I Need a Lover with a Farmhand: Leopold’s Understated Portrait of Desire Deferred

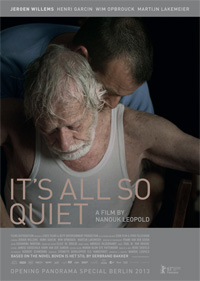

Loneliness and resentment are the dueling, omnipresent emotions on screen in virtually every frame in Nanouk Leopold’s It’s All So Quiet. Premiering back at the 2013 Berlin Film Festival, Leopold adapts from the novel The Twin by Gerbrand Bakker (who makes a small appearance in the film), and it seems to be aligned with a subject matter the Dutch filmmaker prizes—notions of secret desires. Those first being introduced to either Leopold’s work or that of the rather moving performance of its lead actor, Jeroen Williams, will be saddened to learn that he died suddenly at the end of 2012 at the age of 50, with this film’s dedication honoring his memory. It’s a reality that adds another layer to the film’s already sobering representation of lives caught in stilted familial histories.

Loneliness and resentment are the dueling, omnipresent emotions on screen in virtually every frame in Nanouk Leopold’s It’s All So Quiet. Premiering back at the 2013 Berlin Film Festival, Leopold adapts from the novel The Twin by Gerbrand Bakker (who makes a small appearance in the film), and it seems to be aligned with a subject matter the Dutch filmmaker prizes—notions of secret desires. Those first being introduced to either Leopold’s work or that of the rather moving performance of its lead actor, Jeroen Williams, will be saddened to learn that he died suddenly at the end of 2012 at the age of 50, with this film’s dedication honoring his memory. It’s a reality that adds another layer to the film’s already sobering representation of lives caught in stilted familial histories.

With his father’s (Henri Garcin) ailing health leaving him mostly bedridden, dutiful yet distant Helmer (Jeroen Williams) has taken over responsibility for the dairy farm, though he’s hardly enthused or emotionally invested in its success. There’s no warmth shared between the two as Helmer is forced to change his father’s soiled bedding or help him in the bath. But he’s a bit more expressive in his interactions with a dairy driver (Wim Opbrouck), who seems to ever so subtly flirt with Helmer, yet he fails to act on the possible advances. And here we begin to realize that Helmer’s been living a life of denial in more ways than one. In an attempt to make running the farm easier, Helmer hires a young farm hand (Martijn Lakemeier), though there’s immediately a sexual tension in their interactions that he isn’t able to necessarily hide or master.

Stillness is tantamount to Leopold’s mise en scene. We’re bookended by the corn field, at first empty, dry, barely rustled by the wind. Frank van den Eeden’s cinematography grazes almost apathetically over scenes of a farm environment that seems to be seeping into the ether before our very eyes, light often shrouded or dimmed as Helmer tends dutifully to animals and the responsibilities of the farm. It’s at first hard to decipher anything about father, son, or their relationship, other than that it’s strained. Other characters, such as the dairy driver, seem more curious as to why Helmer is struggling to keep things running, the dwindling animals inspiring him to inquire if this is a hobby. But the failing farm is meant to be a metaphor for father’s ailing health, both entities on their last gasp.

Superficially, It’s All So Quiet is very similar to the 2013 Swiss film Rosie (aka A Man, His Lover and His Mother), which finds a successful gay man return home to care for his ailing mother despite their strained relationship, leading him to an awkward liaison with a much younger man. But Leopold isn’t interested in melodrama or even dramatic tension, paring down the narrative drastically so that nearly every minute is entrenched in the inevitable death of Helmer’s father. It would seem suffocating if it weren’t for Williams’ restrained and often compelling performance, with a hooded, brooding gaze that belies a weary suffering. Stripping naked while alone at night, we sense that there’s a deeply misunderstood desire within him, something immediately apparent in his stares at farmhand Henk. So repressed is Helmer, he rebuffs all contact (including the shy advances of the dairy driver) until Henk makes a more aggressive attempt to connect with Helmer, resulting in the film’s only real scene of shared human warmth or comfort.

Very late in the film we learn minor details that hint at the disastrous fissure between father and son, which has something to do with Helmer’s dead brother. “Why do you dislike me so?” queries the father in one of their rare discussions about elements other than farming. Helmer doesn’t answer because words cannot convey correctly such contempt born out of years of disappointment, rejection, and lack of acceptance. Instead we get Williams’ tiredly withered gaze.

★★★/☆☆☆☆☆