Waiting For Tonight: Goded Finds Friends in Circle of Sex Workers

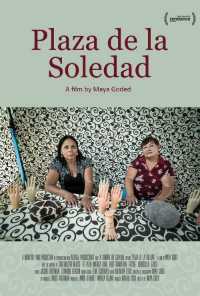

Having spent the last 20 years visiting Mexico and the notoriously dangerous streets of the La Merced district in search of raw and revealing still images, the renowned photographer Maya Goded has developed a close connection with the tight-knit community of miraculous women who’ve made a lifelong career of prostitution, despite the risks and emotional tumult inherent to the job. Much like the book of Goded’s photos published under the same title back in 2006, Plaza de la Soledad, which translates as Loneliness Square, the photographer-turned-filmmaker’s first foray into the documentary feature form reveals an intense, and ultimately moving sense of trust between her and her subjects, while painting a portrait of modern Mexico less haunted by drug cartel than survived by average people just struggling to find some semblance of happiness.

With an endearing sense of reverence, we’re introduced to Carmen, Lety, Raquel, and Esther, a clique of lifelong streetwalkers all over the hill who converse with one another as friends, and when alone, occasionally address the camera. As hardened veterans of the night, they’ve thoroughly mastered their craft and harbor absolutely no humiliation about how they pay the bills. In the presence of Goded and her camera, these women are seen working the same plaza they’ve worked for years, and remarkably, they seem to be wholly accepted by their community. Each of them seems to know each shop keeper and street stand serviceman, graciously greeting them on the way to their usual haunt, at which the camera doesn’t even seem to disturb eager customers.

This type of work is not only dangerous, as we’ve seen most recently in Kim Longinotto’s Dreamcatcher and Nick Broomfield’s Tales of the Grim Sleeper, but profoundly catastrophic for one’s emotional well being. Surprisingly, the world depicted here seems far less scary than that of Longinotto or Broomfield’s – rather than nightmare scenarios, dreams of falling in love still lingers in the back on these women’s minds and Goded spends the majority of the film highlighting the warm relationships these women have with one another, as they possess a unique understanding of one another’s situations. That said, they admit they’ve developed callused hearts that have become necessarily numb to hope. What physical pleasure that might still be able to be gleaned from random or regular sexual encounters is fleeting at best, and thus they’ve learned to rely on their sisters in prostitution for emotional support and physical tenderness. And they deeply need it.

Women don’t grow up hoping to be prostitutes when they grow old. Each of these women were once young and innocent, until they were sexually abused and essentially abandoned by their own families. One of them admits to being forced to have a child at age 12, while another tearfully tells tale of a childhood haunted by an endless repetition of rape. Later, this same woman, now homeless, is seen clutching her own newborn baby, joking with the locals that it might be their kin. Like many scenes that line this tragic narrative, it’s a bit hard to watch and yet we feel compelled to continue by the vibrant personalities and the pain they slowly reveal throughout the film.

As an aesthetically elementary, yet emotionally complex account of prostitution among the aged in a Mexican metropolis, Plaza de la Soledad speaks volumes on the contradictions implicit in the human heart and community acceptance. With the experiences these women have suffered through, one would expect each of them to have given up on the emotional intimacies of love and deep seeded need for the pleasures of tenderness, yet Goded’s attentive lens has been privy to an astoundingly resilient sense of solidarity among colleagues in a vicious profession. Reaching out with camera in hand, Goded offers these women a chance to show the world that being a prostitute doesn’t mean that after work they don’t need to be emotional support just like everyone else.

Reviewed on January 24th at the 2016 Sundance Film Festival – World Documentary Competition Program. 84 min

★★½/☆☆☆☆☆