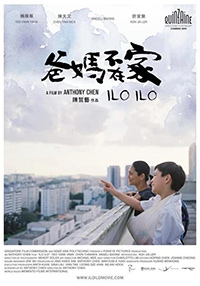

Singapore Slump: Economics Brushed Aside in Chen’s Gem Debut

In his autobiographical debut Ilo Ilo, young Singaporean helmer Anthony Chen delivers a beautifully simple story with hometown verve. Realism runs faithful to banal domestic life, but the low-key drama, set during the 1997 Asian financial crisis, comes alive with lighthearted humor. While there is a distinctive nineties aesthetic owed to lighting design, color sensitivity and an obligatory Tamagotchi cameo, the widely accessible narrative, through which racial and economic tensions are brilliantly woven, is far from passé.

In his autobiographical debut Ilo Ilo, young Singaporean helmer Anthony Chen delivers a beautifully simple story with hometown verve. Realism runs faithful to banal domestic life, but the low-key drama, set during the 1997 Asian financial crisis, comes alive with lighthearted humor. While there is a distinctive nineties aesthetic owed to lighting design, color sensitivity and an obligatory Tamagotchi cameo, the widely accessible narrative, through which racial and economic tensions are brilliantly woven, is far from passé.

Upon arriving at the middle-class family flat, Teresa (Angeli Bayani), a twenty-eight-year old Filipino domestic worker, hands over her passport to uneasy employers. Remaining silent, she is directed to a pathetic trundle bed in a room shared with a bratty nine-year-old boy. This could easily play out as a sob story about an overworked, helplessly timid, wholesome catholic immigrant, but such stereotypes of passivity are quickly pushed aside.

Jiale (Koh Jia Ler) welcomes “Auntie” by unsuccessfully attempting to frame her as a shoplifter, but Terry clarifies with startling dignity that she will not stand to be bullied. Though the veteran troublemaker carries on with the same insufferable attitude of defiance, he proves to be fiercely loyal as they gradually form an inseparable bond. Jiale is finally granted the attention denied by his double-income parents, but this alone does not explain the extraordinary depth of their affections.

The emasculated breadwinner Keng Teck Lim (Chen Tian Wen) has lost his sales executive job and rather than telling his wife or son, he humbly accepts a night watchmen temp position. He occasionally snaps at the henpecking from his wife, but the pregnant Hwee Leng (Yeo Yann Yann) is drained from full-time secretarial work and battling jealousy as Terry assumes a motherly role in her absence. Everyone in the household has difficulty communicating, so exhaustion and insecurity often crops up as contempt. At the same time, there is an unmissable warmth in small gestures of solidarity – like Keng Teck sharing his secret smoking habit with Terry or Hwee Leng pretending not to notice when she wears her lipstick. Rather than predictably peeling away a cold exterior to uncover human decency at the core, Anthony Chen delivers the ugliness of economic anxiety as it exists alongside genuine kindness. Suicide punctuates the familial troubles when Terry witnesses a stranger jump to his death.

Though devastatingly common during the Asian recession, Chen delivers an emotional punch lacking in nameless news stories. The stylized flood of white light and silence will leave you with an honest-to-god lump in your throat, while the desperate act serves as visceral reminder of a shared struggle. This collective suffering is precisely what lures a motivational speaker into town, as the dianetics-type con artist capitalizes on weakness. Hwee Leng hopelessly buys into the scam, while her son Jiale plays the lottery in a last-ditch attempt to save the nanny his family can no longer afford, but in the end, there proves to be no easy solution. Charged with all the sweetness and heartbreak of Ilo Ilo, Terry’s final advice to “learn to take care of yourself” nearly materializes into a lasting souvenir to be carried away from this Singaporean gem.