Such Great Heights: Covino & Marvin Mine the Nexus of Toxic Friendships

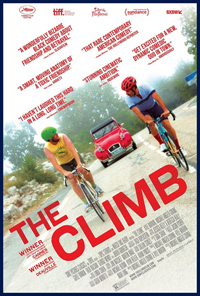

Friendships between heterosexual men are already an anomaly in cinema, and representations are often filtered through their romantic relationships with women, as halting and stifled as the rigid masculinity which defines these counterparts. Director Michael Angelo Covino and his co-star and co-writer Kyle Marvin, each playing characters of the same name, grapple with a presentation a bit more complex in The Climb, which debuted at Cannes in 2019 and is based on their 2018 short film.

Friendships between heterosexual men are already an anomaly in cinema, and representations are often filtered through their romantic relationships with women, as halting and stifled as the rigid masculinity which defines these counterparts. Director Michael Angelo Covino and his co-star and co-writer Kyle Marvin, each playing characters of the same name, grapple with a presentation a bit more complex in The Climb, which debuted at Cannes in 2019 and is based on their 2018 short film.

Bearing a multitude of homages to French cinematic themes, it’s an example of amour fou for the painstaking platonic realm, hinging on farce before sprawling awkwardly spreadeagle into the kind of poignancy as authentic as it is rare in explorations of human relationships. Frustrating but ultimately rewarding, it’s a cinematographic marvel which runs with feverish intensity into a passive aggressive ellipsis of thoughts and themes.

Kyle (Kyle Marvin) is about to marry Ava (Judith Godreche), the woman he believes is ‘the one.’ On an uphill bike ride in France, his long-time best bud Mike (Covino) confesses he’s been sleeping with Ava on and off throughout their courtship over the past three years. An altercation with a Frenchman due to Mike’s needling leads them to the hospital, where it is confirmed his impending marriage to Ava is now over. Fast forward some time to the next sequence at Ava’s funeral, with a eulogy from the devastated Mike. More time passes, and while at a fraught Thanksgiving at Kyle’s family house, where his engagement to an old high school flame, Marissa (Gayle Rankin) sows discord, Mike shows up, invited by Kyle’s mom. Hopelessly inebriated, it’s his opportunity to wheedle his way back into Kyle’s good graces, but he immediately sets out to drive Marissa and Kyle apart.

What goes up must come down, or so seems to be the case for Mike and Kyle, apparently eternally tethered thanks to their high school friendship which saw the former absorbed by the latter’s family. The opening two sequences, which feature Judith Godreche (a standout in Patrick Brice’s The Overnight, 2015) as the initial conquest stolen by Mike, sets up a scenario mapped out frequently by the likes of Jean-Claude Carriere. At one point, Mike ends up at a local French Film Festival where Le Grand Amour (1969) is screening, written by Carriere, while Covino’s own scenario is similar to another Carriere script, 2018’s A Faithful Man, directed by Louis Garrel.

Covino sometimes descends into an overly mannered idiosyncrasy, dividing the film into seven chapters, including three magical realism segues of singing grave diggers, syncopated skiing, and a musical aside which sometimes err on the side of tweeness. The more powerful transitions occur, both visually and tonally, through Zach Kuperstein’s (The Eyes of My Mother, 2016) cinematography. Continuous shots comprised of long, sinewy takes, such as one beautiful showstopper at the Thanksgiving celebration at Kyle’s, moves like a ghostly specter into the dusk, rooting out Mike at the end of a long line of cars in the driveway, downing a bottle of booze.

Stuck between them is the feisty Marissa (a bewitching Gayle Rankin), with Kyle’s family (including parents played by Talia Balsam & George Wendt) so opposed to their romance it basically thrusts them together. Mike’s continual sabotage, born out of his own apparent self-loathing and lack of emotional support outside Kyle and his family, recalls something like those eternal frenemies played by Meryl Streep and Goldie Hawn in Death Becomes Her (1992), one always stealing the lovers of the other, both as a way to win an unstated competition and as well as fill a bottomless black hole of self-doubt.

This culminates in the film’s climax, a sort of reversal on the wedding scene from The Graduate (1967), where, for the first and only time, a dubious but poignant exchange of desperate vows occurs between Kyle and Marissa. Ending where it more or less began, a reflection of the film finding its own particular cadence, The Climb might take some settling into, but it’s a strange odyssey of complex relationships born from necessity and circumstance, landing on a curiously offbeat note which seems to celebrate connections between people despite their sometimes formidable imperfections.

★★★½/☆☆☆☆☆