Israeli vs. Israeli terrorist drama is a timely, thrilling provocation

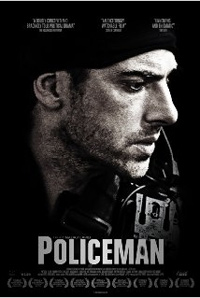

The opening scene of Israeli writer-director Nadav Lapid’s subversive, original terrorist drama Policeman is a precise snapshot of nationalistic delusion. A group of macho cops are pushing one another’s limits on a demanding bike training ride. They stop at a highway overlook for a breather. Lined up in a muscle-bound, spandex-ed row, they gaze out at an open landscape near Jerusalem: dullish brown, desiccated, dead. With prideful awe, the leader intones, “This is the most beautiful country in the world.”

The opening scene of Israeli writer-director Nadav Lapid’s subversive, original terrorist drama Policeman is a precise snapshot of nationalistic delusion. A group of macho cops are pushing one another’s limits on a demanding bike training ride. They stop at a highway overlook for a breather. Lined up in a muscle-bound, spandex-ed row, they gaze out at an open landscape near Jerusalem: dullish brown, desiccated, dead. With prideful awe, the leader intones, “This is the most beautiful country in the world.”

The leader is Yaron (Yiftach Klein is well-cast as a doer, not a thinker), one of the movie’s dual protagonists, a member of an elite Israeli counter-terrorist squad. The first half of Policeman takes an almost ethnographic approach to following Yaron’s daily life. At work, he hides in the backseat of a car and shoots an Arab insurgent point blank in the back of head; at home, he mechanically massages his pregnant wife’s shanks like a farmer would a heffer about to give birth. At play, he barbecues with his cop buddies, their compulsive bicep slaps and back poundings thundering on the soundtrack. With family, he initiates perfunctory religious ceremonies like the birthday hora — the raised chair dance — the way a personal trainer would demand reps from a lazy client.

Then, without warning, the movie shifts to its second protagonist: Shira (Yaara Pelzig resembles a younger, muted Jessica Chastain), a college-aged member of a radical revolutionary group, made up entirely of Israeli Jews, who are planning a major act of violence intended to shatter the status quo of Israeli society. Their complaints mainly have to do with class and economic disparities; “don’t bring the Palestinians in so soon,” is one of the feedback notes Shira gets from her compatriots for the latest draft of her evolving manifesto. Shira is not only under the dreamy spell of anarchist philosophy (what we hear of it is just a mishmash of familiar anti-authoritarian slogans), but also of the group’s blond pretty-boy leader. Will the group be able to carry out its daring plot? Or will one of the members chicken out, or worse, snitch to the authorities? Drawing out the answers to these questions, Lapid effectively uses a ticking-clock suspense mechanism to bring us toward a violent showdown between the two protagonists.

Policeman is one of the rare films to be critical of the Israeli state from the inside: Lapid is an Israeli Jew daring to boldly and broadly question the fundamental building blocks of Israeli society. The first-time feature director seems to have caught hold of something adrift in the socio-cultural winds: The movie was completed just before the recent high-profile mass protests in the Middle East, including the upheaval in Egypt, as well as social protests in Israel itself, over economic divides and real estate prices.

Israel’s history as a nation has been marked by the conspicuous lack of internal dissidence or social protest movements. This is perhaps due to the fact that the national consciousness has always been narrowly focused on external threats, the constant fixation on an outside menace. It’s also the result of a commonly accepted — and to some, oppressive — idea that all Jews are somehow obligated to be united together in the umbrella Zionist cause, regardless of their own individual political or philosophical beliefs.

The point being: Lapid has no real-life precedent to base his radical revolutionaries on, since no such group has ever existed in Israel. So instead, he had to invent them — and they are loonier, more fascinating and more disturbing because of it. They are revolutionary phantoms. Bourgeois and privileged, their comfortable idleness is their only qualification for considering violence; but the courage to take the manifesto out of their parents’ living rooms and into the real world can’t be ignored.

As pure invention, the presence of the revolutionaries in the movie exemplifies the imagination’s triumph against repression. Rebels didn’t exist, so Lapid imagined them; just as fascism is most powerful when its subjects internalize it and begin to self-police their own imaginations, so too the imagination can also serve as the greatest theater of resistance.

Lapid is far from taking sides. He is warily critical of both the cops’ and the radicals’ fetish for violence, guns, and detached, narcissistic ideologies. But there is simply no denying the exhilarating spirit of reckless revolt that suffuses the movie’s second half. The anarchic-destructive impulse is not so much nihilistic as it is a form of proto-creation, annihilation as a pre-condition for rebirth.

The viewer will struggle to resist a vicarious charge of frustrated anger — adolescent, sure, but genuine — when Shira growls at a billionaire’s privileged daughter, “You’re not a human being, you’re a bride!” It may be equally impossible not to feel a liberating rush of adrenaline when Shira declares to a stranger in a music club, with brazen coolness, “Tomorrow I’m going to change the order of creation. I’ve got a gun in my bag. Do you want to touch it?”

Reviewed on October 15th at the 2011 New York Film Festival