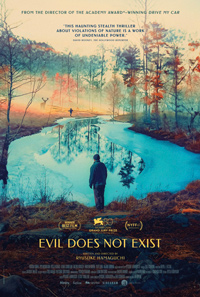

The Killing of a Sacred Dear: Hamaguchi Explores Ills of Urbanization

Ryūsuke Hamaguchi explores the doctrine about the absence of evil in his latest drama Evil Does Not Exist, a quiet film pondering the necessary evils of urban development and tourism on a small, Japanese village when a corporation aims to establish a glamping hotel in their midst. Like Mohammad Rasoulof’s 2020 Golden Bear Winner There Is No Evil, Hamaguchi’s overarching theme taps into the same ‘absence of good’ philosophy expounded upon from Nietzsche to Einstein, with roots reaching all the way back to Plato. In short, as this film also depicts, there are no innately evil people, only self-serving, ignorant humans who are, also, not inherently good. Originally intended as a short film for a collaboration with composer Eiko Ishibashi (Drive My Car, 2021), Hamaguchi’s latest bears the stretch marks of this unplanned expansion in the narrative, which sometimes struggles to seem cohesive in its parallel focus on the locals vs. the interlopers.

Ryūsuke Hamaguchi explores the doctrine about the absence of evil in his latest drama Evil Does Not Exist, a quiet film pondering the necessary evils of urban development and tourism on a small, Japanese village when a corporation aims to establish a glamping hotel in their midst. Like Mohammad Rasoulof’s 2020 Golden Bear Winner There Is No Evil, Hamaguchi’s overarching theme taps into the same ‘absence of good’ philosophy expounded upon from Nietzsche to Einstein, with roots reaching all the way back to Plato. In short, as this film also depicts, there are no innately evil people, only self-serving, ignorant humans who are, also, not inherently good. Originally intended as a short film for a collaboration with composer Eiko Ishibashi (Drive My Car, 2021), Hamaguchi’s latest bears the stretch marks of this unplanned expansion in the narrative, which sometimes struggles to seem cohesive in its parallel focus on the locals vs. the interlopers.

Takumi (Hitoshi Omika of Wheel of Fortune and Fantasy, 2021) lives alone with his young daughter Hana (Ryo Nishikawa) in the quiet, isolated Mizubiki Village. A beloved figure in an area developed by farmers and settlers who arrived in the region after the war, he’s a ‘jack-of-all-trades’ in the community, consumed by his own particular rhythm as a recent widower. The village denizens are suddenly alerted of a company based in nearby Tokyo planning to build a glamping (luxury camping) site up-river, not far from where Takumi lives. Takashasi (Ryuji Kosaka) and Mayuzumi (Ayaka Shibutani), who are talent scouts headhunted by the company to establish communication with the village, host a town hall, where community members point out all the adverse ripple effects the site’s ill planned design will have. Back in Tokyo, Takahashi and Mayuzumi are basically told they will have to superficially assuage the villagers but not make any actual structural changes to the plan, as doing so would delay construction and they’d lose out on lucrative subsidies, fast approaching an expiration date. In good faith, they return to Takumi’s home, suggesting he be employed as the site’s manager as a partial compromise. But the visit ends more disastrously than any of them could have anticipated.

We can’t see the forest for the trees in the night and day bookended frames of the film, as DP Yoshio Kitagawa’s (reuniting with Hamaguchi from his 2015 masterpiece, Happy Hour) camera gazes up into the heavens, as if answers are somehow expected to fall on our heads regarding the misery and conflict going on below. It’s interesting to compare this narrative to the five-hour Happy Hour, which, despite its running time, is utterly absorbing. In Evil Does Not Exist, there’s little by way of characterization, and we have to surmise a lot about Takumi and his daughter Hana, who seem to have lost their wife and mother sometime in the recent past. Takumi buries himself in his manual labor to the extent he’s often forgetting to pick Hana up from school, a little girl who’s already developed an innate sense of independence and exploration. In the film’s best scene, we are introduced to trials and travails of various community members during a Q+A session with the representatives of the corporation who’s descending upon them no matter they really have to say, an obvious rush job which seems blatantly unaware of the detrimental effects they’re about to impose on the village.

Where Evil Does Not Exist tends to lose interest is when the perspective switches to Takahashi and Mayuzumi, whose good intentions aren’t enough to overcome their ignorance. Takahashi suddenly appears as if he wants to move to the village and leave behind Tokyo in ways meant to create some levity before tragedy strikes. But its closing moments, meant to evoke the senseless and avoidable aspect of the scenario, feels leaden, forced. The sinister hints the script plants throughout are too overt, especially considering the subtleties surrounding a climax which weighs the film down like a manacle around its neck.

Reviewed on September 3rd at the 2023 Venice Film Festival – In Competition. 106 Mins.

★★½/☆☆☆☆☆