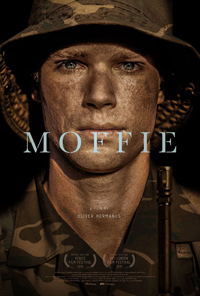

Call Me by Your Shame: Hermanus Mines Historical Trauma in Coming-of-Age Drama

It’s difficult to reconcile the messiness of the past with potential issues of accountability for those who straddle a precarious line between victim and victimizer. As such, there’s more to parse than meets the eye in Moffie, the fourth feature from South African auteur Oliver Hermanus.

It’s difficult to reconcile the messiness of the past with potential issues of accountability for those who straddle a precarious line between victim and victimizer. As such, there’s more to parse than meets the eye in Moffie, the fourth feature from South African auteur Oliver Hermanus.

Based on a novel by Andre Carl van der Merwe, thus named for the Afrikaans slur for gay men (the English-derived epithet which served as a title for Larry Kramer’s 1978 novel as well), Hermanus concocts the anti-Call Me by Your Name sentiment, or rather, a more commonplace tale where coming-of-age for young gay men is besotted by trauma and self-loathing.

Hermanus takes us back to early eighties South Africa, where the racist apartheid era was staunchly defended and children sixteen years and above were conscripted to serve in a conflict with bordering Angola. Fearing the Communist attitudes of their neighbors and wishing to uphold with white, racist power structure (apartheid didn’t end until 1994), the literal conflict is mirrored internally through the muted sexual awakening of a half-Brit, half-South African young man who seemingly compartmentalizes his grief, his desire, and his integrity.

1981 South Africa. Nicholas van der Swart (Kai Luke Brummer) begins his two-year conscription in military service (despite holding a British passport thanks to his lineage, which technically means he could have applied for an exemption). The country is involved in conflict with bordering Angola, whose Communist views and anti-apartheid sentiments are at odds with the racist, white minority governing South Africa. Nicholas is also hiding his homosexuality, which makes his two-year service all the more harrowing in the brutally racist, homophobic environment. During training, two colleagues are caught in a homosexual act and sent to the dreaded Ward 22. But his anxieties are momentarily quelled by a quiet but reciprocal romance with Stassen (Ryan de Villiers). Upon returning from break, it appears Stassen’s sexuality has been discovered while Nicholas struggles in vain to discover the fate of his doomed love interest.

While Brummer is fetching as a screen presence (resembling the Swayze’s), Hermanus seems more interested in showing how a collection of notable experiences have brought Nicholas to a precipice, ostensibly wiping his slate clean as he decides who he wants to be. Not shying away from the trenchant racism of South Africa, Nicholas appears afraid to speak his mind, observing the terror inflicted by his fellow soldiers, and in one of the film’s more subtly moving sequences, watches the life ebb out of a Black Angolan soldier he’s shot.

As with his 2011 masterwork Beauty, Hermanus feels most concise when dealing with problematic developments of repressed desire in gay men and their resulting ripple effects. One of the most striking sequences is a flashback to an early trauma for Nicholas at a community swimming pool, a segue which fits significantly into the formulation of Stassen’s denouement.

It’s easier to feel more empathetic about the trenchant homophobia Nicholas is forced to navigate than his involvement as an (arguably captive) accomplice to South Africa’s racist military machine. And strangely, Moffie must contend with presenting queer victims who are also part of the problem (not unlike films dealing with gay Nazis or gay Republicans, affiliations where whiteness or nationalism provide safety but cost one’s integrity).

Shot by Jamie Ramsay (who lensed Beauty and the upcoming Eva Husson film), Moffie is a beautifully attenuated arthouse film, collapsing classic musical pieces atop emotional and physical traumas. Hermanus creates a variety of metaphorical visuals, such as the moving finale, where Nicholas and Stassen gaze warily at one another as the longing gestures of their submerged limbs suggest a need they’re unable to vocalize—nothing is ever what it appears on the surface. As such, Hermanus’ latest is reminiscent of early Verhoeven titles dealing quite bluntly with queerness and societal mores, such as The 4th Man (1983) or Spetters (1980).

★★★½/☆☆☆☆☆