usual, she’s a screen presence that manages to transcend the possible shortcomings of the role. This happens to be Thompson first serious screenplay for a feature film since her Oscar win for 1995’s Sense & Sensibility (since then, she penned the excellent HBO Mike Nichols’ directed Wit, and then those two Nanny McPhee films), and it feels underwhelming in comparison. But behind the scenes, Thompson’s passion project survived two lawsuits of plagiarism, which explains the lack of public championing of the title. It appears that perhaps too many people had to be appeased in order to make the final product, a shame considering what Thompson was initially attracted to still manages to be intact, albeit hampered.

A cadre of excellent yet underutilized Brits join Claudia Cardinale to fill out the supporting bits including a bitchy Julie Walters, Derek Jacobi, Robbie Coltrane, and David Suchet. Laxton seems intent on keeping the situation rather broadly and forcibly drawn as evidenced by moments like the vile Greg Wise’s humbling in front of his parents. Apparently, Ruskin was initially only nine years older than his wife, while Wise is nearly three decades older than Fanning, which results in an even more perverse portrait of a privileged man child, spoiled endlessly by his overly protective parents.

Overall, the sense of rather ceaseless suffocation at John Ruskin’s indefatigable coldness makes Effie Gray all black and white. And one can’t forget that Effie Gray’s inevitable redemption comes from the fact that she discovers a loophole in the system—the kind of loophole that seems more magical than logical, at least as far as the reality for most women of the distant and more modern eras can surely attest.

★★½/☆☆☆☆☆