January Man: Schrader Fans the Underbelly in Morose Facade of Lost Souls

Paul Schrader has obsessively charted the propensity of man’s repressed compulsions consuming even the most well-balanced of his dysfunctional protagonists. Whether its been mental illness, demons, pornography, prostitution, supernatural shapeshifting, religion, thwarted desires, or addiction, his is a worldview of humans hanging on by a thread, the only difference between many of them being whether they’re descending into the pit or clawing their way out of one.

Paul Schrader has obsessively charted the propensity of man’s repressed compulsions consuming even the most well-balanced of his dysfunctional protagonists. Whether its been mental illness, demons, pornography, prostitution, supernatural shapeshifting, religion, thwarted desires, or addiction, his is a worldview of humans hanging on by a thread, the only difference between many of them being whether they’re descending into the pit or clawing their way out of one.

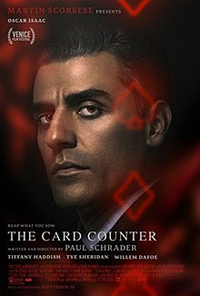

Following a return to critical acclaim with 2017’s First Reformed (read review) the resulting creative control suggests a surging renaissance with his latest, The Card Counter. It’s an oxymoronic thrill with his resumption in the same vein of wounded masculinities which marked many of his perversely oriented early works, though perhaps mostly for the most sadomasochistic among us. Simultaneously, it’s an often frustrating switch-hitting melodrama defying expectations of both morality or obvious entertainment. This is a muted world of grief-stricken adults trying valiantly to keep their head above the stagnant, oppressive waters of the past. As such, Schrader’s power lies in the small poignancies and passing kindnesses between those who recognize themselves in the haunted anguish of those around them.

Recently released from an eight-and-a-half-year stint in Leavenworth due to his actions in service at the infamous Abu Ghraib, William Tell (Oscar Isaac) languishes away as a card counter who lives off “modest” winnings to float between card tournaments throughout the midwest. A chance run-in with La Linda (Tiffany Haddish), who played with Tell in the past and now runs her own stable, offers to broker him backers for bigger winnings. Opposed to ‘celebrity gambling,’ he initially declines the offer. But another chance meeting with Cirk (Tye Sheridan), who has ties to Tell’s troubled past, finds him inviting the lost young drifter to be his traveling companion. As a means to an end, he takes La Linda’s offer, agreeing to run the circuit for a year and establish a nest egg allowing him to live comfortably before he finally walks away from this chapter of his life. La Linda potentially has other interests, but Tell’s past won’t allow him to reciprocate. Cirk’s insidious plans to torture those who wronged his father eventually force Tell’s hand.

Schrader is at his perhaps most Dostoevskian here, with Isaac’s William Tell like Raskolnikov post the Siberian prison camp experiences of The House of the Dead, mixed in with some bits of levity and humor which never feel homogenous, as ill paired as the pastor’s choice drink mixes in First Reformed. A grating, overly repetitive harangue is a patriotic card player also making the rounds of the tournament, an entourage of bros chanting “USA” whenever he wins (which is often), and makes the film feel more like an Altman film, befitting of California Split (1974).

“Is there an end to punishment?” he writes to himself in nightly journal entries which flow with the help of brown liquor. His character tic is holing up in rundown motels rather than enjoying the more opulent climes of the casinos he frequents, obsessively covering up the entire room with white sheets, re-creating the internal emotional tomb of his shame and guilt. He lives like a man intent on passing time until he can peacefully expire, and thus the mechanical rigidity of his titular ‘skill’ operating as a mere coping mechanism.

Masquerading as a heist film, it becomes clear the crossroads William faces pull him simultaneously to his past and the promise of a future—but he can’t look both ways at once. The film’s enigmatic tendencies are finally explained with his chance meeting of Cirk (pronounced “Kirk”), both spying on a presentation given by Dafoe’s John Gordo, a mustachioed orator running through a rather rote slideshow on new technological advances wherein facial recognition algorithms could take the place of those pesky lie detector detests which hobble new hires in law enforcement agencies. Eventually, this sermon is revealed as ironic considering it was Gordo’s absent face which allowed him to escape sanction in the aftermath of Abu Ghraib. As Circk, Sheridan is a rather petulant moper, having concocted a dark death wish to avenge his broken childhood at the hands of a father who suffered a similar fate to Tell. In him, William sees a chance at either revenge or redemption, ultimately choosing the latter. Unfortunately, fate has a way of shoving us violently towards other reckonings.

It’s a curious character piece, conjuring an empathy for a man whose actions in the line of duty were incontrovertibly unforgivable. Schrader’s screenplay marries metaphors of gambling and impulses, like ‘force drift’ and ‘tilt.’ He likes ‘dependable’ and ‘anonymous’ endeavors in his sustainable hobby, which is why he resists the obvious advances of Haddish’s La Linda. Although it’s an inspired bit of casting, Haddish is often reduced to mugging in a handful of scenes where she’s watching a game passively or ordering various drinks with William and/or Cirk between rounds. She adds an odd accent, and although not wholly unlikeable, it’s as if her vibrancy is a constant reminder of a more intriguing, healthier world outside the jangling slot machines and windowless conference rooms.

Sheridan and Isaac eventually earn a semblance of a hard-won camaraderie, but Isaac’s internalized self-loathing often makes him seem like the functional version of Travis Bickle (arguably underlined by Schrader’s original cohort Martin Scorsese on board as one of the project’s producers)—his darkness may lie dormant, but he’s so closed off from the world it’s difficult to see how his two new cohorts segue so quickly into intimates. Dafoe (and a briefly glimpsed Dan Hedaya) are jaundiced monsters in the fisheye lensed flashbacks to the torture chambers, and rightfully infect the present day sequences. While doom seems inevitable, Schrader ends on a note which channels the finale of his 1980 classic American Gigolo, the tenuous possibility of hope through tenderness.

Reviewed on September 2nd at the 2021 Venice Film Festival – Main Competition. 112 Mins.

★★★/☆☆☆☆☆