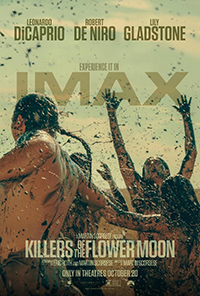

The Moon in the Gutter: Scorsese Tackles the Osage Nation Murders

Martin Scorsese’s highly anticipated adaption of David Grann’s 2017 non-fiction publication Killers of the Flower Moon is rearranged to reflect the perspective of two masterminds behind a shocking genocide of the wealthy Osage Nation in the 1920s. It was a widespread means of greedy, devious white men attempting to usurp control of Osage headrights to the oil rich Oklahoman soil they own. While Grann’s account provides a much more comprehensive overview, the Osage were forced into what was considered generally undesirable territory, only to find themselves sitting atop a bounty of black gold, which would make them far wealthier than their endlessly resentful white counterparts. A cue card explains they were the wealthiest people per capita in the 1920s. After a decade of killing, two of the main perpetrators were held accountable following a highly publicized trial. But what Grann’s expose details (and Scorsese’s adaptation does not) are the countless unsolved murders of the Osage not directly related to those apprehended for the murder of nearly all of Mollie Kyle Cobb’s family. A rather straightforward but routinely exceptionally produced true crime saga from Scorsese, there’s a sense of the narrative going through the motions while circumventing the complex Bureau of Investigations manhunt for the perpetrators.

Martin Scorsese’s highly anticipated adaption of David Grann’s 2017 non-fiction publication Killers of the Flower Moon is rearranged to reflect the perspective of two masterminds behind a shocking genocide of the wealthy Osage Nation in the 1920s. It was a widespread means of greedy, devious white men attempting to usurp control of Osage headrights to the oil rich Oklahoman soil they own. While Grann’s account provides a much more comprehensive overview, the Osage were forced into what was considered generally undesirable territory, only to find themselves sitting atop a bounty of black gold, which would make them far wealthier than their endlessly resentful white counterparts. A cue card explains they were the wealthiest people per capita in the 1920s. After a decade of killing, two of the main perpetrators were held accountable following a highly publicized trial. But what Grann’s expose details (and Scorsese’s adaptation does not) are the countless unsolved murders of the Osage not directly related to those apprehended for the murder of nearly all of Mollie Kyle Cobb’s family. A rather straightforward but routinely exceptionally produced true crime saga from Scorsese, there’s a sense of the narrative going through the motions while circumventing the complex Bureau of Investigations manhunt for the perpetrators.

In 1920s Osage County, Oklahoma, a series of unsolved murders amongst the Osage Nation suggested there was a grand plan to eradicate all members of the tribe who had headrights, the legal control of the oil rich lands they lived upon. Prior to many of the killings, there were other devious attempts to control them, as many tribe members were declared legally incompetent, requiring they have a white guardian to monitor their funds. Suspicious ‘accidental’ deaths began to plague them, including via poisoned alcohol, mysterious ‘wasting’ diseases, and an alarming amount of ‘suicides.’ Arriving in this milieu is Edward Burkhart (Leonardo DiCaprio), something of a naive innocent who has been invited to work for his wealthy uncle, William Hale (Robert De Niro), a man who’s wiggled his way into the good graces of the tribe. Burkhart woos Mollie Kyle Cobb (Lily Gladstone), and they soon marry, having children. But her condition as a diabetic begins to flare up, limiting her. Shortly after their marriage, her sister Anna is found murdered right after another tribe member is shot and killed in a similar manner. Another sister suffers from wasting disease, whose husband then weds her last remaining sister Reta. Both of them are blown up by explosives placed beneath their home. Despite the hiring of a private investigator who promptly disappears, and a local townsperson tasked with going to Washington, D.C. to request help solve the murders, it seems the Osage are on the verge of extermination until a federal law enforcement agent, Tom White (Jesse Plemons) arrives with an undercover team.

Reuniting with two of his most beloved collaborators, Scorsese gives Leonardo DiCaprio and Robert De Niro carte blanche in detailing this heinous affair. The final result is purportedly due to DiCaprio wanting to play Ernest Burkhart rather than lead agent Tom White, and Killers of the Flower Moon plays through his somewhat circumspect involvement suggesting, quite frustratingly, he was as much a victim of circumstance as anyone else. Still, outfitted with crooked teeth and the kind of downturned maw Marlon Brando might have utilized, DiCaprio manages to make this passive dummy of a man into an utterly watchable creature. However, it’s Robert De Niro as the maliciously Machiavellian maestro pulling all the strings who really steals the film, even if this sometimes allows for a dark comedic energy to pull away from the significant betrayal and horrendous violence he fostered against the Osage. The composed and regal Lily Gladstone succeeds in making Mollie sympathetic and despairing in her obliviousness to the snake beneath the asp. One wonders how this might have felt more of an alarming film had it been told from her perspective.

Scorsese unveils the narrative in mostly chronological order, a brief prologue setting us up for the arrival of Burkhart, an aimless veteran, to work for his well regarded uncle. Immediately, Hale plants the seeds for his ‘good business’ plan into his nephew’s simple brain, vocalizing it would behoove him to marry a full-blooded Osage woman to gain access to her wealth. This turns out to be step one in Hale’s plan to annihilate all her surviving family members so she inherits everything before killing her and, as his thought process seems to go, Burkhart as well. He’s waylaid thanks to the intervention of Tom White, dispatched by J. Edgar Hoover, when the FBI was still known as the Bureau of Investigations, an agency still trying to prove its merits. Scorsese documents several reasons why investigations were stymied and delayed, allowing for nearly a decade worth of murders to transpire before a modicum of justice was served. But despite several violent spectacles, there’s something of a detachment from the brutality which customarily defines Scorsese’s gangland epics, as well as a diminishment of white America’s extreme racist tendencies. These ignorant attitudes are attenuated, but Killers of the Flower Moon doesn’t convey the ugly extent to which they permeated the culture to such a degree it’s a surprise actual convictions were brought against Hale and Burkhart at all. This partially seems due to the film wanting to retain a certain level of ambiguity about Burkhart, depicted here as someone who actually believed he loved his wife, even though he was poisoning her insulin and assisting in the murder of her family.

Utilizing his regular collaborators DP Rodrigo Prieto, composer Robbie Robertson, and editor Thelma Schoonmaker, Killers of the Flower Moon is certainly a handsome affair (as De Niro tells DiCaprio, “you have a nice face”), but there’s a certain energy missing, an element needed to really drive home the darkness.

Reviewed on May 20th at the 2023 Cannes Film Festival – Out of Competition. 206 Mins

★★★/☆☆☆☆☆