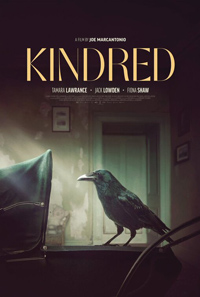

Gaslight of My Life: Marcantonio Debuts a Familiar Slice of Maternal Psychodrama

“She giveth life and take it away” could have been a fitting tagline for Kindred, the directorial debut of Joe Marcantonio, a familiar and somewhat archaic psychodrama which depends a bit too conveniently on assumed gender stereotypes and genre tropes. Still, the narrative’s insistent claustrophobia manages to frustrate expectations and allows for a trio of performances which become increasingly more uncomfortable as we learn more about past traumas which really churn the film into a display of developmental issues and the dysfunctional attachment styles they instill.

“She giveth life and take it away” could have been a fitting tagline for Kindred, the directorial debut of Joe Marcantonio, a familiar and somewhat archaic psychodrama which depends a bit too conveniently on assumed gender stereotypes and genre tropes. Still, the narrative’s insistent claustrophobia manages to frustrate expectations and allows for a trio of performances which become increasingly more uncomfortable as we learn more about past traumas which really churn the film into a display of developmental issues and the dysfunctional attachment styles they instill.

Though it may have worked better as a period piece, subtexts regarding class and race are unwisely kept at bay, which is a pity considering the potency of lead Tamara Lawrance in her battle of wills against a manipulative, and equally showcased performance from the underrated Fiona Shaw.

Ben (Edward Holcroft) and Charlotte (Lawrance) are a happily devoted couple just shy of two years into a committed relationship. Circumstances have allowed them to live happily adjacent to the estate of Ben’s imperious mother Margaret (Fiona Shaw), who resides in a crumbling but palatial home in rural Scotland alongside his stepbrother Thomas (Jack Lowden). Strangely, Thomas seems more of a servant, and Ben is somewhat contemptuous towards him. When Charlotte and Ben announce they are moving to Australia, Margaret is none too pleased. Shortly after, Charlotte reveals she’s pregnant, and she begins to have strange visions of crows and magpies, a bad omen. A tragedy on the estate claims Ben’s life, leaving Charlotte all alone. Diagnosed by a cool, clinical physician (Anton Lesser) as needing bed rest, Charlotte finds herself locked inside without a phone or a car.

Gaslighting narratives depend on a few immovable features, usually requiring the establishment of complex cultural or unique vulnerabilities for the (generally female) protagonist. Marcantonio and Jason McColgan’s script tends to gloss over some of the parameters which make this seem logical for Charlotte’s character. Vague insinuations on her own mother’s compromised mental health notwithstanding, a broken smart phone and rural isolation aren’t ultimately strong enough factors to explain why she doesn’t simply abscond during several key opportunities.

True, she has no resources and her other outlets prove to be futile (the treachery of her only friend, played by Chloe Pirrie, is also nonsensical), while vague motifs about a sinister magpie try to establish a girding supernatural element. But these all feel like a narrative grasping at straws to keep the wheels rolling, because Kindred never bothers to at least mention the resiliency of Black women who have learned they cannot depend on the white power structure, so Charlotte remaining in captivity only because there’s nowhere else to go feels like a sham.

Of course, Kindred cannot help but remind one of a plethora of similar narratives of pregnant women in peril. Aping some of the artifice of Rosemary’s Baby (1968), it also bears shades of the Tallulah Bankhead-Stefanie Powers camp classic Die! Die! My Darling (1965), and the much later (and hopelessly woebegone) Hush (1998) with Jessica Lange and Gwyneth Paltrow. Notions of motherhood and lineage abound, and kudos to Shaw as Margaret for a continual vehemence which is born from a mania for control rather than anything else.

One wishes, however, for a bit more complex psychological cat-and-mouse antics, perhaps something which reached for such maternally concerned potentials, like Olivier Masset-Depasse’s 2018 Mother’s Instinct (currently set for an English language remake). If only Kindred wasn’t intent on eschewing all its sinister ambiguities, nixing any kind of thought the tragedy of Ben could have been intentional, and allowing a monologue for Lowden’s Thomas which explains the trauma which has brought him into the clutches of Margaret but for naught – rather, he’s just a piano-playing quiche maker whose has found a comfortable niche as the shadow of Margaret’s son. Perhaps if we had some better idea of Margaret and Thomas’ scheming, Kindred’s finale would seem more sinister. As it stands, it’s merely a reminder of how little control women ultimately have over their body sans a support network and when they aren’t advocating for themselves.

★★★/☆☆☆☆☆