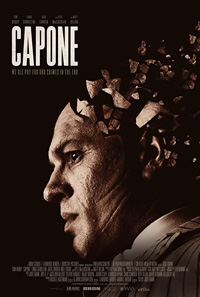

Gonzo Fonzo: Trank Returns with Tone Poem Portrait of a Monster

The figure of Chicago mobster Al Capone has long been a mythical figure resurrected time and again on screen, played by a variety of notables, including Rod Steiger, Jason Robards, Robert De Niro and several others. Usually, the tendency is to showcase the man in his prime, or at least include either the infamous St. Valentine’s Day Massacre or his highly publicized trial for tax evasion, which saw him serve nearly a decade in prison, wherein syphilis would erode most of his mental capacity.

The figure of Chicago mobster Al Capone has long been a mythical figure resurrected time and again on screen, played by a variety of notables, including Rod Steiger, Jason Robards, Robert De Niro and several others. Usually, the tendency is to showcase the man in his prime, or at least include either the infamous St. Valentine’s Day Massacre or his highly publicized trial for tax evasion, which saw him serve nearly a decade in prison, wherein syphilis would erode most of his mental capacity.

Director Josh Trank, returning from the formidable failure of 2015’s Fantastic Four, gets a chance at unleashing a new perspective on one of history’s most infamous criminals in this reimagining of the man’s last year of life as he wasted away in Florida. An extreme ‘method’ performance from Tom Hardy will either be cause for ridicule or reluctant praise as a mumbling murderer haunted by the ghosts of his violent past.

After serving nearly ten years in prison for tax evasion, notorious Prohibition era Chicago gangster Al Capone (Hardy), aka Fonzo, is released to live out the rest of his life in Florida while being watched by the FBI. It seems he had pilfered away ten million dollars prior to serving his sentence—if only he could remember where he put it. Suffering from neurosyphilis, the severely mentally debilitated Fonzo lives in a waking nightmare, unable to tell hallucination from reality. Neither his old mentor Jimmy (Matt Dillon), his wife Mae (Linda Cardellini) or a physician with ties to the FBI (Kyle MacLachlen) are able to glean any useful information from him, while his anguished episodes become more and more violent.

Considering Trank’s last two features were superhero related, including his 2012 debut Chronicle and the ill-fated 2015 reboot of Fantastic Four, his tackling of Capone’s (previously titled Fonzo) final year seems a novel departure. However, it’s unclear what the take away should be. It seems Capone means to take pains to showcase there was more to the infamous gangster than the general mythos seems to acknowledge, but there’s little empathy to be gleaned for the man whose regrets seem born out of his subconscious dismantling due to the neurosyphilis eating away at his brain.

The end result plays like a superficial Scorsese film, recalling the autumnal regrets of The Irishman and borrowing the violence of Casino (a gory stabbing sequence plays like a choice sequence of Joe Pesci using a pen from that 1995 Scorsese epic). Compared to a number of previous portrayals of Capone, Hardy’s take plays like his Bronson (2008) by way of the Batman villain Bane, a reptilian voiced monster thrashing out from the depths of his own nightmare.

Hardy’s affect takes some getting used to, and perhaps if the rest of Capone had matched this weirdness instead of juxtaposing it Trank’s film would feel a bit more cohesive. For those unaware of Capone, this is hardly the starting point, either as a key figure of mobster lore or a representation of the ravages of syphilis (perhaps some mention of the medical treatments of the period would have helped some of the questions requiring a bit of additional research).

Certain period sequences are used for convenience to underline the period’s affect, such as Louis Armstrong singing “Blueberry Hill,” when this particular recording didn’t happen until after Capone’s death. His love for Puccini, also highlighted in De Palma’s The Untouchables (1987), is used as an aural refrain here, but again, more as a loose fragment than anything insightful. But as a low-key portrayal of a particularly contained period, Capone benefits from a formidable musical score from El-P (who also worked with Trank on Fantastic Four) plus David Lynch cinematographer Peter Deming (who lensed both the 2017 remount of “Twin Peaks” and Mulholland Drive).

Kyle MacLachlen and Matt Dillon are welcome figments, if a tad underutilized, as is Linda Cardellini, once again playing the shadow of an omnipotent husband as she did in films starring Mark Wahlberg (Daddy’s Home, 2015) and Viggo Mortenson (Green Book, 2018). Ultimately, Capone plays like a showcase for Hardy, but what it’s saying about consequences and regrets for one of the twentieth century’s most violent historical figures is unclear.

★★★/☆☆☆☆☆