Looking Back Instead of Forward: A New Kind of Coming-of-Age Tale for Linklater

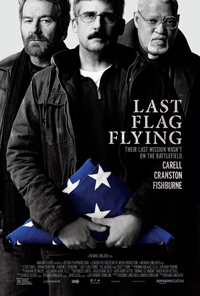

Rare is the filmmaker who can entertain with little more than old-fashioned conversation – but Richard Linklater is one of the few. His latest feature, Last Flag Flying, is an understated, surprisingly hilarious anti-war film … with a whole lot of talk. Like so many Linklater movies, it’s about coming-of-age; the difference is that this one looks back instead of forward. The tone is set early on when weathered alcoholic Sal (Bryan Cranston) growls, “We were all something once. Now we’re just something else.” Last Flag Flying is a film where duty meets conscience; it’s also one of the year’s most poignant laugh fests.

Rare is the filmmaker who can entertain with little more than old-fashioned conversation – but Richard Linklater is one of the few. His latest feature, Last Flag Flying, is an understated, surprisingly hilarious anti-war film … with a whole lot of talk. Like so many Linklater movies, it’s about coming-of-age; the difference is that this one looks back instead of forward. The tone is set early on when weathered alcoholic Sal (Bryan Cranston) growls, “We were all something once. Now we’re just something else.” Last Flag Flying is a film where duty meets conscience; it’s also one of the year’s most poignant laugh fests.

Based on a book of the same name by Darryl Ponicsan – a sequel to Ponicsan’s The Last Detail (directed by Hal Ashby in 1973) – Last Flag Flying echoes Ashby’s intimate character study, laced with layers of Linklater ideology. The script was co-written by Linklater and Ponicsan. Set in 2003, it follows three aging Vietnam vets on a physical and emotional ride, after one of their sons is KIA in a Baghdad ambush. The former wartime buddies find out that this isn’t the full story; they decide to take matters into their own hands. The result is a meandering road trip filled with SNAFU’s – plus a soul-searching mix of nostalgia, patriotism, pride, regret, and the power of truth-telling. Ultimately, the cover-up takes a back seat to more intimate conflicts. The film’s performances all hit home.

Steve Carrell plays Larry ‘Doc’ Shepherd, a former Navy doctor who did brig-time for helping his buddies get their hands on morphine. Back then, Doc was a victim of peer pressure; now he’s a victim of the institution that he used to serve. His wife and son are both dead, so he looks to his wartime companions for solace and closure. Carrell’s performance is spare, almost brooding: not unlike his character from Little Miss Sunshine (another road movie, no less). His few moments of humor are effective, in part thanks to their rarity.

Bryan Cranston, as the grizzled Sal, owns the film. A high-energy cynic, he plays the most ‘typically Linklater’ character: the not-quite-grown up war lifer, who can’t move on from the Marines any more than Matthew McConaughey’s Wooderson (Dazed and Confused) could move on from high school. He’s also reminiscent of Nicholson’s character Billy “Badass” Buddusky (The Last Detail) – with his own brand of old-man bluster. He owns a bar, sleeps in it, and brings it with him wherever he goes. He’s a shit-talking champ full of irreverent jokes, holding court with drunks too sedated to care what he’s saying. Underneath, he’s profoundly lonely.

The yin to Cranston’s yang is Laurence Fishburne. He plays Richard ‘The Mauler’ Mueller, a once wild soldier now reformed and refined into a Reverend. At first, he plays the straight man, earning his keep with reserved retorts and measured silences; then he starts jousting with Cranston. Their belief systems clash, they bicker and badmouth – but beneath the surface lies a fierce friendship. Their interactions and energy drive the film.

Also worthy of note are Cecily Tyson in a too short-but-spirited turn as Mueller’s wife, and J. Quinton Johnson as the young blood Marine known as ‘Washington.’ Johnson – who debuted as the cocksure Dale in Linklater’s Everybody Wants Some!! – is remarkably moving: as best friend to Doc’s deceased son, his character allows lonely Sal a chance to play ‘dad.’

Together, the ensemble shines – especially because they deliver those casually philosophical insights that Linklater films are so known for. Yes, the dearth of female characters is notable, but hardly surprising given the film’s context … plus Linklater’s history of unapologetically male-driven films. In this film, it’s manhood that matters. Unlike many Linklater males, these characters are older – but their essence hasn’t changed. With Vietnam behind them and Iraq as a painful reminder, this, too, is a bildungsroman – with a sizeable dose of nostalgia. Despite years out-of- touch, these three vets swiftly revert to their wartime dynamics. A long-lost nickname, a jibe… It doesn’t take much to bring their memories – and emotions – to light.

Last Flag Flying is tragic, but in no way maudlin. The dialogue never feels cheap or watery; it doesn’t waste time on melodrama. Instead, it jumps straight into reaction – ‘How the fuck am I going to deal with this?’ – and survives a two-hour length without feeling tedious. It’s also nothing short of hilarious. The film’s humor elicits more deep emotion than any of its dramatic moments or silences. One of its most resonant scenes revolves around dick jokes: proof of how we use laughter to cope with grief.

Visually, this film is remarkably un-stylized. The plot unfolds in close, confined quarters: cars, bars, trains. The camera focuses almost entirely on faces. Even Linklater’s normally buoyant camera remains largely stationery. But it feels right: the story’s gravitas needs naturalism. The lack of artifice means that when the camera finally circles a car, or begins to push in, you notice. The intensity heightens.

Most absent from the film is music. Linklater’s period-specific scores that have served so well in past films are replaced by a forgettable undertone. In one scene, Cranston and Fishburne debate an Eminem song and their distaste for hip hop. It’s a highlight, but just scratches the surface. Linklater fans may feel that his signature musical ear is missing.

Last Flag’s biggest problem? The film feels too safe. For a filmmaker so revered for playing with form – from an improvised trilogy to a 12-year saga to a frat-bro nostalgia-fest – this latest work feels too written. Too faithfully adapted. It begs for a little more of the director’s DNA; one wonders what it might have been with a little more creative abandon.

But even without the music, even without Linklater’s signature risk-taking, Last Flag Flying is a fitting addition to his body of work. It’s a tender, well-told story, ripe with finger-on-the-pulse humor. Like his Dazed and Confused, it gives us an uproarious slice-of- life; like his Before trilogy, it explores the inexorable flow of time and shared understanding.

It’s also supremely relevant, a cautionary tale for our country. It has moments of genius, with tonal shifts that echo Joseph Heller, or the recent war satire Foxtrot. It poses critical questions: Do we ever come of age in America? Do we require crisis to recognize deeper truth? Can the lessons we learn be passed on to the next generation? Those are Linklater touches. But Last Flag Flying is not satire, it’s not message-driven, and that’s where this film shines. It confronts war without being confrontational. It’s a deeply human story, presented as if we’re the only one in the room.

Reviewed on September 29th at the 2017 New York Film Festival – Opening Night Selection. 124 Mins.

★★★★/☆☆☆☆☆