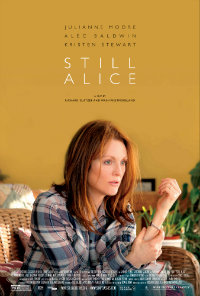

Red Queen’s Lost Her Head: Westmoreland & Glatzer’s Poetic Elegy of Familial Tragedy

It’s been a busy year for Julianne Moore, in between tent pole studio fare like the last Hunger Games installment and a Liam Neeson action flick she managed to snag Best Actress at the Cannes Film Festival for her perversely satisfying role in David Cronenberg’s Maps to the Stars. While that role is unlikely to generate the same amount of buzz from the Academy, it’s her moving performance in Still Alice that’s likely to garner her considerable awards attention and rightly so. The third film from Richard Glatzer and Wash Westmoreland, it’s a return to quiet, and subtle examinations of human interactions that so generously marked their breakout debut with 2004’s Quinceanera.

It’s been a busy year for Julianne Moore, in between tent pole studio fare like the last Hunger Games installment and a Liam Neeson action flick she managed to snag Best Actress at the Cannes Film Festival for her perversely satisfying role in David Cronenberg’s Maps to the Stars. While that role is unlikely to generate the same amount of buzz from the Academy, it’s her moving performance in Still Alice that’s likely to garner her considerable awards attention and rightly so. The third film from Richard Glatzer and Wash Westmoreland, it’s a return to quiet, and subtle examinations of human interactions that so generously marked their breakout debut with 2004’s Quinceanera.

A Columbia University Linguistics Professor, Alice Howland (Moore) has just turned fifty. Happily married to her husband, Dr. John Howland (Alec Baldwin), life seems rather fulfilling. They’ve three grown children, including their driven eldest daughter, Anna (Kate Bosworth) and son Tom (Hunter Parrish), while they have minor concerns about youngest daughter Lydia’s (Kristen Stewart) insistence on pursuing her dream of becoming an actor in Los Angeles. However, a series of growing memory lapses begins to alarm Alice, which leads to the discovery that she has Familial Alzheimer’s Disease, a rare form that strikes as early onset, prior to age sixty-five. Worse, she discovers that it’s been passed along to Anna. As time flies by, Alice’s faculties begin to deteriorate faster than expected, leaving her family to deal with the inevitability that soon, Alice won’t recall who any of them are.

For those that balked at Julie Christie’s Alzheimer’s diagnosis in Sarah Polley’s Away From Her (2006), Moore’s radiant and effervescent 50 year old Alice being struck down with the debilitating disease seems like nightmarish science fiction. But pains are taken to explain that her rare diagnosis of Familial Alzheimer’s Disease accounts for half the cases of early on-set Alzheimer’s, and is indeed a very real, if uncommon, possibility. Of course, Glatzer and Westmoreland instill a sense of heightened despair because Moore’s Alice is given so much to lose. A professor of linguistics and with a keen interest in the way humans communicate through language, it’s difficult not to empathize with the devastating loss generated. To their credit, Glatzer and Westmoreland avoid dipping the film into excessive bouts of melodrama, its fine supporting cast never over-emphasized.

As her supportive but distant husband, Alec Baldwin chooses to focus on life after Alice, along with their eldest daughter played by Kate Bosworth. The film instead chooses to explore Alice’s more complicated relationship with youngest daughter Lydia, in an understated performance from Kristen Stewart. As visible as Moore’s been in 2014, it’s been a surprising year for Stewart, popping up in a variety of excellent films in which she’s cast in roles clearly suited for her, including Camp X-Ray and Olivier Assayas’ excellent Clouds of Sils Maria. Those quick to judge may need to re-assess their opinion of the young star, as Still Alice caps a trio of provoking films that should all end up on year-end best lists.

Despite opening with a rather blatant dive into the material, what with Moore giving a speech and losing her train of thought, it provides a set-up for a much more powerfully rendered scene later on in the film. And just when it seems to be headed off into other obvious territories, Still Alice changes course, gently, naturally, and unobtrusively. It’s a remarkable showcase for Moore, and if you’ve been keeping up with her roles, a testament to her prowess as an actor. Both frustrating (as when she’s unable to carry through with a plan to circumvent years as an invalid) and incredibly moving, Still Alice is an examination of losing not only a loved one but the framework of one’s very being.

Reviewed on September 8th at the 2014 Toronto International Film Festival – Special Presentations Programme. 99 Minutes

★★★½/☆☆☆☆☆