Allegory of the Tree: Enyedi’s Masterful Meditation on Human Progress

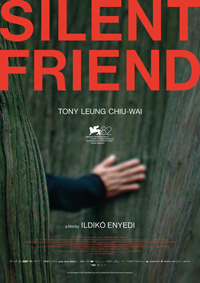

The metaphorical subtexts germinating to fruition through Ildikó Enyedi’s Silent Friend are formidable, even as, with humble simplicity, they profess to be enamored with the central figure of a tree. Returning to the more meditative realm which defined her 2017 Golden Bear winner On Body and Soul (Enyedi’s first feature after a near twenty-year absence), her latest holds a steady, tranquil gaze across three distinct periods (1908, 1972, 2020) spanning a century, its characters connected by their proximity to a sturdy gingko tree in a German botanical garden. In essence, it’s a film which examines progress through our ability to communicate not only with each other but the environment around us, suggesting self-actualization is achieved through our sometimes brief moments whereby harmony is reached by mutual grasping of our interconnectedness.

The metaphorical subtexts germinating to fruition through Ildikó Enyedi’s Silent Friend are formidable, even as, with humble simplicity, they profess to be enamored with the central figure of a tree. Returning to the more meditative realm which defined her 2017 Golden Bear winner On Body and Soul (Enyedi’s first feature after a near twenty-year absence), her latest holds a steady, tranquil gaze across three distinct periods (1908, 1972, 2020) spanning a century, its characters connected by their proximity to a sturdy gingko tree in a German botanical garden. In essence, it’s a film which examines progress through our ability to communicate not only with each other but the environment around us, suggesting self-actualization is achieved through our sometimes brief moments whereby harmony is reached by mutual grasping of our interconnectedness.

In essence, Silent Friend achieves the scientific version of the spiritual themes of John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress (1688), the distinct periods responding to the echoes of ancestors, a struggle allowing for the transformation of future generations. DP Gergely Palos (A Pigeon Sat on a Branch Reflecting on Existence, 2014) paints the medieval university town of Marburg in crisp black and white for the 1908 segment, which is also the most contentious period. Luna Wedler’s Grete must prove her worth despite the disregard of her gender, becoming the first woman to become enrolled at the university of Marburg. A prickly enrollment interview finds her battling with a predictably sexist panel of professors who are dismayed at having to consider the ‘weaker sex’ as equal. She’s grilled profusely by the theories of Swedish biologist Carl Linneaus, who developed an organization of plants through their reproductive processes. However, crude metaphors indicate the ignorance obscuring our shared understanding, as the procreation of plants is explained as a reflection of human counterpoints as an inferior mechanism compared to the religious cultural restraints of civilized society. The entrenched sexism of academia limits her abilities to succeed, and the necessity to find work and lodging to remain at the university finds her learning the trade of photography as an assistant to a kindly older gentleman (Martin Wuttke). The early days of this technology find a similar sense of obscuring, the images manipulated before they’re taken by lighting and once again after when they’re touched up to lessen unattractive qualities in their subjects. Both worlds which Grete’s immersed within deal with our resistance to truth and authenticity, but its her photography experience which justifies her bid to be included on a scientific expedition to Indonesia alongside a university assistant (Johannes Hegemann), with whom she shares a budding romance.

In 1972, students Gundula (Marlene Burow) and Hannes (Enzo Brumm), who share the same campus facility, also navigate a tentative attraction to one another. He’s a Rilke reading farm boy who disdains a past mired in economic agriculture while she’s conducting an experiment with a geranium in which she’s trying to record signals confirming the plant’s ability to communicate.

And then lastly, in 2020, in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, Tony Leung stars as a neuroscientist living alone on the abandoned campus. While his primary research has been documenting the brain functions of infants, wherein a tentative hypothesis suggests they view the world differently than adults (with what’s termed as ‘lantern-like’ consciousness rather than ‘spotlight’ consciousness, whereby other brain functions shut down as we focus on a singular stimulus), his isolation leads him to consider the gingko tree as subject after listening to a TED talk by Alice (Léa Seydoux), who extensively researches the way species of plants commune. He gets in touch with Alice, who agrees to guide him through his idea to record the tree’s signal patterns, which he believes may be similar to the data he’s compiled with infants. The two of them also share a flirtation from a distance.

We never see the romance consummated between the three couples across these distinct periods, but their courtship is the complex system of communication which will determine a potential actualization. In Leung’s segment, an ornery groundskeeper (Sylvester Groth) is thrown into the mix, sabotaging his dalliance with the tree, initially. But in reality, he’s also representative of the required harmony in any environment for mutually beneficial progress. Ironically, even as technological advances have allowed us the ability to more effectively communicate, knowledge does not equate to comprehension in practice.

With a vibrating audio palette and crisply edited finesse, Silent Friend becomes a sensuous immersive experience, flitting between observational instances of periods and characters, pollinating the audience with characteristics of its players with just enough information to keep desiring more. A structure similar to Bertrand Bonello’s 2023 masterpiece The Beast (also starring Seydoux) utilizes a same sense of how humankind’s essence travels beyond the mortality of the flesh. Whereas Bonello suggests a formidable despair regarding our eradication through technology, Enyedi leaves us merely at a moment in our modern progress to suggest we’re still as yet moving slowly toward a more sublime and serene existence.

Reviewed on September 6th at the 2025 Venice Film Festival (82nd edition) – In Competition. 145 Mins.

★★★★/☆☆☆☆☆